Astronomers find evidence for yet-unseen "Planet Nine"

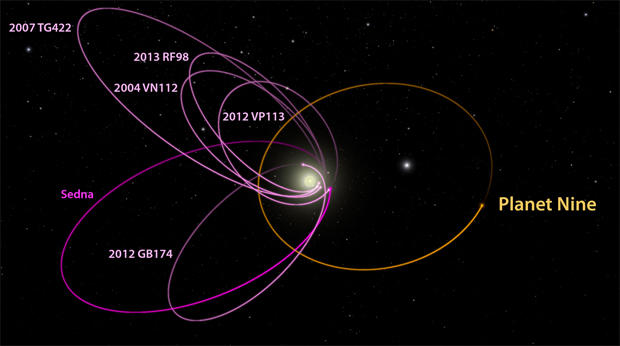

Researchers trying to figure out how a handful of bodies in the remote Kuiper Belt beyond Pluto ended up in unusual, similarly oriented elliptical orbits believe the most likely explanation is the gravitational influence of a hitherto undetected planet with 10 times the mass of Earth that orbits 20 times farther from the sun than Neptune, they announced Wednesday.

California Institute of Technology astronomers Konstantin Batygin, a theoretician, and Mike Brown, discover of multiple dwarf planets in the outer solar system and a vocal proponent of Pluto's demotion from planet-hood, conclude the as-yet-unseen world, which they call "Planet Nine," would take between 10,000 and 20,000 years to complete one trip around the sun.

"It's big enough, and probably reflective enough, that it should be relatively bright," Brown told CBS News in a telephone interview. "We know the orbit, but we don't know where in the orbit it is."

At its closest to the sun, Planet Nine should be visible in large amateur telescopes. If so, Brown said he should have spotted it during earlier surveys of the outer solar system. But he didn't. Given the immensity of the presumed orbit, it will take astronomers time to track it down.

But Brown has no doubt they will eventually find it.

"Even at its most distant from the sun, it's bright enough that it could be seen by at least the biggest telescopes in the world," he said. "So it's not hopeless, this is not something we just have to hypothesize about and you never go out and see it. I think that it will be found within five years now that we know the path in the sky to be searching."

If so, it will be the first new "planet" found since Uranus was discovered in 1781 and Neptune in 1846. Pluto, discovered in 1930, initially was classified as the solar system's ninth planet but it was famously demoted by the International Astronomical Union in 2006.

Brown and Batygin "discovered" Planet Nine using supercomputer simulations and sophisticated mathematical modeling. They describe their findings in the current issue of the Astronomical Journal.

"Although we were initially quite skeptical that this planet could exist, as we continued to investigate its orbit and what it would mean for the outer solar system, we become increasingly convinced that it is out there," Batygin said in a news release describing the research. "For the first time in over 150 years, there is solid evidence that the solar system's planetary census is incomplete."

In 2014, Scott Shepherd and Chad Trujillo, a former student of Brown's, published a paper showing that 13 of the most distant known Kuiper Belt bodies shared unusual orbital orientations and suggested a small, unseen planet might be responsible.

Brown and Batygin then began studying the claim and realized six of the objects listed by Trujillo and Shepherd circled the sun in unusual elliptical orbits that are tilted about 30 degrees with respect to the orbital plane in which Earth and the other planets circle the sun.

On top of that, the orbits seem to "point" in the same direction. And that shouldn't happen by chance.

"The key observation is that there are these Kuiper Belt objects, the most distant objects beyond the orbit of Neptune, the ones that swing out the farthest from the sun so they're the ones that are the least affected by the eight planets that we know, all of those guys suddenly swing off in that one direction," Brown said. "Which is really a bizarre thing to realize."

They really should be completely random around the sky. But to have them all going off like that was quite a shock."Brown and Batygin played with their computer models, adjusting variables to create the observed orbits, but "we couldn't make it work."

Finally, they wondered if the presumed planet might orbit in the opposite direction from the cluster of smaller Kuiper Belt bodies.

"When we first found that, that it's in the opposite direction, we thought that's just wrong, that can't be right," Brown said. "It's fascinating physics the way it works, which we didn't know until we studied it in more detail."

As it turns out, the six objects they were analyzing orbit in what astronomers call "mean-motion resonances" where "they go around the sun some precise number of times for the number of times Planet Nine goes around the sun."

"It's exactly the same as Pluto with Neptune," Brown said. "Pluto goes around (the sun) two times for every three times that Neptune goes around. They cross orbits, but they're never close to each other because Pluto is in this protected resonance orbit."

The Kuiper Belt objects analyzed by Brown and Batygin "are exactly the same way, they're in a protected resonance with Planet Nine which keeps them from being ejected and forces them to stay in the same position in the sky."

Brown is a vocal supporter of the move to demote Pluto from planet-hood and even wrote a book titled "How I Killed Pluto and Why It Had It Coming." But if Planet Nine eventually is found, there won't be any question about its planetary status.

"This would be a real ninth planet," he said in the Caltech news release. "There have only been two true planets discovered since ancient times, and this would be a third. It's a pretty substantial chunk of our solar system that's still out there to be found, which is pretty exciting."