Water streaming across Antarctica surprises, worries scientists

In a unique study spanning the entire continent, scientists have found that water is gushing across Antarctica — more than they ever realized.

The researchers from Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory have found significant drainage of meltwater flowing across the continent’s ice sheets during summer in Antarctica. Until now, these streams of water were mainly associated only with Antarctica’s far north regions.

The discovery of widespread streams across the continent is ominous news, indicating Antarctica’s ice may be much more vulnerable to melting than scientists predicted. Free-flowing water, which absorbs solar energy more than ice, puts nearby ice at greater risk of melting.

“I think most polar scientists have considered water moving across the surface of Antarctica to be extremely rare. But we found a lot of it, over very large areas,” Jonathan Kingslake, a glaciologist at Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory and lead author of the study, said in a statement.

“This is not in the future — this is widespread now, and has been for decades,” he said. The research was published this week in the journal Nature.

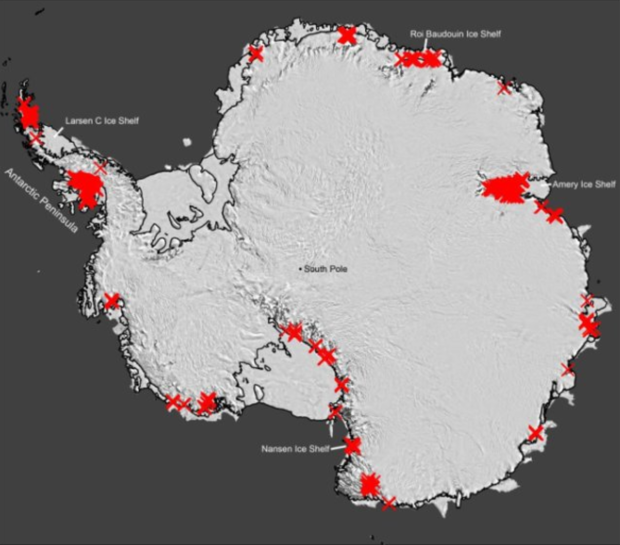

In the study, climate scientists carefully catalogued aerial and satellite images of Antarctica from 1947 to the present. The images helped them map 700 distinct systems of ponds, channels and streams across the continent, researchers said. They noted that there’s no clear evidence to suggest the number of meltwater drainages has increased over the time period they covered. But, this study provides a baseline for evaluating the spread of free-flowing water across the continent in the future.

The meltwater appears to proliferate whenever Antarctica’s temperature creeps up, researchers said, a bad omen as the continent is expected to plunge deeper into global warming this century.

Antarctica stands on the front lines of global warming, as rising temperature have wreaked havoc on the icy continent. Recent years have also transformed the Arctic, with significantly warmer temperatures, lower levels of sea ice, and more open water.

Experts say Arctic warming creates a toxic feedback loop: as the Arctic continues to warm, it will release greater levels of the greenhouse gas methane, formerly locked in the frost, which in turn absorbs the sun’s heat and further accelerates the warming of the planet. Last year, 2016, was the warmest year on record since official record keeping began in 1880, according to analyses from NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

The below video captures a meltwater stream flowing from Antarctica’s Nansen Ice Shelf into the ocean:

“These streams are something that require more investigation,” said Paul Mayewski, director of the Climate Change Institute at the University of Maine and a climatologist who’s done significant fieldwork in Antarctica. Mayewski was not involved in the study but called it “impressive.”

What are the stakes? As meltwater drains across Antarctica, it flows into the crevices of the so-called “ice shelves” that surround the continent, weakening those ice structures from within. Over time, free-flowing water could lead Antarctica’s ice shelves to collapse entirely, triggering dangerous sea level rise across the world.

The Columbia University researchers expanded on these consequences in an accompanying study, also published in Nature.

Sea level rise is expected to pose a massive threat to humankind this century. Global sea levels could rise between one foot and 8.2 feet by the year 2100, according to projections published by NOAA earlier this year. Though eight feet may not sound like a huge number, the consequences to human life would be devastating, as would the economic impact: researchers estimate that a rise of just six feet would be enough swallow up the homes of about six million Americans.

For Mayewski, the new study is as a warning: that Antarctica’s ice sheets are more precarious than long thought.

“Cities preparing for a conservative view of sea level rise by 2100 may be underestimating the full potential,” he said.