Bleeding Baltimore: Mapping The City's Violent Crime & Searching For Solutions

BALTIMORE (WJZ) -- At least 113 people have been killed in Baltimore since the start of 2022, and the city is again on pace for more than 300 homicides.

Donna Taylor, who grew up in Southwest Baltimore, said she lives in fear. In a recent interview, Taylor told WJZ Investigator Mike Hellgren she no longer feels safe in the city she calls home.

"Not at all," Taylor said. "I'm so scared to walk anywhere. Bullets have no names. It makes me sick to my stomach knowing I have to go somewhere by myself."

She grew up in the Carrollton Ridge neighborhood, which has now seen at least 10 shootings and four murders this year, including the killing of her neighbor and friend, Charles Rheubottom.

"I was sitting in my chair and I heard the three gunshots," Taylor recalled. "We heard him take his last breath. I mean, it was so sad."

Rheubottom, a grandfather, collapsed March 9 next to a tree on South Smallwood Street. Almost two months later, his killing remains unsolved.

Taylor acknowledged that she might have provided Rheubottom with a small measure of comfort in his final moments.

"I think we did, but with the gunshots in his chest and all that blood, I knew he was gone," she said.

Taylor said she feels forgotten by Baltimore City leaders.

"The mayor…they don't care. The commissioner doesn't care. They can do more, but they just don't want to do more;" she said.

Asked if she had anything to say to Police Commissioner Michael Harrison and other city officials, Taylor had strong words.

"You need to do better," she said. "He's got to do better and so does Brandon Scott. What they're doing now is not working."

In a one-on-one interview, Hellgren asked Commissioner Harrison what he would say to citizens who do not feel safe in Baltimore.

"Look, we understand that, and we are working hard every single day," Harrison said. "The members of our department hit the streets every day to go out—number one—to prevent as much as we can."

The commissioner told WJZ that officers are targeting 81 micro zones across Baltimore, areas that see the most frequent violence.

"We focus on where officers should be, when they should be there and what they should be doing. High levels of community engagement, enforcement. It's all community policing and problem-solving policing, which we are teaching officers to do very differently than what we were teaching in years past," Harrison said.

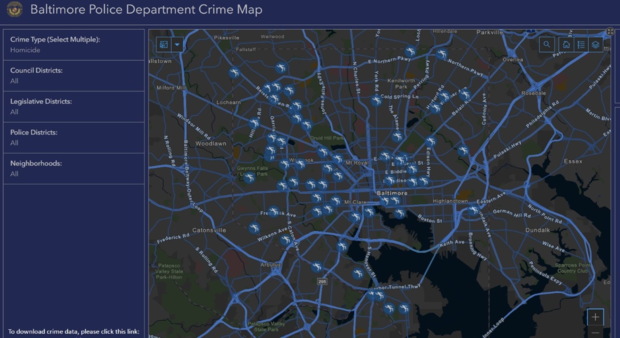

This year, shootings and homicides have unfolded throughout the city. (You can map them in your neighborhood using this tool.)

In the Edgewood neighborhood, five people have been killed in three separate shootings. They include Sophia Wilks, a mother of three gunned down in her home.

In Brooklyn, there have been more than 20 homicides and shootings, including Brittany Keyser, a mother of two.

In Upton, seven people have been shot.

Brazen acts have unfolded in Highlandtown, where WJZ was first to share video of a shootout.

A security camera captured another shooting that played out in front of a synagogue in Park Heights.

Bullets also went flying just a few blocks away from Johns Hopkins Hospital in East Baltimore.

Carjackings are up 65% year-to-date. One recent victim was a Johns Hopkins doctor who was on his way to work.

Convenience store robberies have skyrocketed, increasing by a whopping 394%.

"It's about consequences," Harrison said. "Lack of fear or lack of belief that the consequences even exist, and that's why you see such brazen acts of violence. In daylight. Shooting indiscriminately into crowds. One person hitting multiple people."

Asked if he would chalk up the notion about a lack of consequences to judges, prosecutors or something else entirely, the commissioner said "all of the above."

"It's all of the above," he said. "I have to make sure that my police department produces the best-quality criminal investigations and arrest cases that make it through the entire criminal justice system. And if there are reasons for it not to make it, it's not because we made some kind of error or some kind of mistake."

When asked whether there was truth to the narrative that the lack of prosecution for low-level drives up violent crime, the commissioner noted that not all low-level offenders graduate to violent crime.

"We know what triggers violent crime, and we know what pushes and pulls people towards violent crime. Trespassing, drinking from an open container, does not translate to someone committing a carjacking or maybe pulling the trigger all the time," he said.

"You can't put police in every single home, in every single corner. You have to change the culture that makes others make better decisions," he added.

Researchers at Johns Hopkins Center for Gun Violence Solutions found the areas with the most concentrated violence in Baltimore have something in common: neglect and a lack of economic investment.

"You're going to see a lot of disinvestment. You're going to see a lot of abandoned homes. You're going to see very few businesses," Dr. Daniel Webster, a health policy and management professor for the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and one of the nation's leading experts on firearm policy and gun violence prevention.

"It's a matter of reframing the way that we think about violence in our society. It's about thinking of it in more of a public health perspective," said Mudia Uzzi, a PhD candidate who has studied Baltimore violence. "It is investing in our communities. It is addressing issues around housing, around economic factors, around social cohesion."

"We know neighborhoods that have endured racist policies in the past like redlining and also currently experience economic and social deprivation now have some of the highest rates of violent crime," Uzzi added.

"If you look around you, and you can see the city frankly doesn't care about you and your neighborhood, that affects how you feel. That affects how you carry yourself. And the conflicts and the way you engage with people," Dr. Webster said. "…It's not just that one young parent who can't get their kid to school and get themselves to a job, it's a whole neighborhood with those kind of conditions and those kind of challenges and it is those conditions where people lose hope. They lose hope, and they're driven into underground economies where violence is how things are settled."

Part of the issue, Dr. Webster said, is that no one steps back to examine patterns between the number of shootings and the neighborhoods they afflict.

"We get fixated on police and prosecutors—but big picture, step back—what are the conditions going on in these communities in order not to have this repeating cycle of news every day and week?" he said. "We have to start changing these conditions."

RELATED: Baltimore Unveils Guaranteed Income Pilot Program | Community Members Meet Over Baltimore's Dangerous Vacant Properties | Mayor Scott Delivers 2nd State Of City Address

Commissioner Harrison told WJZ a big part of the city's strategy is addressing the root causes of violence: addiction, mental illness and poverty.

"We want to make sure that we are holistically looking at it," Harrison said. "Yeah, we want to stop it now, but we want to fix the original problem of why people make that bad decision to commit crime in the first place."

The commissioner boiled down the model of addressing crime to this: "we're going to help you if you let us, but we're going to stop you if you make us."

"It's all about root causes," the commissioner said. "You have to deal with the crime right now in its immediacy—preventing what we can prevent, apprehending people who commit crime—but it is also about changing the minds and changing the decisions of the offender. And the only way to do that is…through consequences and through helping them make better decisions. Stopping the violence right now for those we can reach…and helping those have a pathway away from crime."

Neighbors, like Taylor, are demanding action now, fearing they could be the next victim.

"It is a warzone here," she said.

Asked what it was like to experience the trauma of watching someone she knew well die in front of her, Taylor said the images of his final moment continue to haunt her to this day.

"It's something that doesn't leave your head because I still see it today," Taylor said. "I still see him lying there and him taking his breath. Scary. Because it could have me. It could have been one of my kids."