What happened when Texas tried to replace Planned Parenthood

AUSTIN, Texas -- In pushing a replacement for the Affordable Care Act that cuts off funds for Planned Parenthood, Republicans are out to reassure women who rely on the major health care organization that other clinics will step up to provide their low-cost breast exams, contraception and cancer screenings.

Texas is already trying to prove it. But one big bet is quietly sputtering, and in danger of teaching the opposite lesson conservatives are after.

Last summer, Texas gave $1.6 million to an anti-abortion organization called the Heidi Group to help strengthen small clinics that specialize in women’s health like Planned Parenthood but don’t offer abortions. The goal was to help the clinics boost their patient rolls and show there would be no gap in services if the nation’s largest abortion provider had to scale back.

The effort offered a model other conservative states could follow if Republicans make their long-sought dream of defunding Planned Parenthood a reality under President Donald Trump. Several states are already moving to curtail the organization’s funds.

But eight months later, the Heidi Group has little to show for its work. An Associated Press review found the nonprofit has done little of the outreach it promised, such as helping clinics promote their services on Facebook, or airing public service announcements. It hasn’t made good on plans to establish a 1-800 number to help women find providers or ensure that all clinics have updated websites.

Neither the group nor state officials would say how many patients have been served so far by the private clinics.

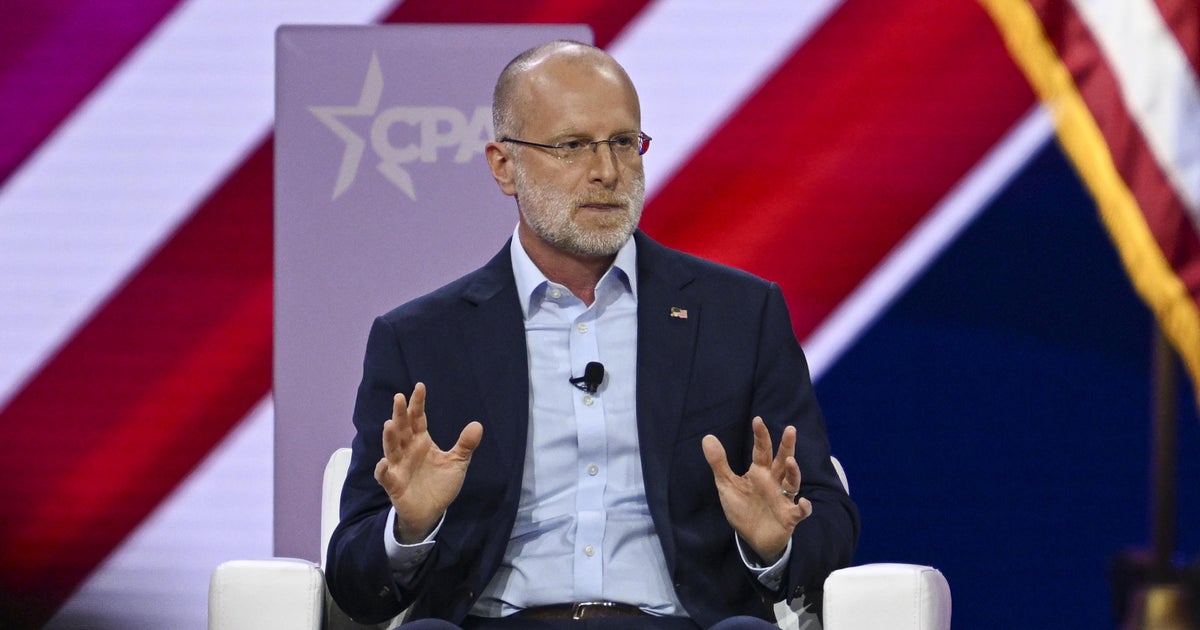

The Heidi Group is led by Carol Everett, a prominent anti-abortion activist and influential conservative force in the Texas Legislature.

In a brief interview, Everett said some of the community clinics aren’t cooperating despite her best efforts to attract more clients.

“We worked on one Facebook site for three months and they didn’t want to do it. And we worked on websites and they didn’t want to do it,” Everett said of the clinics. “We can’t force them. We’re not forcing them.”

Everett said that advertising she planned was stalled by delays in a separate $5.1 million family planning contract.

Everett proposed helping two dozen selected clinics serve 50,000 women overall in a year, more than such small facilities would normally handle. Clinic officials contacted by the AP either did not return phone calls or would not speak on the record.

The Texas Health and Human Services Commission, which awarded the funding to the Heidi Group, acknowledged the problems. Spokeswoman Carrie Williams said in an email that the agency had to provide “quite a bit” of technical support for the effort and make many site visits. She disputed that the contract funding has been as slow as Everett alleged.

“The bottom line is that we are holding our contractors accountable, and will do everything we can to help them make themselves successful,” she said.

In August, the state had lauded Everett’s pitch for taxpayer funds as “one of the most robust” received.

Planned Parenthood and its supporters say the failures show the risks of relying on unproven providers to serve low-income women, and that Republicans’ assurances about adequate care are only political rhetoric.

“Every time they try to relaunch one of these women’s health programs, without some of the most trusted providers in women’s health, every single time they come up short,” said Sarah Wheat, a Planned Parenthood spokeswoman in Texas. “And they show their lack of understanding and respect for what women need.”

On Tuesday, the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office estimated that 15 percent of low-income people in rural or underserved areas would lose access to care if Planned Parenthood loses funding. The analysis also projected several thousand more births in the Medicaid program in the next year.

The Heidi Group is an evangelical nonprofit that started in the 1990s and is best known for promoting alternatives to abortion. It operates with a relatively small budget, taking in about $186,000 in grants and donations in 2015, according to tax records, and had not been doing patient care.

State officials say the year-old women’s health program includes about 5,000 providers. Planned Parenthood and other abortion providers are banned from participation.

Federal dollars comprise nearly half of the Planned Parenthood’s annual billion-dollar budget, and although government funds don’t pay for abortions, the organization is reimbursed by Medicaid for non-abortion services that it says the vast majority of clients receive. Missouri is planning to reject federal funding just to keep some of it away from Planned Parenthood, and Iowa is also considering giving up millions in federal Medicaid dollars to create a state-run family planning program that excludes abortion providers.

U.S. House Republicans’ health care bill would freeze funding to Planned Parenthood for one year. House Speaker Paul Ryan has suggested other clinics will pick up the slack.

“It ends funding to Planned Parenthood and sends money to community centers,” Ryan said last week.

Democrats argue that other clinics are already overloaded and wouldn’t be able to meet increased demand.

After Texas state funding was cut off to abortion providers in 2011, 82 family planning clinics closed in the state, a third of which were Planned Parenthood affiliates. A state report later found that 30,000 fewer women were served through a Texas women’s health program after the changes. Planned Parenthood now has 35 clinics in Texas and served more than 126,000 individual patients last year, including those seeking abortions. The state has provided no estimates of low-income women served by other clinics.

Asked whether the Heidi Group would meet the patient targets in her contract, Everett said her own goal was to serve 70,000 women.

However, “it’s not as easy as it looks because we are not Planned Parenthood. We are working with private physicians and providers,” Everett said after leaving a committee hearing this week at the Texas Capitol. She said the clinics she is working with are busy seeing 40 to 50 women a day. “They don’t have time to go out and do some of the things that we would really like to help them do. But we’re there if they want to. And we’re there when they need it. And we’re in their offices and we’re helping them.”

She had been at the Capitol to support a bill that would require abortion clinics to bury or cremate fetal remains.