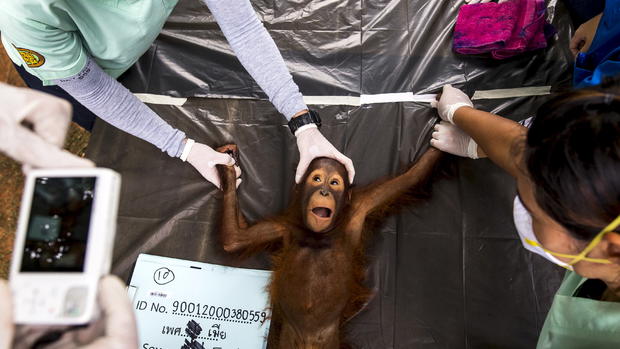

Orangutans released back into the wild in Borneo

KEHJE SEWEN FOREST, Indonesia — Jamur didn’t hesitate as the door of her temporary cramped quarters slid open. In less than a second, the stocky red-haired orangutan was savoring freedom for the first time in nearly two decades.

Her 10-year-old daughter J-lo would join her, along with three more of the endangered great apes.

The long-limbed hirsute primates were the ninth set of Bornean orangutans to be released into natural habitat by the Borneo Orangutan Survival Foundation after years-long rehabilitation from trauma often inflicted by people.

Taken from their sanctuary, Samboja Lestari, to an even remoter spot on the island of Borneo, a journey by road, boat and foot that takes nearly 24 hours, the orangutans bolted from their holding boxes and scaled the nearest trees with astonishing speed and agility.

“Because we love them, we have to let them go, to be free in their habitat,” said Jamartin Sihite, chief executive of the foundation, after all five orangutans had climbed into the tropical forest canopy.

“They have a right to live in their natural state and not with people as pets.”

The release of the five last week marked the 25th anniversary of the foundation and was done in conjunction with government conservation officials. It is part of a herculean effort to prevent orangutans from being wiped out.

The species, known for its gentle temperament and intelligence, lives in the wild only on the Indonesian island of Sumatra and on the island of Borneo, which is divided among Indonesia, Malaysia and Brunei.

Bornean orangutans were this year declared critically endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature due to hunting for their meat, which kills 2,000 to 3,000 a year, and destruction of tropical forests for plantation agriculture. The only other orangutan species, the Sumatran orangutan, is found only on Sumatra and has been critically endangered since 2008.

The conservation group estimates the number of Bornean orangutans has dropped by nearly two-thirds since the early 1970s and will further decline to 47,000 animals by 2025. Some conservationists are even more pessimistic, predicting extinction in the wild within 10 years.

The species is protected in Indonesia and Malaysia but deforestation has dramatically shrunk its habitat, with about 40 percent of Borneo’s forests lost since the early 1970s and another huge swath of forest expected to be converted to plantation agriculture in the next decade.

The Borneo Orangutan Survival Foundation, one of several groups focused on oranguatan conservation, has 60-year concession rights to about 86,000 hectares (212,000 acres) of forest in Borneo that it bought from the government in 2011 for 12.9 billion Indonesian rupiah ($1.5 million at the time), though it says only about 20 to 25 percent of it is suitable orangutan habitat.

“We looked for a place to release them that is very far away from people. We hope that very few people will come to this area in the next 10 or 15 years,” said Sihite.

“Nowadays there is only a few of that kind of area left - far away and really difficult to reach.”

The foundation has released 234 orangutans since 2012. It says 90 percent of those releases are successful.

It typically takes years to return an orangutan to the wild. Finding a suitable location is challenging, as is rehabilitating orangutans so they can survive when returned to natural habitat.

J-lo was born in captivity in 2006 and had to learn survival skills such as nest building, identifying predators and foraging.

Kent, also released last week, was an orphaned 2-year-old suffering from dehydration and severe diarrhea in 1999, when he was rescued from a field.

He spent several years in forest school and graduated to a halfway house, where the apes are less dependent on humans, in preparation for release into the wild, which happened in 2014. But injuries from fights with another male meant he needed another stint in Samboja Lestari.

“We don’t have a choice,” said Sihite. “We have to do this to save the orangutan.”