The evolution of the psychoanalyst's office

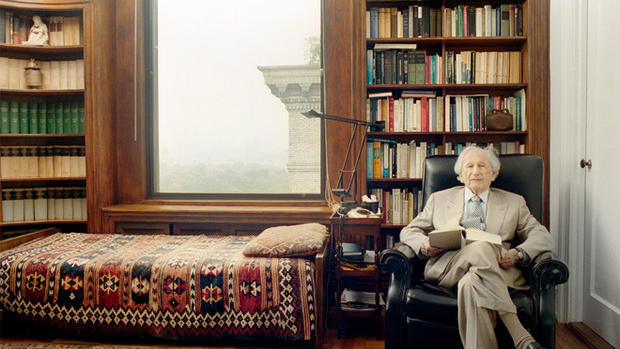

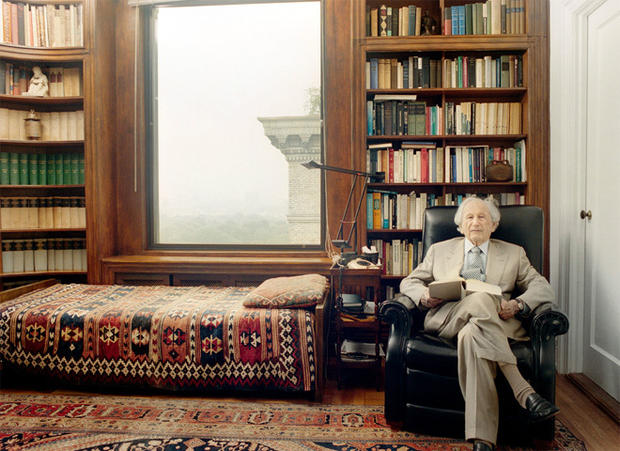

(CBS News) New York psychoanalyst Mark Gerald is also a photographer, and for more than ten years he has photographed other psychoanalysts' offices, as part of a project called "In the Shadow of Freud's Couch." The images have been exhibited in New York and Athens, Greece, and can be found on the web at markgeraldphoto.com.

In this web-exclusive interview, he talked to Susan Spencer about the evolution of analyst's office space since the time of Sigmund Freud; the importance of objects and artwork for both analyst and analysand; and the ubiquitous couch.

Mark Gerald: "When you train as a psychoanalyst, you sit in psychoanalysts' offices. You go to classes, you study with psychoanalysts. So I had plenty of time to look around many different offices. And I do remember one particular moment in which I was sitting in a psychoanalyst's office with a seminar of other trainee analysts. And the instructor was saying there's no such thing as a basic aggressive drive. And I was looking over his head, and there were these primitive masks that were there, all quite frightening."

Susan Spencer: "Very aggressive!"

Gerald: "And I thought, I wish I could get a picture of this! I had studied to be a photographer, and I thought this would be a great picture, and I'd call it, 'There's no such thing as an aggressive drive.' (laughs) So that was a moment that sort of coalesced what had been brewing for me for a long time."

Spencer: "What was your your goal, really, in doing this?"

Gerald: "Well, that's a very important question. I was aware that psychoanalysis is changing a great deal. But the public really hasn't understood that it has changed. Most people's conception of psychoanalysis comes from New Yorker cartoons, Woody Allen movies -- you know, the analyst is always an old white man with a little beard, sitting with his pad behind the couch.

"And I knew that the psychoanalytic institutes that I was involved in [and] beginning to teach in were getting a much more diverse group of people, candidates, coming in to be psychoanalysts. Many more women -- in fact nowadays, most psychoanalysts who are in training are women. Many more people of color, people diverse, from different cultures and backgrounds.

"Psychoanalysis in many parts of the world is actually becoming of great interest, and I wanted to show that. I wanted people to see that this is a very diverse group of practitioners. And I also thought that seeing people in their work space would really give a feel for what was going on. Now, psychoanalysis is not something that has really been open to access. Some of the principal things in psychoanalysis [are] privacy, confidentiality, and this is not only true for patients, but for analysts as well."

Spencer: "I'm surprised they let you in."

Gerald: "Had I not been an insider, I would not have been able to come in. I have some colleagues who are photographers who have tried to do a similar kind of endeavor. One I know, for example, did psychoanalytic chairs. He was able to get in there and do the chair. Just the chair, but not with the analyst present.

"This goes to a very central thing, I think, in my project and in the interest of psychoanalytic offices, in that all of the objects in the analyst's office, whether they're intentionally designed or brought in, or created, have meaning. 'Cause psychoanalysis is a practice of looking at and trying to understand the meaning of experience, and not only the surface meaning, but the more underlying meaning."

Spencer: "Is this something that the patient is aware of?"

Gerald: "Well, patients -- when they begin the process of a psychoanalytic treatment -- begin to become more and more interested in different layers of their own experience."

Spencer: "So what they're experiencing in that office, to the point of just what's around them, becomes very important."

Gerald: "It can be. It's not uncommon, for example, that a patient, sitting in a psychoanalyst's office for three or four years, might one day say, 'Oh, when did you get that new picture on the wall?' And it turns out the picture has been there all along. So why did they know in that moment, how did they come to discover that picture, to find it? That's part of the psychoanalytic process, that you are finding things that have been there all along, but were not available to awareness."

Spencer: "So if a patient becomes that sensitive to the surroundings, then what's in that office is really important."

Gerald: "I think so, yes.

"The first office that I photographed was my own, and it was a self-portrait. And part of the motivation for that was I wanted to see myself in my work. One of the things that we're very interested in is increasing and expanding consciousness and awareness about experience. And I realize that I couldn't see myself. No one can see themselves, after all. So I wanted to see what I saw, by looking at myself."

Spencer: "So what did you learn about yourself?"

Gerald: "Well, I learned that it took a while to become a good subject for the camera! That is, to relax into the experience. And I think this is true for analysts, especially young analysts, that it takes a while to become comfortable within yourself in doing the work that you do.

"You know, we study a lot, we learn a lot, we have a lot of forebears that we try to model ourselves after. And it takes a long time to differentiate and finally separate ourselves into having a personal psychoanalytic voice, and a personal psychoanalytic self. And this brings us to Freud's office, because this is the iconic psychoanalytic office: 19 Bergasse in Vienna.

"It's been refurbished, so it's a museum and you can go there. And it's a fascinating place. And the couch -- of course, you say psychoanalysis, you think couch. The couch is very small, and rather than being a couch that you lay down sort of horizontal, it's loaded with pillows so that the patient was really sitting up, essentially. But the designs and the creation of that first office became sort of internalized, without a lot of awareness, into all future psychoanalysts' office."

Spencer: "So you think psychoanalysts today are still modeling their offices after Freud's office?"

Gerald: "There are elements of it that are undeniable. There's not a psychoanalyst who've I've photographed -- and I've photographed analysts in South America, in Mexico, in Europe, in the United States -- who does not have a couch in their office. One of the senior New York analysts who actually works in a psychoanalytic approach called interpersonal psychoanalysis, which does not use the couch, he said, 'I never use the couch with my patients, they always sit up. But if I didn't have a couch, I wouldn't feel like a psychoanalyst.'"

Spencer: "This legitimizes you."

Gerald: "Right. It's your uniform. I mean, after all, we don't have stethoscopes, we don't have X-ray machines, we don't have uniforms of one kind or another. But you're gonna have that couch, yeah!"

Spencer: "What would a patient think if they walked in and didn't see it?"

Gerald: "I think they'd think they're going to see a cognitive behavioral therapist!" (laughs)

Spencer: "So what common motifs and themes have you picked up on over your years of photographing these offices?"

Photos: Inside the analyst's office

Gerald: "I'm very interested in showing diversity in the offices, and there are very interesting distinctions. But most offices carry with them a few basic ideas. And these are connected to the notion that a psychoanalytic office is an enclosure. It's a place for privacy, a place to get at and reach areas that are not easy to reach in the social world."

Spencer: "So you should first of all feel safe in the office."

Gerald: "Very, very much. I mean, all offices are in closed rooms. No picture windows, unless you're looking out over the Rockies, or someplace where no one else is going to be looking back. They have doors, and the very notion that when you go into an office, the door is closed behind you. You're in this place that is private, and it's an opportunity to open up areas that have been private in parts of yourself -- secrets, shameful areas, trauma. You know, areas that are just difficult to get to.

"Now, along with that, then there's the question of what is most conducive to that type of revealing or opening up, to be doing so safely? And one of the things that is often found in most psychoanalysts' offices -- and again, this trends back to Freud's office -- are pieces of art, either paintings or objects, and books. These are very common. I've come across some exceptions, but for the most part offices have these. And these are important because these are evocative objects. Most art in analysts' offices often have an abstract quality to it.

"Now, one of the analysts that I photographed, he's an Israeli analyst, he has in his office a sequence of images of the blasting of the atomic bomb -- a very unusual image to have in the office."

Spencer: "That would scare me to death!" (laughs)

Gerald: "It might scare one person to death, and another person might welcome something very eruptive in themselves that they could see in this space, the opportunity and the possibility of being able to bring up some of the things that feel uncontainable in themselves. . . . He practices in the United States, and many of his patients were ex-pat Israelis. So I think there was something that would resonate with them having lived in a culture and in an environment where violence and war was not uncommon."

Spencer: "So the office can tell us as much about the psychoanalyst as it can be affecting the patient?"

Gerald: "Yes, yes.

"I think that the books and the paintings are, for the most part, selected -- books are often selected because they're read by the analysts or they're part of the analytic training. A lot of analysts consider themselves being held by their own office. And I was thinking about this recently, the objects that analysts choose for their office are in part for their patients to use and react to.

"But they're also important for the analysts to create a space for the analyst to be comfortable in. The reason for that is that analytic work involves the analyst having a free mind to work with their patient, to be able to resonate with different elements of their own mind and their own being. And in their own environment, with their own objects, they often can do that more freely."

Spencer: "Common themes, apart from the objects that you're talking about?"

Gerald: "Themes are often themes that are designed to get at deeper areas of experience, things that are maybe not so obviously depicted. Things that may have a dream-like quality. I mean, in addition to the couch, you think of psychoanalysis, you think of dreams and of analyzing dreams.

"And dream space can be important in terms of creating space that's conducive to dreams. Freud called dreams the royal road to the unconscious. What he meant by that was that it was a use of a language to get at experience that was not easily accessible otherwise, through prose or through more objective language."

Spencer: "What about lighting? You mention dreams and relaxation and so forth. How critical is lighting?"

Gerald: "I think it's very important. I think that many analysts have offices where the lighting is more subdued, it's darker. It's closer to the kind of atmosphere that would sort of precede going to sleep. Now, you don't want your patient to fall asleep on you, and you certainly don't want to fall asleep yourself!"

Spencer: "It's just a soothing level."

Gerald: "It's the kind of thing that, you know, people get massages, and at certain point they begin to drift. You're conscious, but you're available to information from yourself that may not be available otherwise."

Photos: Inside the analyst's office

Spencer: "Does color matter?"

Gerald: "I think it does, and I can tell you from my own experience that I've had three different psychoanalytic offices, and in each of these offices that I've had, I've painted the walls the same color. They've always been painted with Benjamin Moore number 5202. It's sort of blue-gray, somewhere between a sky and the sea, and a color that I find very conducive to my own analytic state of being, of being able to listen. I always used it, and it accompanied me from office to office. And by the way many of my patients also accompanied me from one office to another."

Spencer: "So they felt at home. You still like it?"

Gerald: "I do, I do. I'm very comfortable with it."

Spencer: "You've listed a number of things that seem fairly important. Do you think that psychoanalysts for the most part -- or any of us really in the offices that we have -- pay enough attention to this stuff?"

Gerald: "No, I don't think we do. I think that we create worlds around us that are extensions of our inner life. We're not always aware in doing so, whether we're decorating our house or we're going to a hotel and finding the one that we're picking on the Internet 'cause we like the way it looks. I think that these often revert back to very early patterns that people learn in their earliest homes, that we become familiar with the way space is affecting us, and is impinging or becoming holding for us. And that these are places we then gravitate towards in life."

Spencer: "Things that make us feel, what, secure?"

Gerald: "I think familiar would be a better way to put it, because there are situations -- I think of a patient who had been abused as a child quite profoundly, and he told me about his childhood home, that it was always cold, that the paint was always peeling off the ceiling, and that nothing that broke in this home was ever fixed. Now, this really captures the state of a child who was traumatized, abused, not protected. And this is the orientation that this person moved towards.

"And coming into a psychoanalytic office, for someone who has had such damage, is an experience of also having a new possibility, of creating a new home -- not only [a] new home that is the space that's outside, but because that's associated with someone who's listening, who is interested in what happened, who the unspeakable can be spoken to, it becomes a new home inside one's self. It's now a safer place. And this is part of what the space of the office can do for the psychoanalytic treatment."

Spencer: "So if you were called upon to advise a psychoanalyst, new person setting up an office, what have you learned? What tips would you give them as to how to best use the office as a tool in the practice?"

Gerald: "It sounds as though this could be another career for me -- the psychoanalytic interior decorator. (Laughs) But I don't quite see myself that way. But I think it's a very important question, because the first thing that I would bring up with an analyst setting up the office is to suggest to them that they bring into the space objects that are important to them, that there be some things in their office that have personal meaning and that are grounding elements for them."

Spencer: "Do you feel like you have to be careful with what you put in the office in the sense of a patient becoming upset, or attaching too much meaning, or reading something into it?"

Gerald: "I think there are things that might disturb people, that I always am thoughtful about the things that I bring it. I think the first layer of consideration is, am I comfortable with it? . . .

"After Freud's office, which was very personal and filled with his collections and his hobbies, there was a trend that became, I think, a mistaken trend, to set up psychoanalytic offices very impersonal, to have these offices be almost like operating rooms, surgical rooms, so that there would be nothing there that would be distinctive. The thinking was this would be an opportunity to get to deeper things in a patient if [nothing would interfere]. But I think actually those were more depriving environments -- not only depriving for the patient, but depriving for the analyst, to sit all day in such a dry and antiseptic space. So I would suggest that you start with bringing yourself into the space.

"And that is an organic process, it doesn't happen at once. Although the color of my walls and many things in my office have been here from the beginning, I add and changed things periodically. Some things come by way of travels that I've done, and see something that just speaks to me and want to bring it back because I feel as though it's going to bring something into the work that will be evocative for patients. Here and there, a patient will sometimes -- and this is true for many analysts, not all -- give them a gift, sometimes at the end of their treatment. And that's a complicated area, because that's a whole 'nother interview!"

Spencer: "I didn't know there was an end!" (laughs)

Gerald: "Well, that's another point, very good point, yes." (laughs)

For more info:

- "In the Shadow of Freud's Couch" by Mark Gerald (markgeraldphoto.com)

- Freud Museum, Vienna