"Prometheus": Designing the future

(CBS News) In the new science fiction film "Prometheus," genetic re-engineering is central to the characters' quest for the origins of human life. Likewise, "Prometheus" shares more than a little DNA with the 1979 film "Alien," a seminal horror classic that has already spawned several sequels.

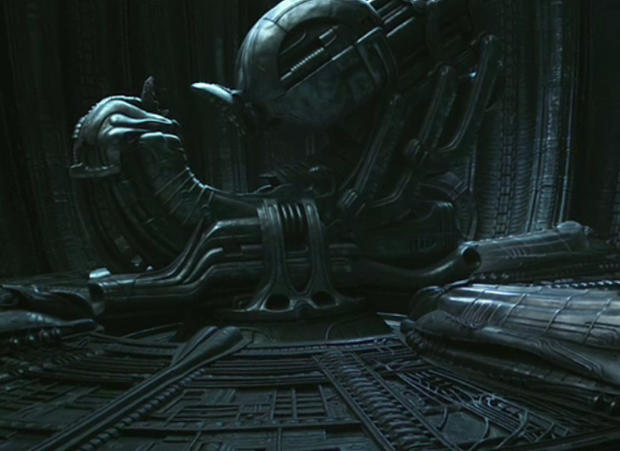

That film set new standards for shock effects while revelling in designs that were both grungily claustrophobic (the aging space tug Nostromo, which is invaded by a nasty, transformative creature) and mesmerizingly beautiful (the bio-mechanical design of the alien architecture, and of the creature itself).

"Prometheus" returns us to the universe of "Alien" but several decades before, yet it is not in the strictest sense a prequel (or at least, some narrative glitches prevent it from directly setting up the first film). The new adventure centers on the discovery on Earth of ancient pictograms that point to another world where mankind may find its origin. Taking the signs as an invitation, scientists embark on an expedition aboard a massive interstellar craft named Prometheus, but find upon arrival they're not exactly welcome.

Creating both the titular craft and the (barely) habitable world that is its destination was the responsibility of production designer Arthur Max, a frequent collaborator of director Ridley Scott, who has earned two Academy Award nominations. A New York native whose earliest experiences were in stage lighting for rock concerts (including the 1969 Woodstock Festival and Pink Floyd), Max eventually worked in commercials and then features with directors David Fincher ("Se7en," "Panic Room") and Scott ("Gladiator," "Black Hawk Down," "Kingdom of Heaven," "American Gangster" and "Robin Hood," among others).

One of the mysteries of "Alien" - a perfectly self-contained horror film - was the origin of the derelict craft found by the Nostromo's crew. That find became a launching point for the new film's narrative (set in the late 21st century) which extrapolates the first film's groundbreaking work by artist H.R. Giger. His designs and creatures melded mechanics and the organic into a compelling evocation of a species and civilization truly alien to humanity.

Having worked in both period and contemporary milieus, Max told CBS News that a film's designs must be grounded in an appreciable reality for an audience to accept the more fantastical elements - to be both relevant and inspirational.

"I think the history of film has always been about that - it uses the technology it has to expand what's possible in the imagination of the audience," Max said. "And we tried to do that in 'Prometheus' more so than I think in any other project, because with science fiction there really are no boundaries."

He says production designers who ignore credibility in their sets do so at their peril: "People are not that immune to their perceptions when they feel that there's something artificial about it. It doesn't ring true. So you apply those rules to science fiction, just as well as you do in any other period, whether it's ancient or modern."

Max said he felt a little daunted at first because he had never done science fiction, but said, "There was a point where I never did ancient Rome, I never did medieval Jerusalem, I never did Somalia. . . ."

He took the approach that Scott wanted to do something that in an indirect way pointed to where his "Alien" began. "So in a way it was designing in reverse, and reconstructing what he and Giger had done originally. And the other [approach] was to introduce our own logic to the storytelling."

Max said initial demands on design were for ambience and mood, amassing and producing imagery that either passed or failed ("How long did it survive on the wall?"). The inspirations for the look of the film (Scott's first shot on digital, and in 3-D) varied, from the space art of Chesley Bonestell and Robert McCall to classical sculpture. The film boasts what Max calls "a very eclectic design, overlaying high technology and very archaic discoveries of an unknown culture that's probably many thousands of years ahead of us."

Most essential to the film's believability was Prometheus itself, Weyland Industries' state-of-the-art expeditionary vessel. Unlike the Nostromo, which was a third-class, dirty workhorse of the Weyland fleet, the Prometheus is, as Max puts it, "a Cadillac of the skies."

Prometheus was designed so that it could go anywhere and deal with any terrain. "We always knew we would be landing in a hostile environment, worse than you can imagine on Earth - toxic atmosphere, unstable terrain," said Max. "We designed the Prometheus to deal with anything; it has a very complex landing system and levelling system, and it had every technology you could want for space exploration and exploitation."

Much was extrapolated from technologies currently in use or being developed by NASA and the European Space Agency. Max also consulted with the Jet Propulsion Laboratories in California and with futurists in fields of biology, medicine, surgery and theology, and visited an experimental robotic medical trauma unit being developed for the military.

"It gave us a certain amount of technical information, but then you also layer that with a kind of style which very often [portrays] another aspect of the story," he said.

Filling five stages at England's Pinewood Studios (including the "007 Stage," already one of the world's largest but which had to be expanded), the sets for "Prometheus" included a two-tiered ship's bridge with a wrap-around glass cockpit; and the luxurious quarters for Weyland executive Vickers (Charlize Theron) which feature a virtual wallscreen environment, designer furnishings, and a robotic medical pod for emergency surgeries.

Also constructed was the massive alien compound referred to as the Pyramid, with corridors opening onto ever-more mysterious chambers.

Although pre-production had planned on shooting exteriors in the deserts of Morocco, the Arab Spring made shooting in North Africa less tenable, and so the "Prometheus" crew settled onto the desolate, primordial landscape of Iceland.

If anything, the film's themes are closer to Scott's "Blade Runner" than to "Alien" - the power of creating (and taking) life, the dominance of technology, and the power of a corporation to change society at the cost of science and morality. If corporations really are people, then in "Prometheus" it's a person with a monster bursting out of its chest.

"Prometheus" marks Max's eighth collaboration with Scott. "Every project we do is a new genre and territory, so we approached it in the same way. When we did 'Gladiator,' for example, we watched the work that preceded us - because most people's perceptions of ancient Rome are based on the films they've watched - so you have to sort of speak to that in terms of scale. And that's the same problem we faced with 'Prometheus.' There's been a lot of science fiction, so you look at what's gone before you in a broad way and then you take what interests you and try to give it something of your own."