Road to Redemption

Produced by Chris O'Connell, Doug Longhini and Lauren Clark

(CBS) CHICAGO -- "The journey of the last 25 years has really ... tested my faith," said Jeanne Bishop.

"Palm Sunday 1990. I'm in my choir robe at the back of my church -- where I still sing in the choir today. ...This glorious music is playing. The church is full. Everyone is singing. It's this joyful procession ... And the last thing I expected was to have the church secretary come to me and put her hand on my arm and say, 'You have a phone call.'

"And that's when my heart started to pound. Because I thought, 'Something's wrong, really wrong,'" she continued. "And it was my father on the phone. ...And the first thing he said to me is that, 'Nancy and Richard have been killed.' ...And he said, 'Someone killed them.'

"This happy young couple with everything to live for, with no enemies, you know, with no reason that anyone in the world should want to take their lives.

"It took 23 years to get the answer of why ... where you can't see too far in front of you. Where it really is kind of taking one step and then another step and another step."

More than 25 years after the brutal murder of her sister, Nancy, and brother-in-law Richard Langert, Jeanne Bishop still lives in the wealthy Illinois suburb of Winnetka, where they grew up.

"It was such a happy childhood," Jeanne said. "I was the middle of three girls, my younger sister, Nancy, and my older sister, Jennifer."

It's a community where many Chicagoans move to raise their families and used by filmmaker John Hughes for movies like "Home Alone" to convey picture-perfect Middle America.

"It looks pretty idyllic when you're walking down the street," "48 Hours" correspondent Maureen Maher observed.

"It's a real quiet, safe community," said Jeanne.

That's what made the sound of sirens so shocking that Sunday in April 1990. Nancy's father, Lee, went to check on his pregnant daughter and her husband.

"He had gone to the townhouse and rung the doorbell. And there was no answer. ...so, he let himself in," Jeanne said. "And then, noticing the light on in the basement ... he went to the top of the basement stairs, he looked down. And there were Nancy and Richard."

"And he could see them?" Maher asked.

"Frozen in death ... his youngest daughter and his son-in-law," she replied.

But who would commit such a gruesome and deliberate crime? It would take a long time to answer that question, and even longer for Nancy's family to find a path to forgiveness. Two-and-a-half decades later, it is still a work in progress.

"How would you describe this 25-year-long journey that you've been taking since your sister's murder?" Maher asked Jeanne.

"Oh, I think it's been this incredible - adventure. ...At the heart of it was Nancy," she replied. "Every time I get to say her name, every time I get to tell her story, it's a way of making sure that the world does not forget her."

"Oh, she was the comedian," Jeanne continued. "And -- when she got older, she was kinda the one who could get away with anything."

"She was fun. Fantastic sense of humor," oldest sister Jennifer Bishop-Jenkins said with a laugh. "My mother is very, very classy, well-mannered, elegant lady. And Nancy would be the one that could just make her laugh to the point where she would say, 'Oh, that's awful [laughs]. Oh, that's awful.'"

Joyce Bishop says her daughter, Nancy, was also a gifted performer, excelling at Winnetka's competitive New Trier High School, but Nancy's aspirations stayed rooted in family.

"She wanted to be a wife and a mother. And have a home," Joyce said. "That was all she wanted. And she was on her way."

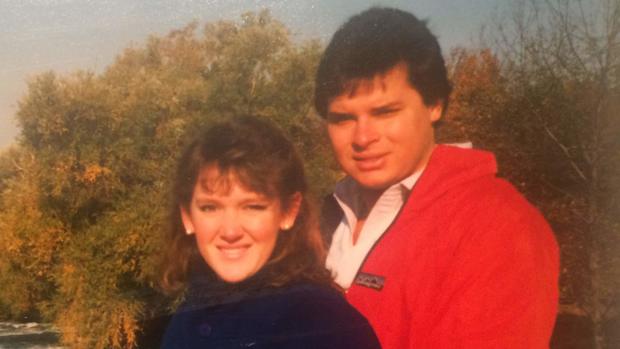

In her early 20s, Nancy Bishop met Richard Langert.

"Oh, I thought he was just this perfect match for Nancy. Because he was this tall, handsome jock," Jeanne said. "And he would just be kinda basking in this glow that she cast. ...He would kind of look at her like, 'Isn't she the most wonderful thing?'"

"I would look outside. And he would be out mowing our lawn without having been asked. Now, is that a good guy?" Joyce said with a laugh.

"That is a good guy. That is a smart guy," Maher remarked.

They married in 1987, and were soon working together for a growing coffee company.

"Every month, she was hoping and praying and wishing that she would get pregnant," said Jeanne.

Within a few years, Nancy found out she was pregnant.

"She actually said, '1990, this is gonna be our year.' Because they had been married three years. They were expecting their first child. They were moving into their first house. She was so happy," said Jennifer.

But until their dream house was ready, Nancy and Richard were temporarily living in a townhouse owned by her parents.

"They really were just living out of a suitcase more or less," said Joyce.

On Saturday, April 7, the family got together at a restaurant in Chicago to celebrate Lee's birthday and Nancy's big news.

"Nancy and Richard were just, you know, in their heyday. They loved it," said Joyce.

"I had a baby gift all ready for Nancy. And, oh, we were just the happiest family you could imagine," said Jeanne.

"What do you remember being the last words that you said to her that night?" Maher asked.

"Oh, I remember exactly. Because I never say them now. I hugged her goodbye. And I said, 'I'll see you tomorrow.' And I never say that to anyone anymore. Because ... you don't know that the will be true," Jeanne replied.

When Nancy and Richard returned to the townhouse that night, their killer was already inside waiting.

WBBM News report: "The husband was executed, shot once in the head with his hands handcuffed behind his back. The wife was shot three times in the upper body."

"Everything in me stopped. I-- if you had sliced my wrist, I would not have bled," Joyce said. "I was frozen. ...I didn't cry. I didn't feel a thing."

"Surreal?" Maher asked.

"Surreal. I didn't cry until the next day," she said.

The news of a double murder hit at the heart of this quiet community. As neighbors waited for answers, investigators at the crime scene had many questions about the killer.

"There was nothing taken, nothing -- no jewelry, no electronics, $500 of cash ... strewn on the ground, almost as if it had been handed to him, like, 'Here. Take this,' and he had tossed it aside like, 'That's not why I'm here,'" said Jeanne.

"What did that say to you?" Maher asked.

"That said to me this is a crime that is meant to be seen as an assassination -- an execution," she said.

"That it was planned, methodically planned?" Maher asked.

"Right. Yes. Yes," Jeanne replied.

A multi-town police task force was assembled, and Sergeant Gene Kalvaitis was put in charge of solving the murders.

"It was hard to understand," he said. "As much as some things -- look professional, other things just look so amateur."

One thing they did quickly determine was how the killer came and went undetected.

"In the backyard right near the point of entry, through the patio door, there's a fence there," Kalvaitis explained. "Once you're over the fence ... there's a bike trail down there and you can go all the way to basically Chicago on it."

Rumors spread about an outsider bringing big city violence to Winnetka, but the question of 'why them?' remained.

"You do a check on everybody, I mean, when you have no suspect, everybody is suspect," said Kalvaitis.

"Everyone and everything is fair game. ...I understood that, and so did my family," Jeanne said. "What troubled me was the notion that my sister's investigation was hijacked for some other purpose."

WHO KILLED NANCY & RICHARD?

"I knew that if someone killed them, that evil had intruded into our lives like nothing that we had ever known before," said Jeanne Bishop.

In the days after the murders, the Bishop family learned from investigators chilling details of what happened in the last moments of the couple's life.

"Richard died first. The gun was put to the back of his head. He was shot once, execution style," Jeanne explained. "Nancy ... was shot twice in her side and abdomen. And then, I think at some point, she must have realized she was dying. And, so ... she dragged herself by her elbows over to Richard's body where he lay."

"And the last thing that she did before she died was to leave us a message in her own blood. She took her own blood and she drew a heart and a U. 'Love you,'" said Jennifer.

"Oh, it's probably the most heartbreaking thing that you could ever imagine. When I saw that heart there, mine broke," said Joyce.

When Det. Gene Kalvaitis walked into that basement, he saw the brutality of the slayings firsthand along with some odd clues.

"There was blood everywhere, you could smell it," he said. "And there was a set of handcuffs laying there."

Near the back fence, a single glove.

"From the onset of that case we had very, very, very little evidence to go on," said Kalvaitis.

Investigators looked into the Nancy and Richard's lives. Rumors of a drug connection to the coffee business they worked for were quickly dismissed. Meanwhile, family members wracked their brains for any clue they could come up with.

"Could you think of anyone who would've wanted to hurt them or anyone who had something -- any sort of revenge or anything out for Nancy and Richard?" Maher asked.

"Absolutely not," Jennifer said, her mother shaking her head in agreement."Completely mystified. Not a single thing."

But other tips came in, including one that involved a possible link to the IRA -- - the Irish Republican Army - and to Jeanne. Jeanne, who along with being a corporate lawyer, was involved with human rights work.

"The FBI had a theory," Jeanne explained," that because I had been doing human rights work in Northern Ireland ... the IRA had thought that my human rights work was actually a cover for being in the CIA, and they had come to Winnetka to kill me, and had mistaken Nancy for me, and that they killed the wrong person, and that now I should tell them everyone I knew in Northern Ireland and all about them so they could solve the murder."

The FBI also claimed that there had been a death threat made against Jeanne by the IRA several months earlier. And given the fact she had just returned from a trip to Northern Ireland three days before the murders, and investigators had some questions for her.

"And I confronted her with -- with that threat and she simply ... didn't believe it," said Kalvaitis.

"I was so shocked at this theory. I said, 'The IRA doesn't target Americans," said Jeanne.

"And I kept expressing that to Jeanne," Kalvaitis explained. "'You have to understand where I'm coming from. You have your sister who was pregnant was killed. Her husband was killed -- brutally.' ..."I need to find out who did that.' And I go, 'I'm kinda surprised that you don't wanna help.' She wouldn't budge."

"Did you feel like suddenly there had been a line in the sand drawn between your family and investigators?" Maher asked Jeanne.

"I felt at the time that they were considering me uncooperative. And that's a thing that you never want to be," she replied.

But that's how the media in Chicago was playing it.

News report: Winnetka Police have indicated that Jeanne Bishop, shown here with other family members, has not cooperated with authorities in the investigation of the double slaying.

"And, so, on the news, they actually did this kinda little spotlight around me, you know, as if, like, 'there she is.' And I thought, 'Really, if-- you believe that my life is being threatened and I am still a target for whoever didn't succeed in killing me, and now you're highlighting my picture on the news?'"

But the IRA story and a connection to Jeanne never checked out. As the weeks dragged on, it really did look like the killer might get away with it.

"Did you get to that point that you thought, 'We may never know who did this?" Maher asked.

"Yes. Although my heart didn't wanna accept it. I mean, I just felt so strongly that, you know, it would be this terrible, you know, shadow over my mother and my father and my sister and myself," said Jeanne.

Meanwhile, Gene Kalvaitis was still holding out for that one perfect tip to come in.

"I was just hoping that somewhere along the line -- that we'd get the break that we needed," he said.

After following a series of false leads, dead ends, and spending about a million dollars, the task force shut down. But then, nearly six months after the murders, two teenagers walked into the Winnetka Police Department with an incredible story and blew the case wide open.

A SURPRISING SUSPECT

Six months after the murders of Nancy and Richard Langert, Winnetka Police Sgt. Patty McConnell was on duty when two teenagers walked into the station, asking about the witness protection program.

"Do you think they're playing a joke or did they look afraid?" Maher asked.

"No, they definitely were not playing a joke," Sgt. McConnell replied. "He was clearly very nervous."

He was Phu Hoang, a senior at New Trier High School, who walked in with his girlfriend.

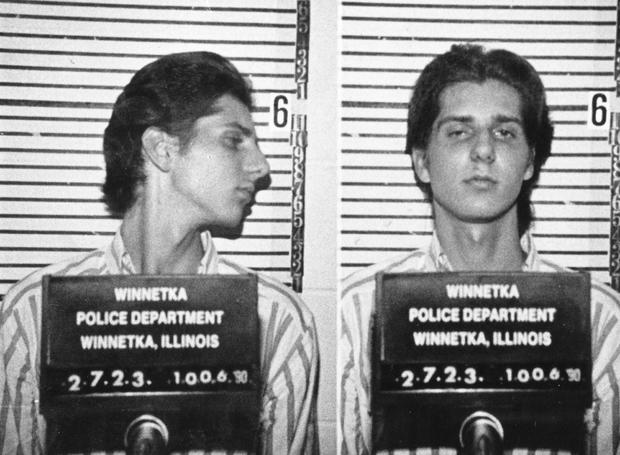

"He said, 'You know, I know who did the Winnetka murders,'" McConnell said. "'My friend, David Biro ... he told me that he did it.'"

David Biro had bragged to his good friend about the killings, but said nothing about his motive.

"And then he said, 'You know, he's got a gun -- in his room. He showed me the gun,'" McConnell continued. "He said he got afraid that he thought he was gonna kill again."

Biro was no stranger to the Winnetka Police.

"A small-time punk to me is how I would characterize him," McConnell said. "I was very skeptical. ...I believed that David had told him that he killed them, but I didn't believe David did it."

That is, until Hoang described something Biro had said about what happened at the crime scene.

"He said, ' You know, he got nervous after he was talking to them ... and he popped off a round.' And when this kid said that to me all the hairs on my arm and my neck stood on end. Because I knew that they had discovered a round in the wall on the first floor just above the baseboard. And I knew that that detail had not been in the newspapers," said McConnell.

"So only the killer could have known," Maher remarked.

"Yes. And ... I was, like, chilled that, 'Oh my God, he did do it," said McConnell.

Biro was arrested the next day without incident outside his family's house. And a search warrant was issued for his padlocked bedroom.

"And the first place we went, is we looked under the bed to see ... if a gun was laying there, in fact there was," said Gene Kalvaitis.

It was a stolen .357 Magnum, which tests concluded was the murder weapon. That's not all they found. Biro had handcuffs similar to those found on Richard Langert and a scrapbook of articles on the killings. But Biro told police he was only holding the gun for a friend.

"Did you question Biro?" Maher asked.

"I did. ...I would say he was very arrogant. Smug," McConnell replied. "Partly, I think, because ... there was all kinds of speculation in the newspapers about ... a professional hit. I think he took a great deal of pride in that. ... he never admitted that he had been involved in it."

David Biro was charged with two counts of first-degree murder, intentional homicide of an unborn child, burglary, and home invasion. He pleaded not guilty.

"You have this horrible crime. And the idea is that it's someone coming from the outside," said McConnell.

"It has to be," Maher commented.

"It has to be," McConnell said. "And in truth it's -- I mean, it's so ironic that it's someone, you know, just a kid from the neighborhood."

No one was more surprised than the Bishop family.

"I was shocked. I was absolutely shocked that a 16-year-old boy could have put a .357 Magnum revolver to the back of a grown man's head and pulled the trigger," said Jeanne.

Even more shocking, David Biro was the son of a family friend.

"I know the Biros," Joyce Bishop said. "David Biro's father worked for my husband at one point. ...I thought, 'Well, that's a mistake I'm sure.'"

"Every year, the Biros would send a Christmas card to my family with a picture of them, the parents and the kids. And I thought, 'Oh, my God. I've seen a picture of this killer," said Jeanne.

But as information trickled out, Jeanne learned more about who that kid on the Christmas card had become.

"What did you find out or hear about him?" Maher asked Jeanne.

"Very disturbing things. That there had been a history of violence. That he had fired out of his window with a BB gun at passersby. That he had lit somebody on fire," she replied.

"David was going down the road of a sociopath," said true-crime writer Gera-Lind Kolarik, who wrote a book about the case.

Kolarik described a deeply disturbed David Biro, who at age 14, tried to poison his family.

"His brother and sister are sitting down at the table for lunch and they drink some milk. And the milk is tainted," she said. "Somebody put wood alcohol into the milk."

Within hours, Biro's parents checked him into a psychiatric hospital for juveniles. But after less than two months, they let him come home, against doctors' recommendations for continued treatment.

"He convinces his father and mother not to let him go back. And they didn't even bother doing any follow-up psychiatric with him," said Kolarik.

"That was it? That's all he ever had?" Maher asked.

"That's it. That's it," she replied.

A hospital assessment written just after Biro left read: "At the time of his leaving the hospital, we believed that he was dangerous to himself or to others."

His parents didn't agree.

"I hold them partially responsible," Jennifer Bishop-Jenkins said. "They knew he was dangerous. And they let him walk around unsupervised with a padlock on his bedroom door. ...behind that padlock, a gun."

"He sought thrills. They gave him a rush," she continued.

Now three years later and awaiting his murder trial, Biro's behavior remained arrogant and cocky.

WBBM news report: "Authorities now believe the Langerts were chosen as victims less because of who they were, than where they lived. ...The motive, they believe, an attempt to commit the perfect crime."

In the fall of 1991, Biro went to trial, with prosecutors using that "perfect crime" motive. Their case was strong: they had Biro's "confession" to his good friend, and all that evidence found in his bedroom, including the murder weapon.

WBBM news report: "It was one of the most sensational murder cases in recent history. ... As the trial begins, many questions remain about the murders."

But in a surprise move, Biro would take the stand.

WBBM news report: "He's accused of two murders, but he's taking the witness stand in his own defense ... 18-year-old David Biro is speaking out in public for the first time."

Biro stuck to his original story - he was just holding the gun for another student who had actually committed the murders. Prosecutors and investigators dismissed the claim outright.

"When I looked at him in the courtroom ... What I saw was a brash, cocky, young man who pretty much believed he was gonna outsmart all of us," said Jeanne.

"Did you ever have any doubt that it was anyone other than David Biro who killed Nancy and Richard?" Maher asked Joyce.

"No. No," she replied.

And neither did the jury. After a two week trial, it took them just a few hours to reach a decision: guilty on all charges.

"I just exhaled in relief," Jeanne said. "I think I felt my jaw loosen and unclench for the first time ... since ... they were murdered."

David Biro received two mandatory life sentences, without the possibility of parole, for murdering Richard and Nancy. The judge also gave him a discretionary life sentence for the death of their unborn child.

"The judge made a speech in which he specifically talked about his age ... he wanted it in the record," Jennifer explained. "He had -- every privilege in his upbringing. That he killed them for sheer entertainment. And, that he was the most deserving of life without parole because he was truly the ... the most dangerous human being."

"Did you all have a collective agreement on the sentencing that you wanted for him?" Maher asked Jeanne.

"Yeah. We wanted the maximum sentence, which was the one he got." She replied. "He'll die on a cold prison floor like Nancy died on a cold basement floor."

The killer was going away for good, and with him went the answers they never got in court.

"We all wished that--part of his sentence would be that he would sit down with us and we could ask him 'Why? How could you do this?'" Jeanne told reporters following the sentencing.

That answer would come, but it would take 22 years, a leap of faith and an incredible change of heart.

"There was only one person who knew the answers to the questions that I had, and that was David Biro himself," said Jeanne.

SEEKING ANSWERS

Long before David Biro's arrest and conviction, Jeanne Bishop was consumed by one extraordinary thought.

"I knew instantly that I didn't want to hate anyone. And I said those words, 'I don't wanna hate anyone,'" she said.

"When Nancy and Richard ... were killed at such a young age, I saw how short life is, how it can be taken from you at any minute," Jeanne continued. "And I thought, 'Oh, my God. I'm wasting this life that God gave me. And what can I do with it?'"

What Jeanne and her sister, Jennifer, did, was transformative.

"You both changed your lives and your livelihood because of this and after this?" Maher noted to Jennifer Bishop-Jenkins.

"That's right," she said.

Both women began to work as outspoken advocates for gun control, and against the death penalty by lobbying and speaking around the country about Nancy and Richard's story.

"I have done a great deal of-- of good work, tryin' to change our violent culture and to help victims of violence," Jennifer explained.

Amazingly, both Jeanne and Jennifer had forgiven David Biro - even though he never admitted he was the killer.

"I think here's what my forgiveness was like. It's like this. I forgive you. And now, I'm wiping you off my hands, like dirt. It is not for you. It's not about you. It's for me," said Jeanne.

"I'm sad for him," Jennifer said. "I'm sad for how cold and and empty -- his life must have been, and I am not going to hate him."

In fact, Jennifer reached out to Biro, inspired by a movement known as restorative justice -- which encourages reconciliation between offender and victims and their families.

"And I said in a very short letter ... 'I would welcome a letter from you if you would like to talk to me.' That's all I said," she said.

That letter, written about 13 years after the murders, was not exactly embraced by Biro the way Jennifer had hoped.

"And he said, 'I'm not gonna confess to this crime, but I'd love to be your pen pal. ...It would be fun.'"

"Those were his words?" Maher asked Jennifer.

"Those were his words," she replied. "And I said -- I wrote back again a very short letter. 'You're clearly not where you need to be. If you ever change your mind, you know where to find me.'"

Meanwhile Jeanne, a well-paid corporate attorney at the time of the murders, made a complete 180-degree turn in her career.

"I became a public defender with Cook County," she told Maher.

The reason? Jeanne says it's because of the way the FBI treated her in those early stages of the investigation - when her human rights worked was linked to the murders.

"So, most people, Jeanne ... they would think that you would run straight to the D.A.'s office and say, 'I'll work for free. Because I wanna catch the bad guy,'" said Maher.

"I understood what it felt like to feel so powerless," Jeanne said. "And what if you were someone who didn't have the resources that I did? They need a good advocate."

Jeanne remained passionate that juveniles with mandatory life sentences, like David Biro, should be behind bars for good.

"You even vowed not to say his name ever," Maher noted to Jeanne.

"And I didn't. For 20 years, I would call him 'the killer,' ' the intruder,' 'the murderer,'" she replied. "Because what I wanted was for Nancy and Richard's name to live ... and for his to die."

But all that changed after she met Marc Osler, a law professor who was on the opposite side of the juvenile justice issue. Osler's mission is to seek reduced sentences and often, clemency.

"She had a moral platform. And that was, 'This life was taken from my family,'" Osler explained. "That he didn't even accept responsibility for what he did. ...And something remarkable happened."

Jeanne may have forgiven Biro, but now she felt called to do more.

"It was really my Christian faith being challenged that caused me to see David as a person, to say his name, to start to pray for him. ...To realize I had to move beyond just forgiving him and wiping him off my hands ... to engaging with him," she said.

Jeanne started by writing her own letter to Nancy's killer in 2012.

"I didn't even think about the outcome as I was writing it. I just knew that I had to," she said. "And I thought, Oh, my gosh. I have been sitting back ... for decades waiting for this young man to apologize to me. I'm gonna go first. I'm gonna say, 'I forgave you a long time ago. ...And if you want me to come see you, I will.'"

Several weeks later, an envelope landed in her work mailbox.

"This is the envelope. There's this name," Jeanne showed Maher.

"Well, that must've stopped you in your tracks," Maher remarked.

"Oh, I froze," said Jeanne.

"To know it's his name and that's his handwriting."

"Right," Jeanne said. "And my heart started hammering because I thought, 'This is it.'"

But she couldn't open it just then. She waited 48 hours, and then passed it to Mark Osler.

"And I opened it. It's 15 to 18 pages," Osler said. "And it was remarkable."

"He said, 'It's good.' And I just sank down in the chair beside him and in relief," said Jeanne.

The letter contained the one piece of information she had been waiting more than two decades for.

"'I think the time has come for me to drop the charade and finally be honest. I am guilty of killing your sister, Nancy, and her husband, Richard. I also want to take this opportunity to express my deepest condolences and apologize to you,'" Jeanne read. "And I started to cry."

"I never thought I would receive that. And to have it was such a burden lifted. It was just like this rock being lifted off of me," Jeanne said. "... for him to understand the magnitude of what he took, and to own it."

Then, the man who murdered her sister agreed to meet to Jeanne, face to face.

"I knew when I was going there to meet him for the first time, to shake his hand, that I was taking the hand that held that gun," Bishop said, "the one that pulled the trigger and fired and ended her life."

Five months later, she made the two-hour drive to Pontiac Correctional Center.

"Well, at first, it was kind of a shock. Because the last time I had seen him, he was this skinny, 16-year-old boy," Jeanne said. "And the person I saw walking through the door was a 40-year-old man."

It would be the first of dozens of visits.

She has written about those experiences in a recent book called "Change of Heart."

"Has he ever told you what happened that night?" Maher asked.

"Oh, the first thing he wanted to do was to tell me. ...This is his explanation. He went to do a burglary, wanted to wait for the homeowners to come home. Wanted to take their wallets and their car," she said. "And they saw him. And that's when he said, 'I knew I-- I just-- I had to finish it.'"

"'I had to finish it'?" Maher asked.

"Yeah. And when he said that word, 'it,' I thought in that first meeting, 'Oh, my God. That 'it' you're talking about is my sister and her husband," Jeanne said. "And that's been part of the reward and blessing of this journey of these visits with him is having my sister and her husband transformed from an 'it' to 'these people.'"

In June of 2012, a few months before Jeanne wrote to Biro, there was a major U.S. Supreme Court decision deeming mandatory life sentences for juveniles tried as adults "cruel and unusual punishment." That means that David Biro could qualify for a reduced sentence, and possibly even be released. Jeanne Bishop is now advocating her sister's killer get a chance ... at a second chance.

"He methodically gunned down two people in your family, even though he knew your sister was pregnant and she was begging for her life," Maher pointed out. "He just doesn't strike me, Jeanne, with all due respect, as the poster child for second chances."

"Does he deserve another chance? Yes. I think he does," said Jeanne.

Asked why, Jeanne said, "Because I think everyone does. I think that it's utter hubris for us to say to any human being ... this one thing you did was so bad that we're gonna freeze it in time forever. All you will ever be is killer. And our punishment for you will be endless, until you die."

But, not everyone agrees.

"It all boils down to one thing," Jennifer said. "Are there some people for whom permanent separation from the rest of society is sadly necessary?"

"Is David Biro that person?" Maher asked.

"Yes he is," said Jennifer.

MOVING FORWARD

"Did you ever think that you would be here ... discussing the possibility of him being resentenced ... and possibly seeing the light of day again?" Maureen Maher asked Joyce Bishop.

"No. No, it-- it never occurred to us," she said.

On Nov. 5, 2015, almost 24 years to the day from when David Biro went on trial for the Langert murders, Nancy's sister, Jennifer, and mother Joyce are back at the same courthouse, as a legal hurdle to Biro's case is argued.

"I think it's an exercise in futility, myself. But -- if he's gonna go down there, I'm gonna go down there," said Joyce.

Biro, who was not in court, has denied "48 Hours"' requests for an interview.

The Supreme Court ruling guarantees Biro will be resentenced on the two mandatory murder convictions, which means that he could get a reduced sentence, freedom, or it could stay the same -- life in prison.

"It's only mandatory sentences that have been struck down by the Supreme Court," Jeanne explained.

There is one legal hitch: because the third sentence for the murder of Nancy's unborn child was not a mandatory life term, it could impact the judge's decision on resentencing.

"So a discretionary sentence, like the one David got for killing the baby on purpose, that could still be in place no matter what happens to the other sentences" said Jeanne.

Biro could be resentenced as early as next year.

"So, as we sit here today ... do you think that he should be released?" Maher asked Jeanne.

"I don't know," she replied. "I've never seen his prison record. I've never read any psychological evaluations of him, either as a 16-year-old or as a 42-year-old. There is so much that I need to know."

And there's a lot more she wants David Biro to know -- no matter what the outcome of his case.

"I mean, one of the most rewarding things about visiting him and telling these ... stories about Nancy and Richard ...He gets to know her better and as he knows her better he says, you know, 'The more I know, the worse I feel about what I did,'" said Jeanne.

"Do you want him to feel worse?" Maher asked.

"I do want him to feel bad about what he did," she replied. "And then that imposes an obligation on him to do good ... no matter where he is, whether he's in prison or out."

"To my last breath will he -- will he ever get that," said Joyce.

Every day, Joyce is reminded of the loss of Nancy and Richard. After the murders, she and her husband moved into that townhouse.

"I think that being here almost makes me feel like, well, Nancy and Richard were here and that's nice, too," she said. "I take comfort in that, that she was here."

Joyce says she cannot forgive, because she cannot forget.

"You know, if he said, 'Forgive me,' I would I say, 'Are you kidding?'" Joyce said. "I come to the part in the Lord's Prayer where it says 'in forgiving my sins as I forgive those who sin against me,' I don't say the second part. I don't forgive. ...not that one."

"Would you be afraid for your safety if David Biro was out?" Maher asked Jennifer.

"Clearly. Clearly, yes. ...The general public is in danger. ...He has not gotten any better. He's still manipulative," she replied. "He never confessed or apologized, admitted to the crime until the ... Supreme Court ruling."

"And you don't see that as a coincidence. You see that as calculation," Maher noted.

"Absolute -- like everything else he does," said Jennifer.

"You know, there's a cost to stepping out like this," Jeanne said of thinking differently. "I know that it has to hurt to all of a sudden feel that we're not on the same side anymore, in a sense."

And that has made keeping a promise made a long time ago challenging ... but not impossible.

"It was the first time I saw her after Nancy and Richard were killed ... as we were holding onto each other," Jennifer recalled. "I remember saying to Jeanne, 'It'll never be just the two of us. It'll always be the three of us.'"

"And it still is?" Maher asked.

"It still is," Jennifer said in tears.

"We agree to disagree. We love each other deeply. And I am proud of my family," Jeanne said. "And I know that they are proud of me."

Despite their ideological differences, Joyce says her daughters have found their own way to work through them.

"The girls can ... have different opinions without being, you know, broken up about it," she told Maher. "Not everybody is the same. We all think differently. But we're all family. And we all love each other."

"Every Palm Sunday after we process up that aisle and we go up into the choir loft ... I'm looking at that procession of children. And every time I do that I cry," said Jeanne.

It's been said there is no one or right way to grieve... It seems the same is true for healing...

"If he has to spend the rest of his life in prison, I'll still be making that drive down I-55 ... I'll still be buzzed through that door. I'll still sit down and visit with him," Jeanne said. "I'm not telling you this is this formula you have to follow. I'm saying that I have to forgive."

David Biro is one of approximately 80 offenders convicted as juveniles awaiting resentencing in Illinois.

Across the country, more than 1,000 offenders may qualify for resentencing under the Supreme Court ruling.

CASE UPDATE

On Dec. 4, 2015, a judge denied Biro's petition to include the discretionary life sentence he received for the intentional homicide of an unborn child in his resentencing hearing.