The United States of Insecurity

The American dream has inspired generations to work hard with an eye toward climbing the socioeconomic ladder. But when the Pew Research Center asked Americans whether they would rather have more money or economic stability, 9 out of 10 choose stability.

What happened to turn Americans away from the country’s long-held belief in personal economic growth? Shifting dynamics in the labor force as corporations and the government increasingly push costs and risks onto workers are among the causes, according to a new groundbreaking financial study that tracked the daily financial lives of 235 U.S. households for a full year.

The U.S. Financial Diaries (USFD) followed low- and moderate-income households in four communities who agreed to share their intimate daily financial details. While other studies of household finances have examined annual data, the USFD project is unusual in its level of detail about how Americans are making a living, spending their money and dealing with financial stress.

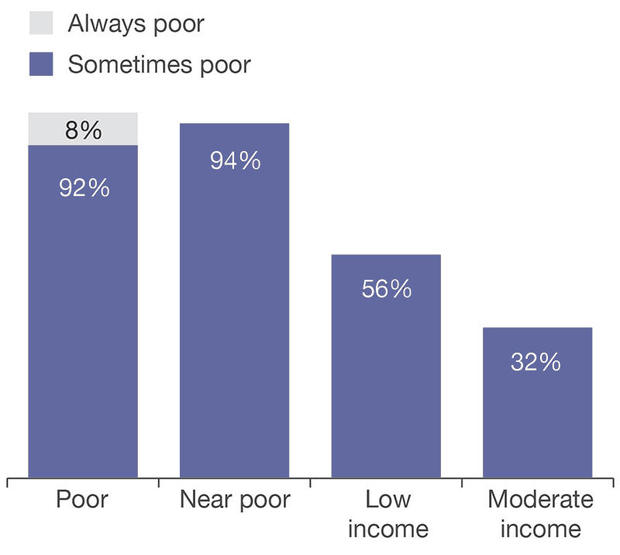

The findings are startling. For instance, the researchers discovered that even middle-income families are spending part of each year in poverty.

“Many people who are middle class nevertheless have the experience of being poor over the course of the year,” said Rachel Schneider, a co-author of “The Financial Diaries,” a book published this month by Princeton University Press about the research, which was funded partly by the Ford Foundation, the Citi Foundation and the Omidyar Network.

“It’s not being able to pay all their bills,” Schneider added, “not being able to afford their groceries, having to think about putting gas in the car, having to think about whether to cancel their cable. When you work full time and still have that experience, it feels unfair.”

That sense of injustice was expressed at the polls in November, when millions of white, working-class voters placed their hopes in Donald Trump’s plan to revitalize manufacturing and “make America great again.”

Yet those hopes aren’t likely to materialize, Schneider said, because President Trump’s plans aren’t addressing the underlying labor market problems that have caused middle-class families to feel their houses have been built on sand. (Schneider noted that the researchers didn’t ask families that participated in the study about their political leanings or who they voted for in November.)

“There’s so much focus on the loss of manufacturing jobs, but they aren’t intrinsically good jobs,” she said. “In the industrial revolution, manufacturing jobs were 100-hour-per week jobs, with incredibly high risks and bad health outcomes, but policies enabled those jobs to become good jobs.”

That is, the industry isn’t as important as the quality of the job. And in the recent economic era, job quality has declined as corporations shift costs and risks onto their employees. Among those shifts are higher-deductible health insurance plans and the abandonment of traditional pensions in favor of 401(k) retirement plans. Such moves add both expenses and liabilities to workers’ daily lives while raising corporate profits.

“It might be [Trump] can keep a manufacturing plant from offshoring, but what’s he doing to make sure those jobs are high-quality jobs?” Schneider asked.

Since the 1970s, steady jobs that pay predictable wages with strong benefits have become scarcer. Professional and technical jobs boomed between 1940 to 1980, but growth has slacked since then. At the same time, service jobs have taken a larger piece of the economic pie, leading to what Schneider and her co-researcher, New York University professor Jonathan Morduch, call the Great Job Shift.

That’s leading to greater income volatility, since many of those jobs are based on hourly wages. Corporations rely on job-scheduling software that can cut back a worker’s hours based on demand. While the corporation profits, the worker is left with unpredictable wages and a headache trying to manage her budget.

An analysis of the income instability that the USFD families experienced found that almost half of overall volatility was due to changes in income from the same job, making it the largest source of income swings. Americans may be employed, but they can’t count on their employers to provide steady wages.

“The unemployment rate is low, our economy is doing fine, but that doesn’t change that people’s day-to-day lives feel quite insecure,” Schneider said. “They don’t feel hope that they can have lives they had expected to have.”

The case of the Moore family of Ohio, one of the households in their study, illustrates that experience. Jeremy Moore had a full-time job as a mechanic, but his hours fluctuated depending on local demand, which spiked in the summer and winter months. At other times of the year, his employer had less work for him, so he earned lower wages. In some months, the family ran low on money and borrowed from relatives to pay bills.

In the end, Moore decided to take a lower-paying job with a longer commute because it had greater wage stability, guaranteeing him 40 hours of paid work each week.

Said Schneider: “He’s working full-time, so shouldn’t you be able to pay your mortgage? But Becky [Moore] felt they were on the edge, and she had to apply for food stamps. She felt bad about it. I think her words were, “There are people who are worse off than us.’”

The USFD research is part of a recent surge in interest in household income volatility, especially given the financial stresses of the Great Recession and anemic wage growth in the economic recovery. Large ebbs and flows in household incomes can hurt families both materially and psychologically, according to research published earlier this year from The Pew Charitable Trusts, which found that income spikes and dips are common across all demographic groups.

One-third of moderate-income USFD families experienced at least one month below the poverty line, which surprised Schneider. By comparison, 56 percent of low-income families slipped below the poverty line at some point during the year.

“I do think the day-to-day insecurity is why people are mad,” she added. “Most workers feel their jobs aren’t secure. Having put in 10 years at the company does’t mean you’ll get another 10.”