Attorneys: GPS Clears Man Of 2009 Baltimore Shooting

BALTIMORE (AP) -- Lamont Davis has a seemingly ironclad alibi for why he can't have been the triggerman in a Baltimore shooting that left a 5-year-old girl paralyzed. A GPS tracking device he'd been ordered to wear puts him in his home half a mile away at the time. Yet Davis sits in a Maryland prison serving life plus 30 years in the case, which was front page news in the city when it happened in 2009.

Davis' lawyers call what happened to him a failure of the system and a mindboggling miscarriage of justice, a case where the passion to punish someone trumped the technological evidence. And that's why they're asking Baltimore's top prosecutor to agree that his conviction should be set aside.

Davis, now 22, has some powerful allies. A state employee who is an expert on the GPS tracking system agrees he wasn't the shooter. So does the former head of the Department of Juvenile Services, which was responsible for the tracking device he was wearing. A forensic expert who recently re-examined surveillance footage of the shooter also cleared

Davis. All three have written letters supporting him.

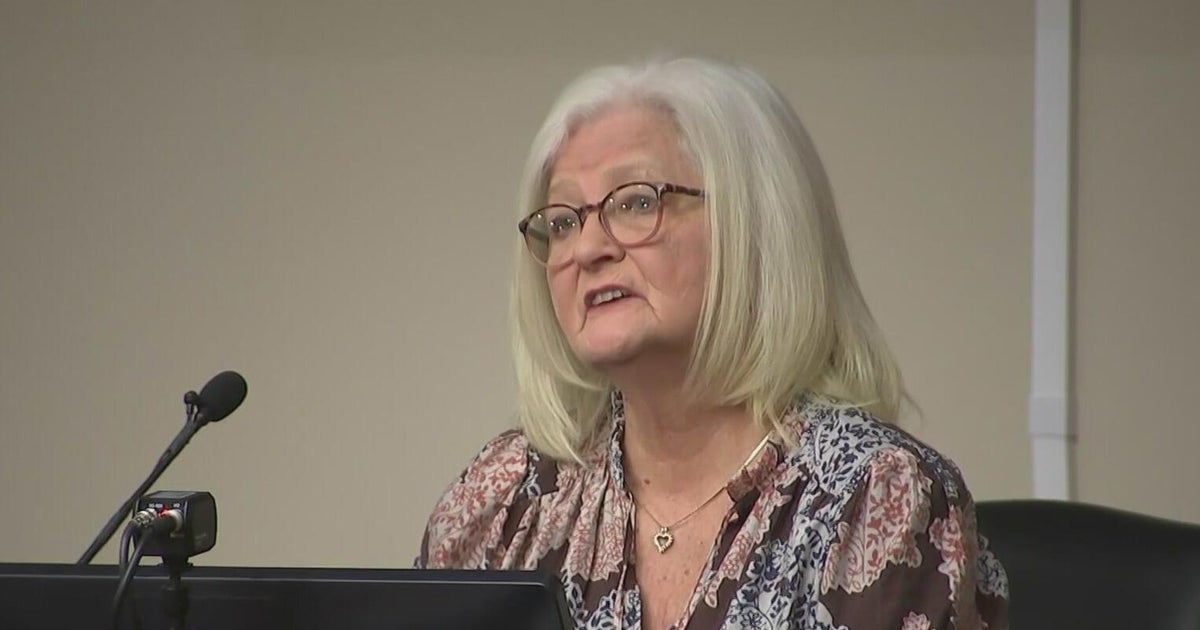

"Lamont Davis is serving a life sentence for a crime he didn't commit. That's the bottom line," said Michele Nethercott, one of Davis' lawyers and the head of the Innocence Project Clinic at the University of Baltimore School of Law.

The information from Davis' GPS anklet isn't new. It was part of his 2010 trial. But Nethercott says what the jury heard wrongly suggested the information was unreliable. And she called his former attorneys "ineffective," "disorganized" and "at times incoherent."

His former lead defense attorney, Linwood Hedgepeth, acknowledged in a telephone interview that he and his co-counsel made missteps. He said they improperly agreed Davis' GPS records showed he had violated his home detention 100 times, suggesting the GPS was worthless, when the real number of violations was closer to 10.

Now Nethercott, his new attorney, is asking Baltimore City State's Attorney Gregg L. Bernstein, who was not the city's top prosecutor when Davis' case was tried, to get involved.

Bernstein's office said in a statement that it is reviewing the case. Baltimore police referred all questions to the prosecutors.

The shooting that landed Davis in prison happened around 4 p.m. on July 2, 2009 at the corner of South Pulaski and Wilhelm streets, a residential area of mostly two story row houses. On that day, two teenagers, 15-year-old Dynaysha Hall and 17-year-old Tradon Hicks, argued on the street, according to Hall's trial testimony. She left angry and soon returned with a group of boys. A physical fight ensued and later someone fired shots.

Five-year-old Raven Wyatt was shot, and the image of her tiny pink flip-flops surrounded by crime tape helped fuel outrage.

Davis, then 17 and the father of two children with Hall, quickly became a suspect. Hall had been heard saying she was heading off to get him before returning with the group of boys. And two girls identified Davis as the shooter, though one said at trial she'd first picked out another person as the shooter from a photo array. Still, Davis' ankle monitor, which he'd been ordered to wear as a result of a juvenile record that is confidential, told a different story: when the shooting happened, he was home.

A police detective thought he had an explanation: Davis' monitor was recording all times on a 2-hour delay, meaning Davis could be the shooter.

Experts and Davis' lawyers say that's flat out wrong. So does Donald W. DeVore, the Department of Juvenile Services' head from 2007 to 2010. The system was accurately reporting times, and if he had any doubts about its reliability, the state wouldn't have renewed its contract for the tracking devices, he wrote in a letter supporting Davis.

"For reasons that are still not entirely clear to me somehow Lamont Davis was nonetheless convicted of attempted murder and given a life sentence for crimes that I am confident he could not have committed," DeVore wrote.

Davis also has the support of a forensic examiner his attorneys hired to review surveillance footage of the shooting. He concluded the grainy footage showed the shooter wasn't wearing an ankle bracelet. A Department of Juvenile Services expert on monitoring, Adrienne Simms, says photographic evidence showed Davis' bracelet had been securely attached to his leg, impossible to slip off. She too concluded he wasn't the shooter.

There has always been at least one other potential suspect, a boy nicknamed "Murder" who acknowledged during Davis' trial that he was part of the fight before the shooting.

Davis' attorney Michele Nethercott says her client wouldn't be the first to be misidentified by an eyewitness. And she said he isn't bitter but baffled by what happened and resigned to sitting in prison.

"The central, and really only, issue in this case was: where was he at the time of the shooting?" Nethercott said. "And the answer is he was at his house."