Tortured at Guantanamo, former inmate finds forgiveness

Mohamedou Slahi says his first few years at Guantanamo Bay were rough. He was interrogated for 70 straight days, almost around the clock. He says he was dragged from his cell, put on a boat, and forced to drink salt water until he choked. His uniform was packed with ice until he shook uncontrollably from the cold. Then, he says, he was beaten.

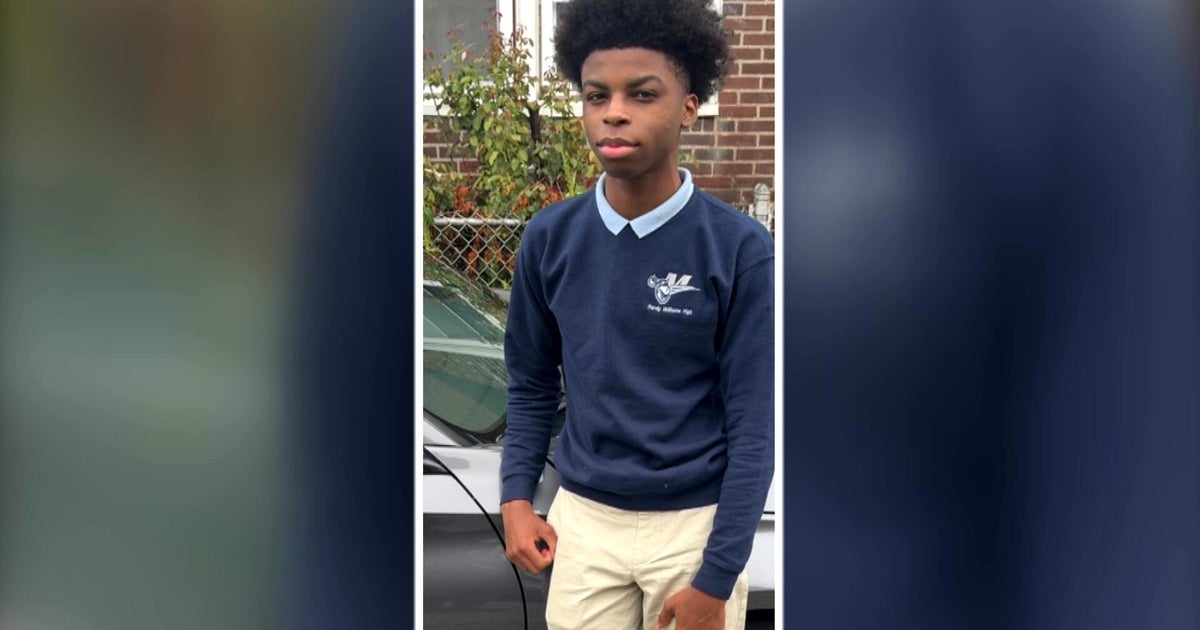

This week on 60 Minutes, correspondent Holly Williams speaks with Slahi at his home in Mauritania, where he returned after being released in October. He spent 14 years behind bars in Gitmo, though the United States never charged him with a crime, and he has maintained he never had anything to do with terrorism.

Slahi now says he isn't resentful.

"Anger is very painful in the heart," he tells Williams in the video above. "So why should I be angry? Why should I pay twice?"

Williams tells 60 Minutes Overtime's Ann Silvio that she thinks Slahi's forgiveness is genuine. Americans may have imprisoned and tortured him — but Americans also aided him in getting released from Guantanamo, and in editing and publishing a book about his experience, called Guantánamo Diary. Released while Slahi was still a prisoner, the book has now been translated into 27 languages.

"He understand that he was helped enormously by American people as well," Williams says. "So I think that has helped him come to a position where of course he doesn't hate American people."

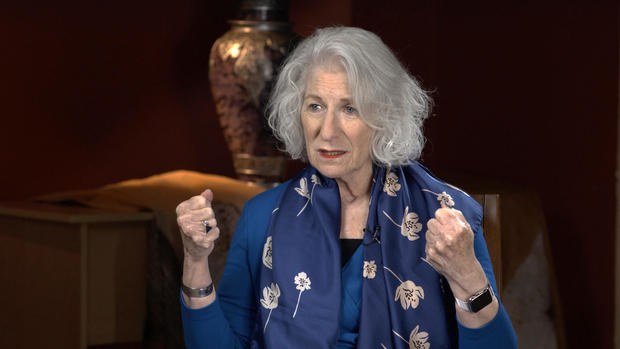

Lawyer Nancy Hollander is one of the Americans who fought for Slahi's release. She says his case was different from any case she'd worked on — and that Slahi was different from any client she's had.

"Mohamedou is much more than just a client to me," she says. "After 11 years and many, many hours together, many meals together, letters back and forth, we really have become friends."

"Anger is very painful in the heart. So why should I be angry? Why should I pay twice?" Mohamedou Slahi

Larry Siems was the editor of Slahi's book. He says Slahi — who learned English while being held at Guantanamo Bay — wrote his way out of prison.

"[He is] a man who believed in the power of words and the power of literature to convey the truth, to change people's minds," Siems says in the video above. "He believed that if we just read his story, encountered his story, that we would make the right decision."

Slahi's story began in the early 1990s, when he traveled to Afghanistan to fight the Soviet Union-backed Communists. The mujahideen, as the fighters were known, were armed by the United States.

Slahi says he later joined al Qaeda but then severed his ties to the group, and denies ever having anything to do with terrorism. His cousin, however, was a close spiritual advisor to Osama bin Laden. When that cousin called him from bin Laden's phone, Slahi became a target for U.S. law enforcement.

After the 9/11 attacks, he was arrested in Mauritania. The CIA then took him to Jordan before eventually sending him to Guantanamo, where an "enhanced interrogation" program was approved for use on him by then-Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld. Techniques used on Slahi have since been made illegal.

He said the torture broke him. To stop the pain, he confessed to crimes he didn't commit and to criminal plots that didn't exist.

"I falsely confessed to crime," Slahi admits in the broadcast piece. "It was bad business. Bad business."

In 2004, the military officer chosen to prosecute him resigned from the case, saying later that he was "convinced that Slahi had … been the victim of torture."

In 2010, a federal judge ordered Slahi's release and wrote that there is ample evidence "Slahi was subjected to extensive and severe mistreatment at Guantanamo."

In the years Slahi spent in prison, he soaked up American language and culture. He watched "The Sopranos" and "The Big Lebowski" and he read books like "The Catcher in the Rye" and "Divine Secrets of the Ya-Ya Sisterhood."

He also maintained a keen sense of humor. When Hollander asked him how many times he had been interrogated, he responded, "That's like asking Charlie Sheen how many girlfriends he has."

But on the subject of torture, Slahi doesn't joke.

"He's obviously very scarred by what he went through," Williams says "And yet, he managed to get out. He managed to come home, and he came home with his dignity and also with this idea that he doesn't hold a grudge."

"He's not angry, and he forgives. I think that's very powerful."

This video was originally published on March 12, 2017.