Return of the humpbacks

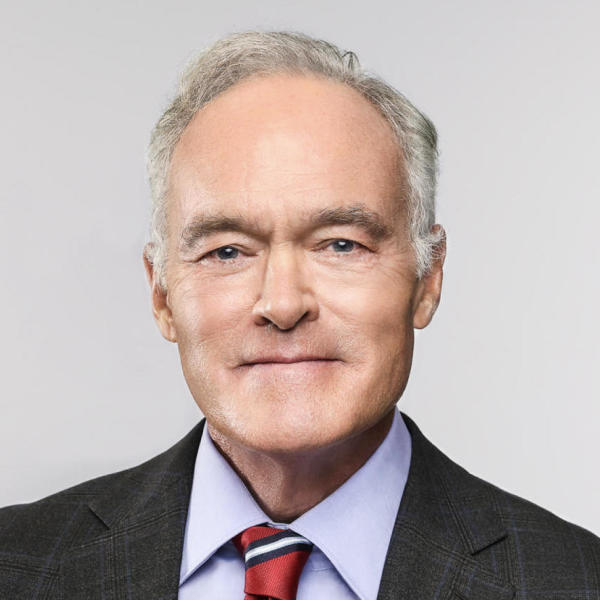

The following script is from "Return of the Humpbacks" which aired on Oct. 20, 2013. The correspondent is Scott Pelley. Robert Anderson and Daniel Ruetenik, producers.

We very nearly lost one of the wonders of the world. The humpback whale was efficiently slaughtered until there were only a few thousand left. But in one of the great success stories in conservation the humpback is making a comeback. It's a good thing too because what we've learned about them lately makes the humpback one of the most fascinating animals ever to grace the Earth.

There are many species of whales and one by one they're coming off the endangered species list. Whale hunting is rare today but there is still a place on the high seas where there's a battle to eliminate the last vestiges of whaling. There we found a man who has risked life and limb to end any threat to whales once and for all.

You're watching the ramming of a Japanese whaling ship by a combative conservationist group, lead by American Paul Watson. He's trying to stop the transfer of a minke whale the Japanese just killed to the factory ship that will cut it up.

Commercial whaling is banned by international agreements. But the Japanese and a few others are still launching harpoons. These scenes were shot for the Animal Plant series "Whale Wars" -- and these scenes were shot by the whalers themselves who say this is evidence that Watson is nothing more than a pirate. The Japanese obtained an international arrest warrant for him. So, for the last year, this conservationist, or pirate, has lived on the world's oceans unable to set foot on land.

Scott Pelley: We are headed out to international waters where Watson lives on a ship beyond the reach of the law. But before he would meet with us, we had to agree that we wouldn't say where we are, or even what ocean this is. Suffice to say it involved several airplanes and many thousands of miles.

Towards the end of that journey, Watson sent this trimaran to pick us up. This boat once set the speed record for circumnavigating the Earth. He named the boat for an actress who's a supporter. But to us it looked more Darth Vader than Brigitte Bardot. Watson came to the Bardot from a floating hideout that we agreed not to show. He is one of the founders of Greenpeace. And now at the age of 62, he calls his new armada: Sea Shepherd.

Paul Watson: The simple fact is this, if the oceans die, we die.

Paul Watson: Sea Shepherd was set up to uphold those international laws and regulations protecting our oceans.

Scott Pelley: But why is that your job? Countries enforce laws. Why are you doing this?

Paul Watson: I just do not see the political will on the part of these governments to do anything.

Scott Pelley: But that makes you a vigilante. You're deciding on your own that you're going to enforce these laws. What gives you the right?

Paul Watson: Because I want to survive. And I want to make sure that my children survive. And I'm not going to sit back and watch the oceans be destroyed because governments don't have the political or economic will to uphold these laws.

The whaling ban makes an exception for research. And the Japanese proclaim that exception in tall letters on their ships. They set their own quotas about 900 minkes, 50 fin whales and 50 humpbacks. These are minkes. And even though the Japanese reserve the right to kill humpbacks, they haven't, according to the International Whaling Commission.

Paul Watson: There is no scientific basis for what they're doing. We have seen them take a whale onto the factory vessel. There's no scientist there. There's nobody measuring anything. They simply cut them up, send them down below, and package them. This is not science. It's bogus.

The International Court of Justice in The Hague will be deciding whether Japan's whaling is really for research or should be stopped. But while the whaling continues, Sea Shepherd fouls the Japanese plan with rope to catch their propellers. The Japanese fire back with water, and ear-splitting sirens. Sea Shepherd throws stink bombs. The Japanese return concussion grenades.

Scott Pelley: You called Sea Shepherd, which you founded, the most aggressive, no-nonsense conservation organization in the world. And you said, quote: "I don't believe in protests. That is far too submissive." What do you mean?

Paul Watson: Well protesting is sort of like, "Please, please, please, don't do that." But they'll do it anyway. But they just ignore you. So, protest is submissive. We're not a protest organization. We're an interventionist organization. We intervene against illegal activities.

But this is what happened recently when Sea Shepherd tried to intervene. The whaler kept coming and sheared the bow off Watson's $2 million boat which eventually sank. No one was seriously hurt. Watson claims he has cut the Japanese catch. Because of these tactics, the same tactics that the Japanese say are illegal.

Scott Pelley: You're in sort of a prison, aren't you?

Paul Watson: Well it's a pretty nice prison. It's you know-- I don't mind being on the ocean. It's a beautiful place and certainly the citizens out here tend to be more peaceful.

Scott Pelley: But when people call your tactics violent, how do you respond to that? I mean, you look at this footage, it looks violent. It's hostile.

Paul Watson: The Japanese are committing violence against living whales. We are not hurting anybody so we're not violent.

This battle is fought in the last place where humpback whales are considered "endangered" by the international agency that decides these things. These "South Pacific" humpbacks feed here in the Antarctic summer then journey north 4,000 miles to mate. This is where much of the research is done around a speck on the map called Rarotonga.

This volcanic island, part of the Cook Islands, is just 21 miles around with 10,000 residents and not a single traffic light. Here we found the human who may know humpbacks best.

Nan Hauser: He's right behind the boat, hello beautiful. He's putting on quite a lovely show for us and you just have to be careful and respect their space.

Scott Pelley: They take up a lot of space.

Nan Hauser is an American marine biologist who intended to come to Rarotonga for one month of research but that was 16 years ago. Now her home and lab are on the side of the volcano and she spends her days eye to eye with her subjects.

Nan Hauser: As you watch them, as you see these massive animals and look at them in the eye and they're looking at you-- and they've never seen what a human looks like before-- and so they're curious about you. And you're curious about them.

Humpbacks are acrobats. Their fins are like wings up to 20 feet long. They cooperate with each other to hunt for the krill and small fish they eat by the tons. We've learned a lot about them in recent years and, some of it we know is because Nan Hauser has risked her life to discover it.

She's part of an international mission to harpoon humpbacks with small satellite transmitters. That rubber boat feels tiny next to an animal 50 feet long that weighs 79,000 pounds.

Nan Hauser: It's very, very dangerous. All they have to do is pick up their tail and give you a good whack and all your bones are broken and your organs are ruptured. So it's very scary. Very, very scary. My heart is pounding.

When they surface to breathe, the transmitter, stuck in their blubber, sends a signal. Now we know humpbacks can travel 10,000 miles a year, that's the world record for a mammal.

Eighty percent of their lives are spent submerged. And this is where Nan Hauser has made some of her most beautiful discoveries.

Nan Hauser: Here we see a male standing on his head, upside down, singing a song. They are motionless and the song bellows out.

The humpback song can be 20 minutes long. And they repeat the same song again and again. Males in one region will all sing the same song the same way. But next year, they'll return with a new composition.

Scott Pelley: So, this is air somehow moving around inside their heads? That's making this sound even though they don't have vocal cords?

Nan Hauser: Correct. It's almost, I think, like taking a balloon full of air and going....

The sound carries for miles. And Hauser believes, its all to mark their territory.

Nan Hauser: They take turns singing, perhaps to say, "My lungs are bigger. I can hold my breath longer. I can sing a more beautiful song. I'm the dominant male. I'm going to sing here so you move away and sing somewhere else."

Scott Pelley: Can you do some of the sounds that you've heard?

Nan Hauser: I think the most common whale sound is kind of a (makes sound). But we get everything. We've even had the laughing monkey, Ee, ee, ee, ee. Creaky doors (makes sound).

Scott Pelley: What are they saying?

Nan Hauser: We don't know.

Scott Pelley: So you speak whale. But you don't understand it.

Nan Hauser: Absolutely.

But she does understand a calf's jaw clapping anger. Hauser captured it when a mother went off to mate and left this calf behind.

Nan Hauser: He does a small clap. Right here.

Scott Pelley: What does it mean?

Nan Hauser: Now I know it means, "I'm upset and I'm gonna have a little bit of a temper tantrum." You can see him. Hear him?

Scott Pelley: He's saying, "Pay attention to me?"

Nan Hauser: Exactly.

Humpbacks give birth to one calf a year. So their comeback has been slow, but steady. Before the whaling ban there were maybe 5,000 left in the world. Now it's estimated there are 80,000. The biggest threats to them these days are collisions with ships and the kind of miles long fishing line that wrapped up this whale.

Nan Hauser: They get wrapped up and then they get held underwater and they need to come up for air otherwise they suffer and they drown.

Hauser hopes that the satellite tags will mark migration routes so that man can steer clear.

History may show we stopped the global slaughter just in the nick of time. Humpbacks are now found in every ocean. Their numbers are back to about 30 percent of what they had been before whaling. It's a sign that a fascinating and beautiful part of the planet is on the mend.