War and Hunger

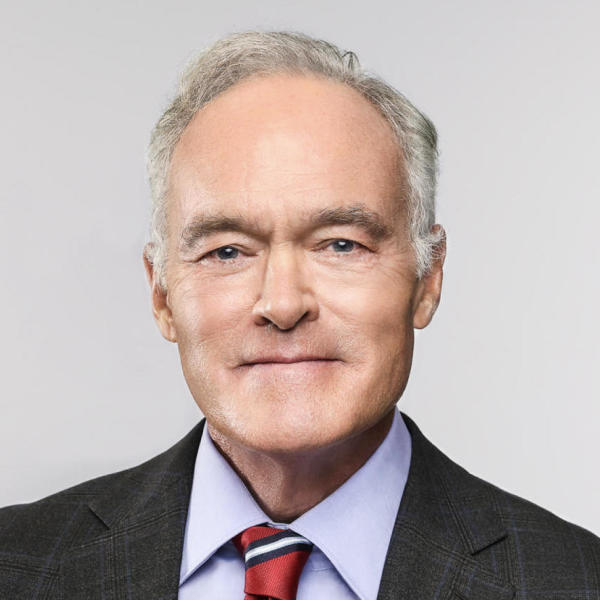

The following is a script of "War and Hunger" which aired on November 30, 2014, and was rebroadcast on August 9, 2015. Scott Pelley is the correspondent. Nicole Young and Katie Kerbstat, producers.

The World Food Programme might be just one of the best ideas America ever had -- WFP is the emergency first responder to hunger anywhere on the globe. The United Nations launched WFP in 1961 at the urging of the United States. And today the U.S. government still pays the biggest part of the bill as the World Food Programme feeds 80 million people a year.

We first brought you this story in November as WFP faced its greatest challenge, confronting war and hunger. And that's what's happening still today in Syria where you will find heroes of the World Food Programme saving the most vulnerable people in what looked to us like the edge of oblivion.

The map said, "No Man's Land." Last summer, we plowed the border of Jordan and Syria where the Jordanian military told us we would find refugees. But considering the wasteland it seemed more likely the map was right -- who could survive here?

But after several hours we found them, pouring over the land like a flash flood. With three hundred miles behind them, these Syrian families made their final steps through a war that nearly killed them and a desert that could have finished the job. Watch a moment and listen.

Scott Pelley: This berm marks the border between Syria and Jordan. The refugees that we ran into were coming across the top of the berm and turning themselves in to the safety of Jordanian border officers here. More than a million have crossed into Jordan so far during the three-year civil war in Syria.

They had been farmers, shopkeepers, office workers. Now they shared one occupation: saving the children with matted hair and faces covered in ten days of misery. We noticed the little ones around Halima. Turns out she's the mother of nine.

Scott Pelley: Why did you come?

"There's bombing all around us," she said, "I'm afraid for my children. But I don't know what will become of us now."

Scott Pelley: You don't know what's coming next but you know this must be better than where you came from?

She had taken five of her children. Her husband took four by another route. And they hope to find one another. Halima said they managed to save everyone in her family. But as for the fate of others in her town -- no translation was needed.

Andrew Harper: This is happening every day. Every day we are getting hundreds of people, sometimes up to a thousand people, fleeing the violence, fleeing the deprivation in Syria and coming across into Jordan.

Andrew Harper is in charge in Jordan for the United Nations high commissioner for refugees.

Scott Pelley: What kind of shape are they in when they come at the end of this journey?

Andrew Harper: It's horrific. We're seeing children coming across now without any shoes. Often they've only got one pair of clothes, some of them are just wearing their pajamas because, when their places were bombed, they had nothing to grab to leave.

"Are we willing to lose a generation of children to hunger?"

The U.N. refugee relief agency and Jordanian troops met the families, gave them food and water, and loaded them up for the trip to a U.N. camp. There was room for everyone on the trucks but no mother would take that chance. They pressed their children in first. Parents had sacrificed all they had to see this moment. And a long dead emotion began to stir. It felt like hope.

Scott Pelley: You know, this war's been going on for three years. Why are these people still coming now?

Andrew Harper: Because it's getting worse. I think now more than ever there is absolutely no hope for the future at the moment in Syria.

Part of what has stolen hope inside Syria is hunger. Starvation is a weapon in the war that began as an uprising against the dictator Bashar al Assad. These words read, "kneel or starve." Signed Assad's soldiers. All sides are laying siege to communities and cutting off the food. This is what happened in a neighborhood called Yarmouk in January of 2014 when a U.N. food convoy broke through. The people had eaten the dogs and the cats and were running low on leaves and grass. This girl eventually starved to death, five miles or so from a supermarket.

Ertharin Cousin: Are we willing to lose a generation of children to hunger? To lack of access to medicines? To lack of access to water while we wait until the fighting stops? No. We can't.

Ertharin Cousin is executive director of the World Food Programme. She's a former food industry executive from Chicago. WFP is often headed by an American because the U.S. donates more than a third of the four billion dollar annual budget.

Ertharin Cousin: The operation in Syria is one of the largest that we have ever operated in WFP. We have over 3,000 trucks supporting 45,000 metric tons of food delivered every month inside Syria.

Scott Pelley: All of that and your people are getting shot at.

Ertharin Cousin: All of that and people are getting shot at. It's a war zone. It's a conflict zone. The world doesn't stop. The war doesn't stop. The conflict doesn't end because people need to eat.

The World Food Programme estimates that more than six million Syrians do not know where their next meal is coming from.

Matthew Hollingworth: These are areas where people have nothing. They really do have nothing.

Matthew Hollingworth heads the World Food Programme mission inside Syria. In February of 2014, he led an armored column into the city of Homs, which had been sealed off by the dictatorship for 600 days.

Matthew Hollingworth: People were skin and bones. I could lift a grown man because he'd got to about 40 kilos.

Scott Pelley: 85 pounds or so?

Matthew Hollingworth: Exactly.

In the city of Homs, months of negotiations had opened a three-day ceasefire to distribute food. But it turned out the starving residents wanted something else first.

Matthew Hollingworth: The people of Old Homs asked us to evacuate women, children and the sick before any assistance came in. So we went through the last checkpoint. And there we could see in front of us 80 or 90 children, women and sick and injured people waiting to come out. And then the worst thing happened. The sniping started.

Scott Pelley: People were shooting at you.

Matthew Hollingworth: People started to shoot at us. So we took the decision then to put the vehicles, the armored vehicles in front of the area where they were shooting down in the alley to allow the people to come out. It was a hugely moving experience. And we successfully brought them out. This opened the way the following day for us to go into Homs and deliver the first assistance and we did that successfully, but halfway through, sadly, the operation, we came under mortar fire.

Matthew Hollingworth: It was panic, chaos. People screaming, people running everywhere. The hot metal flying around you.

Scott Pelley: You decided to stay. And I wonder why.

Matthew Hollingworth: We'd seen the faces of the people who were asking us to help them, asking United Nations to help them in their time of crisis, which is why we're here. So we again negotiated with all the sides to this time obey the ceasefire, to respect the ceasefire. And we went in the following day and the next day and the next day, and the rest is history.

"Nobody in this world, no matter who he is, deserves to die from hunger."

History records that in Homs, WFP evacuated 1,300 people and brought in enough food to feed 2,500 others for a month. But elsewhere in Syria more than one million remain beyond reach.

[Man in YouTube video: November the fifth 2013...]

We know they're there because we can hear their pleas for help. Kassem Eid, from the Damascus suburb called Moadamiyeh, put out a series of videos on YouTube.

[Kassem Eid in YouTube video: In a protest to the world to enter the humanitarian aids to the besieged city of Moadamiyeh.]

After several videos begged for someone to break the siege, Eid made his way out of Syria.

[Kassem Eid in YouTube video: People are starving to death while food and medicine is only two minutes away behind the Assad checkpoints.]

Scott Pelley: Tell me what you witnessed, what you saw with your own eyes.

Kassem Eid: Even while the regime is bombing, nobody cared. It seems like if you die from the shelling, it will be a merciful way to die instead of dying from hunger because it will take months to die from hunger. People lost faith with the world, with their families, even with God. Nobody understood that we can die from hunger in the 21st century in Syria.

Scott Pelley: The regime shelled Moadamiyeh to rubble, used nerve gas on the population, but it was starvation...

Kassem Eid: Yes.

Scott Pelley: ...that broke the town.

Kassem Eid: That's absolutely true. It can destroy your soul, your mind, your beliefs, before it can destroy your body. Nobody in this world, no matter who he is, deserves to die from hunger. Nobody.

That is the principle on which the World Food Programme was founded, an idea in the Eisenhower administration, after 70 million people around the world starved to death in the first half of the 20th century. Today, WFP is in 75 countries plagued by war or weather. It has an air force, a navy and an army of 14,000 people.

But emergency response is just part of what it does. The World Food Programme prevents famines by teaching farming. It uses its vast purchasing power to support small farms. All of this despite the fact that WFP gets no funding from the United Nations. It raises its budget entirely from donations by governments, companies and individuals. But in Syria the need is so great, the money is falling short. We got a sense of the scale of that need by flying over the latest U.N. refugee camp with the Jordanian police and the U.N.'s Andrew Harper.

Andrew Harper: We're looking at probably one of the world's largest refugee camps.

The refugee families we saw earlier at the border were headed here.

Scott Pelley: You have built this for 130,000 refugees. Do you think you're going to have that many?

Andrew Harper: Well if you look it there's about six and a half million people displaced in Syria. I think we may even need to build more than this.

When the U.N. camps opened, the World Food Programme served three meals a day. But it soon discovered that these families hungered for more than just a meal.

Ertharin Cousin: What they're receiving is not food. But they're actually receiving a voucher, which will give them the ability to decide what food their family can eat for the month.

Scott Pelley: Why do you do that?

Ertharin Cousin: It gives them a choice, more than anything else and it gives them respect.

Respect because the vouchers are a ticket here. Where there was only desert, the World Food Programme has built supermarkets like any in America. Osama and his wife led nine children through the desert after their daughter was wounded by a mortar. Each member of his family now gets a WFP voucher for 29 dollars a month.

Scott Pelley: The difference between being fed out of the back of a truck and cooking your own meal is dignity.

Ertharin Cousin: It's dignity. It's providing your children with some hope.

Back on the border, in the last moments of the day, we ran into another exodus, families pressing through no man's land on a path marked only by the desperate steps of those who'd come before. Jordanian troops crossed into Syria to lift a woman who had stopped short saying, "Mother we are on the border."

Over the summer, Jordan severely restricted the numbers it would accept on its borders. And, the World Food Programme was forced to cut back its rations for lack of funds. But millions more are on the move and the days of war remain uncounted.