Portion control may be all in the mind, studies suggest

(CBS/AP) It's no secret that eating big portions at restaurants contributes to America's obesity epidemic. But according to a new study, that doesn't mean Americans want to eat more when they eat out.

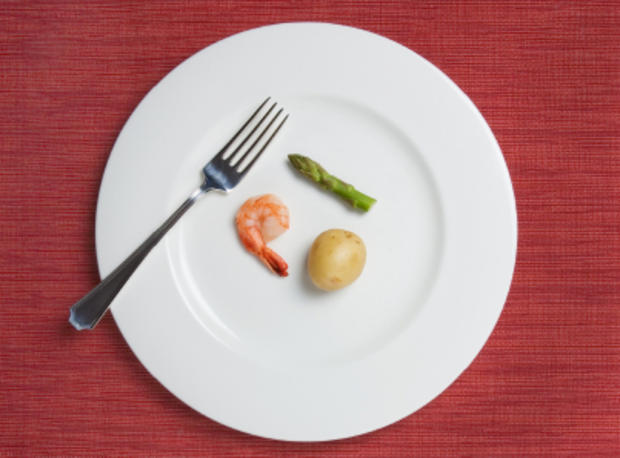

PICTURES: Fighting flab? Mayo Clinic guide to portion size might help

Researchers went to a fast-food Chinese restaurant at Duke University and found up to a third of diners jumped at the offer of a half-size of the usual heaping pile of rice or noodles - even when the smaller amount cost the same. The researchers hope their findings can lead others to tap into the psychology of eating to find new ways to trim portions without diners feeling cheated.

Big fork could be key to small waistline, study saysPICTURES: Oops! 8 ways parents make kids fat

"The small Coke now is what used to be a large 15 years ago," study author and psychologist Janet Schwartz, a marketing professor at Tulane University. "We should ask people what portion size they want," instead of large being the default.

What about just asking for a doggie bag? That works for Americans who have the willpower to stop themselves from eating, but most research suggests we clean the plate that's in front of us. Americans tend to rely on visual cues about how much food is left, shoveling it in before the stomach-to-brain signal of "hey wait, I'm getting full" sensation arrives.

For the study, published in the Feb. 2012 issue of Health Affairs, researchers tested a different approach: Could we limit our temptation if we focus not on the tastiest reason we visited a restaurant - the entree - but on the side dishes? After all, Schwartz says, restaurants can pile on calorie-dense starches like rice or pasta or fries because they're very inexpensive and fill to plate to make it look like you're getting a good deal.

Researchers observed the Chinese food franchise and in the serving line, customers pick the rice or noodles first. A standard serving is a whopping 10 ounces, about 400 calories even before the entree touches your plate, says Schwartz.

In a series of experiments, servers asked 970 customers after their initial rice or noodle order: "Would you like a half-order to save 200 calories?" Customers who said yes didn't order a higher-calorie entree to compensate and when researchers weighed leftovers, they found that diners threw away the same amount of food as those who refused or weren't offered the half-order option.

A 25-cent discount didn't spur more takers, nor did adding calorie labels so people could calculate for themselves, the researchers said, concluding the up-front offer made the difference.

Anywhere from 14 percent to 33 percent chose the reduced portions, depending on the day and the mix of customers.

Restaurants are taking notice, says prominent food-science researcher Brian Wansink of Cornell University. His own tests found children were satisfied with about half the fries in their Happy Meal long before McDonald's cut back on size and calories, last year.

Don't call this down-sizing, but let's call it "right-sizing," says co-author and Duke University behavioral economist Dan Ariely. Right-size suggests it's a good portion, not a cut, he says.

"We'll be seeing some very creative ways of down-sizing in the next couple of years," predicts Wansink, author of Mindless Eating: Why We Eat More Than We Think.

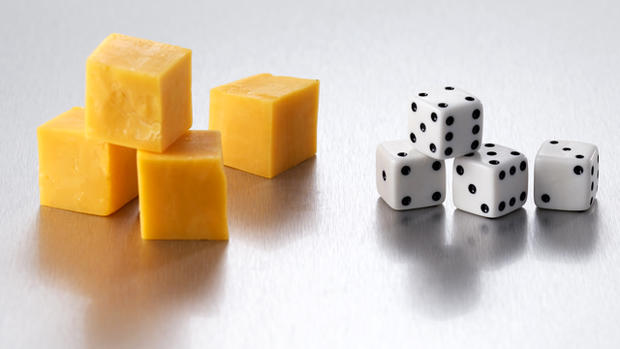

Even 200 fewer calories can add up over time. And other tricks can trim portions without people noticing, both dining out or at home. Cornell's Wansink found people served 18 percent more pasta with marinara sauce onto a red plate than a white one - and 18 percent more pasta alfredo onto a white plate.

A stark contrast "makes you think twice before you throw on another scoop," explains Wansink. Wansink's family bought dark dinner plates to supplement their white ones, because people tend to overeat white starches more than veggies.

Wansink's other research has found:

- Switching from 11-inch plates to 10-inch ones makes people take less food, and waste less food, because the smaller plate makes a normal serving look more satisfying.

- People think they're drinking more from a tall skinny glass than a short wide one even if both hold the same volume, a finding Wansink says is widely practiced in bars.

- Kids shouldn't eat from the adult bowls. Six-year-olds serve themselves 44 percent more food in an 18-ounce bowl than a 12-ounce bowl.

Restaurants are starting to get the message that at least some customers want to eat more sensibly. Applebees, for example, has introduced a line of meals under 550 calories, including such things as steak. And a National Restaurant Association survey found smaller-portion entrees, "mini-meals" for adults and kids, and bite-size desserts made a new trend list.

It's all consumer demand, says association nutrition director Joy Dubost: More diners now are "requesting the healthier options and paying attention to their calories."

Nearly 40 percent of U.S. adults are obese, along with 17 percent of children ages 2 to 19, according to the CDC. Being obese or overweight raises your risk for heart disease, type 2 diabetes, blood pressure or cholesterol problems, stroke, and cancer.