Pillars of commerce

Banks today are as common as coffee shops and equally imposing. It's kind of surprising there are buildings at all, when your bank is in The Cloud.

It wasn't always this way.

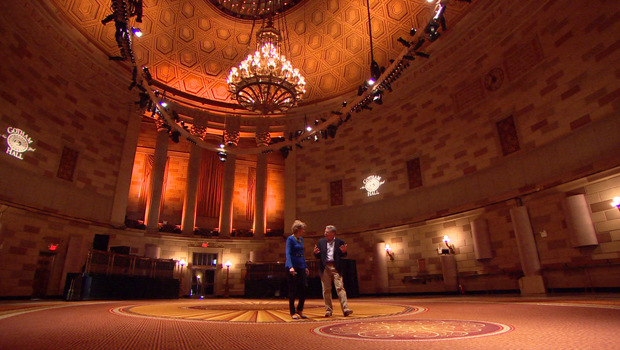

The bank used to be synonymous with "imposing," even "monumental." Like Gotham Hall, in New York City, which is now a venue for weddings and special occasions. Built in 1924, with columns 40 feet high and five feet in diameter made of solid limestone, it used to be the Greenwich Savings Bank.

"This was the last great classical bank built in New York City, and probably in the United States," architect and historian Charles Belfoure told correspondent Jane Pauley.

"You'd go into the tiniest podunk town in America, and you'd find this really ornate classical bank. Even as a kid, I knew it was a fancy building and that it was a special building, just like a church would be."

Like a church, the coffered ceiling and soaring pillars were intended to inspire awe and reverence ... for money.

The vault was a showpiece, built to be seen, admired and trusted, and might be ten percent of the cost of the entire building.

"They wanted to show the depositor that their money was absolutely safe," said Belfoure.

But it was an illusion. They could, and often did.

"Throughout America's financial history, hundreds and hundreds of banks failed, and the depositors would lose every nickel they had," said Belfoure.

"They'd go to the bank one morning, the doors would be shut. And there would be a note posted saying, 'The bank is either temporarily closed or permanently closed.' And that was it.

And yet, Bowery Savings Bank built its majestic shrine in downtown Manhattan only a year after the Great Panic of 1893, when hundreds of banks failed.

"Why did they keep spending money on building astonishing banks if everyone is remembering the history of Grandma, who lost everything?" asked Pauley.

"Well, they wanted them to forget," said Belfoure.

And they did.

At the dawn of the Roaring Twenties, Bowery built a skyscraper atop America's first "branch" bank.

One critic called it "a castle in the clouds, brought to Earth."

A few years later, the economy came crashing to Earth.

"Americans blamed bankers for the Depression," said Belfoure.

But after World War II, with the economy booming and optimism rising, banks were back with a new message: Transparency.

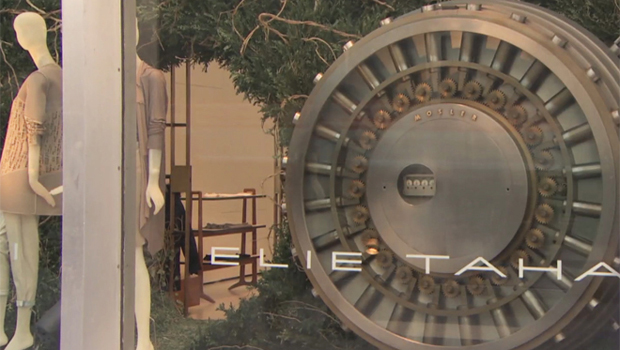

In 1954 architect Gordon Bunshaft designed a totally transparent building for Manufacturer's Trust.

Belfoure said, "It almost seemed like people inside would be more honest, you know, about what they were doing."

The vault sat right in the window not ten feet from Fifth Avenue.

Today, the bank is gone but the 30-ton vault is still there in the window, like a jeweled accessory, at Elie Tahari's design store ... while the escalators that once conveyed customers to the banking floor now carry shoppers through the flagship store of Joe Fresh.

Ironic, but fitting, that an iconic bank has become a retail store, says Belfoure: "It's basically a financial supermarket.

No need to impress. Sit down. Feel right at home. "Homey is a big word," he said. "They're more like, you know, your living room."

And the vault? "Nobody cares about the vault," said Belfoure. "There's no need to crack a vault or rob a bank when you can do it with a computer."

And the castles of yesteryear? Some have been literally brought to Earth, but some survive -- and can still dress to impress.

For more info:

- Gotham Hall, 1356 Broadway, New York

- Capitale, 130 Bowery, New York

- Cipriani 42nd Street, New York

- charlesbelfoure.com

- "Monuments to Money: The Architecture of American Banks" by Charles Belfoure (McFarland)

- elietahari.com

- Joe Fresh