Utility understated levels of cancer-causing chemical from gas leak

LOS ANGELES -- The utility whose leaking natural gas well has driven thousands of Los Angeles residents from their homes acknowledged Thursday that it understated the number of times airborne levels of the cancer-causing chemical benzene have spiked during the crisis.

Southern California Gas Co. had been saying on its website and in emails to The Associated Press that just two air samples over the past three months showed elevated concentrations of the compound. But after the AP inquired about discrepancies in the data, SoCalGas admitted higher-than-normal readings had been found at least 14 times.

SoCalGas spokeswoman Kristine Lloyd said it was "an oversight" that was being corrected. The utility continued to assert that the leak has posed no long-term risk to the public.

The company was given repeated opportunities to explain its conclusions but couldn't, CBS Los Angeles reported.

"I don't know what would explain it," spokeswoman Melissa Bailey told the station.

Public health officials have likewise said they do not expect any long-term health problems. But some outside experts insist the data is too thin to say that with any certainty. For one thing, it is unclear whether the benzene fumes persisted long enough to exceed state exposure limits.

"I have not seen anything convincing that it's been proven to be safe," said Seth Shonkoff, the executive director of an independent energy science and policy institute and a visiting scholar at the University of California, Berkeley. "I'm not going on record as saying this is absolutely an unsafe situation; I'm saying there are a number of red flags."

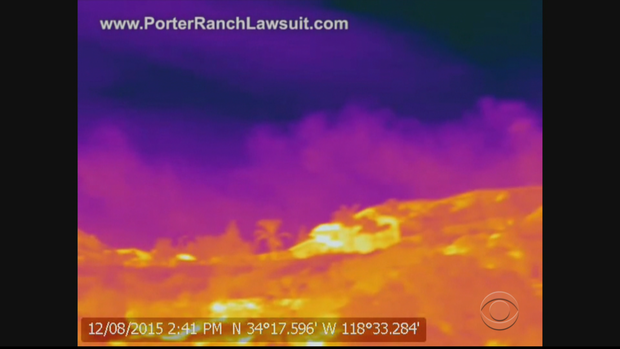

The leak at the biggest natural gas storage facility west of the Mississippi River was reported Oct. 23. The cause is unknown, but the leak has spewed huge amounts of methane, a potent greenhouse gas, and occasionally blanketed neighborhoods about a mile away with a sickening rotten-egg odor.

On Monday, state lawmakers called for parts of the Aliso Canyon storage facility to be shut down until state officials and an outside agency can verify that they do not pose a risk to public health, CBS Los Angeles reported. People who live nearby also want the facility closed.

SoCalGas has run up more than $50 million in costs so far in trying to contain the leak and relocate about 4,500 families. Gov. Jerry Brown has declared an emergency, and some environmentalists are calling it the worst environmental disaster since the BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico in 2010.

Health officials and SoCalGas have said most of the gas has dissipated, though the odor from the chemical additive that makes the methane detectable is blamed for nausea, headaches and nosebleeds.

Natural gas also contains smaller amounts of other compounds, such as benzene, that cause cancer as well as anemia and other blood disorders.

In the Los Angeles area, benzene is normally present at minuscule levels of 0.1 to 0.5 parts per billion, according to the South Coast Air Quality Management District. But SoCalGas has been saying on its website that the typical background level is 2 parts per billion.

Apparently relying on that standard, SoCalGas originally said that benzene was found in amounts slightly higher than background levels in just two samples, both on Nov. 10. The suspect readings were 5.6 parts per billion in one gated development about a mile from the well and 3.7 parts per billion in the Porter Ranch Estates neighborhood of 1,100 homes.

However, a more detailed look at the data by the AP and outside experts showed at least 10 other instances over seven days in November when benzene exceeded 1 part per billion.

In its update Thursday, SoCalGas said that nearly 1,200 tests had found 14 instances where benzene exceeded 1 part per billion, including one time in December.

The World Health Organization and U.S. government classify benzene as an undisputed cause of leukemia and other cancers. "No safe level of exposure can be recommended," according to WHO.

California's Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment in 2014 set a series of limits for the amount of benzene people could be exposed to without risking anemia and other noncancerous disorders.

Those limits are 8 parts per billion for a one-time exposure, 1 part per billion for repeated exposures for eight hours at a stretch, and 1 part per billion for several years or a lifetime.

Michael Jerrett, chairman of the environmental health department at the University of California, Los Angeles, said that because of the limited testing done by SoCalGas early on, it is impossible to know for sure whether there was repeated exposure in parts of the community. He said he believes there is a "high probability" the eight-hour standard was violated.

One problem with the testing is that it was done over very short periods that can indicate spikes but can't provide meaningful data on long-term exposure.

Dr. Cyrus Rangan, a medical toxicologist from the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health, said it is unlikely state safety levels were exceeded because spot testing didn't turn up a larger, more consistent pattern of high readings.

"You can't take a 10-minute sample that's 5.6 parts per billion and make any long-term risk assessment," Rangan said. "If that was sustained over several months in a row, I'd be concerned about that, but we know that's not happening."

More comprehensive testing is underway, though the amount of gas being released has dropped about 60 percent as pressure in the well drops.

Since Dec. 21, the air district has been taking samples around the clock, and all but one showed benzene at 0.1 parts per billion, said spokesman Sam Atwood. One sample was 0.2 parts per billion.