SpaceX launches cargo to ISS, fails landing attempt

A SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket boosted a Dragon cargo ship into orbit Tuesday on a three-day flight to deliver nearly 4,400 pounds of equipment and supplies -- including an espresso machine -- to the International Space Station.

The climb to space was picture perfect, but an attempt to land the rocket's first stage on a barge stationed some 200 miles east of Jacksonville -- a key step in SpaceX founder Elon Musk's drive to lower launch costs -- was not successful. The rocket made it down to the barge, but it tipped over after touchdown.

"Ascent successful. Dragon (cargo ship) enroute to space station," Musk tweeted about 25 minutes after launch. "Rocket landed on droneship, but too hard for survival."

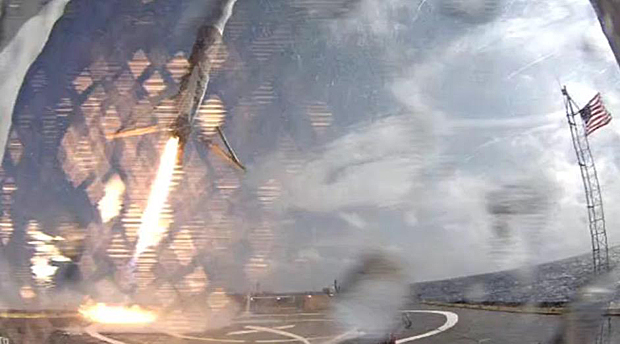

SpaceX tweeted photos showing the booster descending under rocket power just above the deck of the barge with its four landing legs extended. A second photo showed black smoke swirling around the base of the rocket, apparently just before or after touchdown. Musk tweeted: "Looks like Falcon landed fine, but excess lateral velocity caused it to tip over post landing."

A video posted Tuesday night by SpaceX showed the rocket descending toward touchdown, tilting from side to side as it closed in on the landing platform. The video ends before the rocket tipped over.

Earlier attempts to land on the barge, named "Just Read The Instructions," were not successful due to to stormy weather and problems with stabilizing fins needed to help control the descent. SpaceX fixed the technical issues, but pulling off a successful landing remains an elusive goal.

For his part, Musk has never promised better than 50-50 odds for the initial landing attempts. But in a tweet earlier this week, he said he hopes the company can achieve an 80 percent success rate by the end of the year, after gaining experience through multiple flights.

And in any case, Tuesday's landing try was a strictly secondary objective. The primary goal of the flight was to get the Dragon cargo ship into orbit and safely on its way to the International Space Station. And that part of the mission went off without a hitch.

Running a day late because of approaching bad weather, the Falcon 9 roared to life on time at 4:10 p.m. EDT (GMT-4). With its nine first-stage engines generating some 1.1 million pounds of thrust, the slender rocket majestically lifted off from launch complex 40 at the Cape Canaveral Air Force Station and streaked away to the northeast.

The kerosene-fueled Merlin 1D engines fired for a little under three minutes to boost the rocket out of the dense lower atmosphere. At that point, the Falcon's single-engine second stage took over, propelling the Dragon capsule to orbit. A few minutes later, the spacecraft was released, its two solar wings unfolded and the capsule set off after the space station.

If all goes well, the Dragon will reach the lab complex early Friday, pulling up to within about 30 feet and then standing by while Italian astronaut Samantha Cristoforetti, representing the European Space Agency, locks on with the station's robot arm. Ground controllers then will remotely operate the arm to pull the capsule in for berthing at the Earth-facing port of the forward Harmony module.

For SpaceX's sixth operational resupply flight, the Dragon was loaded with 1,142 pounds of station hardware, 1,860 pounds of science gear, 1,102 pounds of crew supplies -- including a month's supply of food -- and another 86 pounds of computer gear and spacewalk equipment. Also on board: 20 mice serving as test subjects in research to learn more about the effects of weightlessness.

The Dragon will remain attached to the station for 35 days, a record duration for SpaceX that is required in part by the rodent experiment to learn more about the effects of microgravity on bone and muscle loss. By the time it departs in late May, the station crew will have repacked the capsule with more than 3,000 pounds of research samples, no-longer-needed equipment and trash. The Dragon is the only cargo ship currently flying to the station that is capable of bringing material back to Earth.

SpaceX holds a $1.6 billion contract with NASA for 12 resupply missions to deliver some 44,000 pounds of cargo to the station. NASA recently ordered three additional flights to help offset a resupply shortfall triggered by the failure of an Orbital Sciences Antares rocket last October. Contract details have not been announced.

Recovering the first stage of the Falcon 9 rocket is not part of the NASA contract, but it is a key element in the company's ongoing push to lower costs by recovering, refurbishing and relaunching booster stages.

The latest flyback attempt started just after stage separation less than three minutes into flight. Three rocket firings were planned to slow the booster and set up a descent to the landing barge.

First, the booster presumably flipped 180 degrees to an engine-forward orientation for a so-called "boost-back" firing, a three-engine burn lasting about 30 seconds to keep the stage from flying too far down range and to set up a trajectory toward the landing barge. After the engine firing, four "grid fins" near the top of the stage were expected to deploy to help control the booster's orientation.

"After that, we will coast, we will reach about 125 kilometers (77 miles) and then come back into the atmosphere," Hans Koenigsmann, a SpaceX vice president, told reporters Sunday. "That's the time we do an entry burn. The entry burn is literally tapping the brake a little bit so it doesn't get too hot during the entry. That entry burn is fairly short, it's about 10, 15 seconds, and it happens about seven minutes into the flight."

Finally, a single engine was expected to reignite to slow the booster even more and lower it to a gentle touchdown on the deck of the "Just Read the Instructions." But at some point during the descent, something apparently didn't go according to plan, resulting in a hard landing on the deck of the drone ship.

As it turns out, SpaceX is not the only major rocket builder looking into recovering, refurbishing and reusing booster components. On Monday, SpaceX rival United Launch Alliance, builder of workhorse Atlas 5 and Delta 4 rockets, unveiled plans for a new next-generation rocket featuring recoverable first-stage engines.

Unlike SpaceX, ULA does not plan on recovering entire booster stages, arguing too many flights are needed to recover costs. Instead, the new rocket's methane-powered engines, built by Blue Origin, a company owned by Amazon-founder Jeff Bezos, will separate from the spent first stage of the new "Vulcan" rocket and fly under a parasail into the lower atmosphere where a helicopter will pluck it out of mid air.

The new Vulcan rockets eventually will replace ULA's Delta and Atlas families, dramatically lowering costs, the company says, and ending reliance on Russian engines that currently power the Atlas 5.

The new rockets also will heat up the already intense competition between ULA and SpaceX, which has been waging an aggressive campaign to win military launch contracts, arguing against the higher cost of the Delta family of boosters as well as the Atlas 5 and its Russian-built RD-180 engines.