What you need to know about Zika virus

Concerns are growing over the mosquito-borne illness known as Zika virus, which has been spreading through Central and South America and is believed to be linked to a surge in serious birth defects in Brazil.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has issued a travel advisory urging pregnant women to avoid travel to more than 30 countries and territories, mostly in Latin America and the Caribbean, where Zika virus is present. Because of the possible link to birth defects, pregnant women who must travel to affected areas should talk to their doctor or other health care provider first and strictly follow steps to avoid mosquito bites during the trip, the CDC said.

The virus reached Mexico in November and Puerto Rico in December, and the CDC has confirmed more than 50 cases of Zika in the U.S., all but one in travelers who recently returned from trips to Latin America. In one case, a person who caught it abroad transmitted it to their partner through sex.

Here's a primer about what you should know about the disease.

What is Zika virus?

Zika virus is an illness transmitted to people through bites from mosquitoes of the Aedes species -- the same mosquitoes that spread dengue and chikungunya viruses. It not communicable from person to person but can be transmitted when a mosquito bites someone who's infected and then bites someone else.

The virus was first discovered in Uganda in 1947 and named after the forest in which it was found.

Officials say the current Zika outbreak in Brazil began last May. Authorities there estimate that since then, between 440,000 and 1.3 million people have caught it. Zika has spread to other countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, including Colombia, Venezuela, Honduras and Mexico. Puerto Rico reported its first case of locally transmitted Zika virus in December.

What are the symptoms?

According to the CDC, the most common symptoms of Zika virus are fever, rash, joint pain, and conjunctivitis. Other symptoms can include muscle pain, headache, pain behind the eyes, and vomiting.

Symptoms are usually mild, lasting from a few days to a week. Many people infected with the virus experience no symptoms at all. In rare cases, symptoms can become severe and require hospitalization.

A number of Zika patients in Brazil have also gone on to develop a rare autoimmune condition called Guillain-Barré syndrome, which can cause at least temporary paralysis. Health officials are investigating the possible connection.

Is there a vaccine or cure?

There is no vaccine to prevent Zika virus. The U.S. National Institutes of Health is ramping up efforts to develop one, but the process will take time.

"It is important to understand we will not have a widely available safe and effective Zika vaccine this year and probably not in the next few years," said Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the NIH's National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

There is no specific treatment for Zika except to try to ease the symptoms.

What do we know about its possible link to birth defects?

Health officials in Brazil say they've found strong evidence that Zika has been linked to a sudden rise in the number of babies being born with abnormally small heads, a condition called microcephaly, which often results in mental retardation.

Brazil's government reports more than 4,000 babies have been born with microcephaly since the Zika outbreak began there, up from fewer than 150 in 2014.

Dr. Peter Hotez, dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, explained how the connection was found.

"First we saw a dramatic rise in microcephaly in Brazil coinciding with when Zika was introduced there. This prompted an active search to see if there was a virus behind it and Zika was one of the suspect viruses, even though it was not shown previously to cause congenital birth defects," he told CBS News. "The researchers there took blood samples and other tissue samples from these babies with microcephaly and found evidence of the virus in the samples. They also sampled the amniotic fluid of mothers who had babies with microcephaly and that really helped confirm the connection."

While more research is needed to confirm true cause and effect, and experts acknowledge other factors may be at play, researchers say the evidence to support the link is strong. In response, authorities in Brazil, El Salvador and some other affected areas have told women to put off pregnancy if they can.

I'm traveling to an affected region. Should I be concerned?

Currently, the CDC recommends that all travelers to areas where Zika is spreading -- mostly in South America, Central America, the Caribbean -- take steps to protect themselves from mosquitoes.

"Out of an abundance of caution," the CDC said it's advising pregnant women in any trimester to avoid travel to areas where Zika is spreading, if possible, or to take extra precautions to avoid mosquito bites if they must be there. Women trying to become pregnant or who are thinking about becoming pregnant should consult with their health care provider before traveling to these areas and take care to protect themselves from mosquito bites.

The countries named in the CDC travel alert include:

- In Latin America: Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, El Salvador, French Guiana, Guatemala, Guyana, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Suriname and Venezuela.

- In the Caribbean: Aruba, Barbados, Bonaire, Curacao, the Dominican Republic, Guadeloupe, Haiti, Jamaica, Martinique, St. Martin, Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands.

- Cape Verde, off the coast of western Africa.

- American Samoa, Samoa and Tonga in the South Pacific.

A complete list can be found on the CDC's website.

"The reality is we don't have a vaccine so it is very reasonable to inform the public that there is a real risk there," Dr. Trish Perl, senior epidemiologist and professor of medicine in the division of infectious diseases at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, told CBS News. "I don't know if we're going to be able to delay all travel but I'm not sure right now is the time to send someone who's pregnant to the Amazon for a vacation. You'd probably want to wait on that. Especially with pregnancy, we do err with being more cautious until there's further data."

What can I do to protect myself?

The CDC recommends the following steps to avoid mosquito bites:

- Cover exposed skin by wearing long-sleeved shirts and long pants.

- Use an insect repellent approved by the Environmental Protection Agency as directed.

- Higher percentages of active ingredients provide longer protection. Use products with the following active ingredients: DEET, Picaridin, oil of lemon eucalyptus (OLE), IR3535.

- Use permethrin-treated clothing and gear, such as boots, pants, socks, and tents. You can buy pre-treated clothing and gear or treat them yourself.

- Stay and sleep in screened-in or air-conditioned rooms.

- Use a bed net if the area where you are sleeping is exposed to the outdoors.

A few cases of sexual transmission have been documented, so the CDC also advises pregnant women and their partners to abstain from sex or use condoms if the partner has traveled to an area where Zika is spreading.

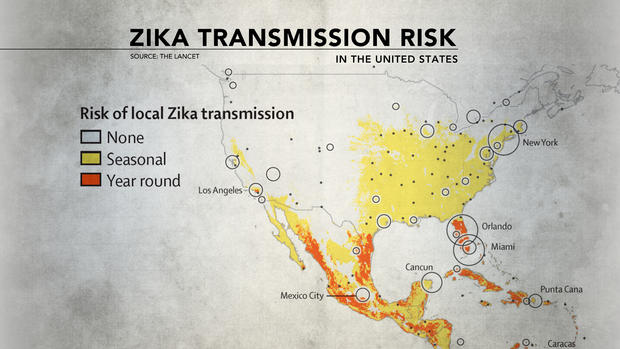

Will Zika virus become a problem in the U.S.?

So far several dozen travelers infected abroad have been diagnosed with Zika in the U.S., and experts believe it is inevitable that we will see more cases in this country.

"The mosquitoes are here," Hotez said. "They're certainly not as abundant in the winter months as they are in the spring, but there are probably a fair number of people here who have visited the Caribbean or Latin America who are already infected with Zika virus. Our mosquitoes are going to bite those individuals, pick up the virus, and transmit it to another person."

Florida governor Rick Scott declared a state of emergency in four counties with Zika cases February 3, authorizing more spraying against mosquitoes and other measures to control its spread.

Hotez said immediate action is necessary to minimize the harmful effects of Zika virus.

"We're seeing rapid spread of the virus and we need to act now," he said. "The first thing is to undertake a program of active surveillance throughout the Western Hemisphere, not only where it is right now but in places it could soon rise, including the Caribbean and the Gulf Coast of the U.S. Then if we start seeing transmission in these areas, provide appropriate advisories and education materials to women of reproductive age who are pregnant or are planning on getting pregnant."