NASA's Messenger probe crashes onto Mercury

NASA's hardy Messenger spacecraft, out of fuel at the end of a remarkably successful 11-year mission, ended its life with a bang Thursday, smashing into the hellish surface of Mercury at some 8,700 miles per hour and blasting out a new crater in the process.

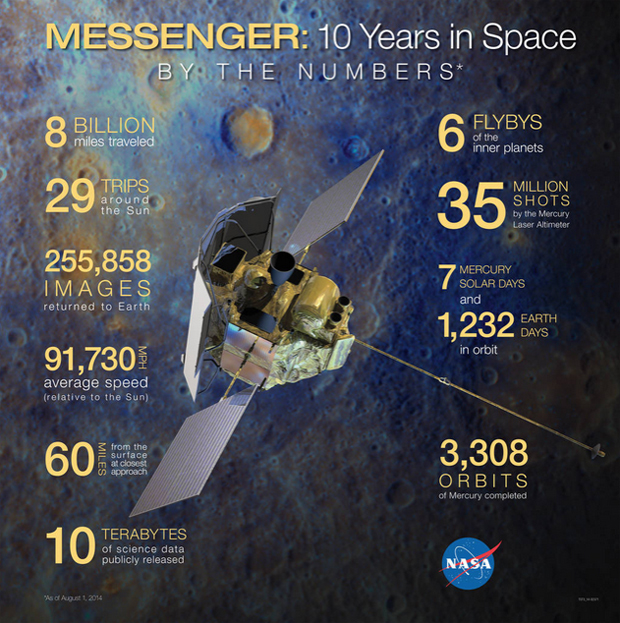

Launched in 2004, Messenger has spent the past four years in orbit around the closest planet to the sun -- a first in the history of planetary exploration -- working behind a sunshade to endure temperatures higher than 600 degrees Fahrenheit while beaming back more than 10 terabytes of data from a suite of sophisticated instruments.

"In those four years, it's taken an amazing array of data," said Jim Green, NASA's director of planetary science. "The spacecraft and the instruments have worked virtually flawlessly over those four years. Now the data is on Earth, we have it now, and we're going to continue to make wonderful discoveries with it."

Built by the Applied Physics Laboratory at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, the Mercury Surface, Space Environment, Geo-chemistry and Ranging mission -- Messenger -- finally ran out of the propellant needed to maintain a stable orbit and resist trajectory perturbations caused by sun's gravity.

Engineers came up with a clever plan to release pressurized helium, normally used to push propellant to the spacecraft's thrusters, to provide a final bit of lift, delaying the inevitable to collect a bit more scientific data.

But the helium, like the fuel, was finally exhausted and gravity took over, quickly pulling the craft down.

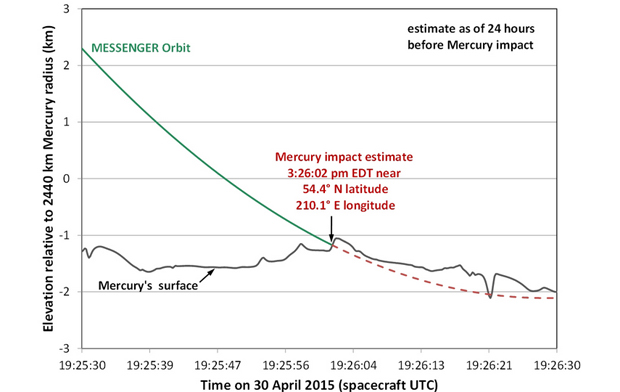

Impact on the far side of Mercury, out of contact with Earth and at a velocity of some 8,700 mph, is believed to have occurred at 3:26 p.m. EDT (GMT-4). Scientists and engineers confirmed the mission was over at 3:40 p.m. when they attempted to contact the spacecraft. There was no response.

"Today we bid a fond farewell to one of the most resilient and accomplished spacecraft ever to have explored our neighboring planets," Sean Solomon, Messenger's principal investigator, said in a statement. "Our craft set a record for planetary flybys, spent more than four years in orbit about the planet closest to the sun, and survived both punishing heat and extreme doses of radiation."

Solomon praised Messenger's "resourceful and committed team of engineers, mission operators, scientists and managers" for a mission that "surpassed all expectations and delivered a stunningly long list of discoveries that have changed our views not only of one of Earth's sibling planets but of the entire inner solar system."

Along with mapping Mercury's surface in exquisite detail, Messenger measured electric currents flowing down magnetic field lines and back out again, detected bursts of energetic electrons accelerated by some unknown mechanism, characterized a small-but-dynamic magnetosphere and measured seasonal variations in the planet's "exosphere," a tenuous atmosphere that stretches out behind Mercury like the tail of a comet.

Messenger also showed Mercury has contracted over the life of the solar system, shrinking by more than four miles due to interior cooling. The planet harbors an offset magnetic field, has widespread volcanic deposits and unusual "shallows" where surface material has been lost.

Solomon said Messenger's top two discoveries were confirmation of extensive water ice deposits in shadowed craters at the planet's poles and the discovery that volatile elements like potassium, sulfur, chlorine and sodium -- easily lost at high temperatures -- are still in place.

"Prior to our mission, all of the theories, almost all, for how Mercury was assembled to end up as dense as it is predicted that Mercury would be deficient in all the elements that are easily removed at high temperatures, the volatile elements," he said.

"Mercury is as volatile rich as Mars, and as volatile rich as Earth. It was not predicted to be so. ... The ideas for how the inner planets got assembled, and how the building blocks of planetary materials were delivered to the inner solar system and survived the process of planetary accretion are all being changed by Messenger's results."

Engineers planned to stay in contact with Messenger until 10 to 15 minutes before impact, collecting data until the very last moment when the spacecraft was expected to swing out of view on the far side of the planet as viewed from Earth.

The impact was expected to gouge out a crater 50 feet across, completely destroying the spacecraft in the process. The crater will not be visible to Earth-based instruments, but a spacecraft built by the European Space Agency and Japan should reach Mercury in 2024 and its instruments will search for Messenger's final resting place. Not for sentimental reasons, but to learn more about how "weathering" works on the innermost planet.

"On Mercury, some of the brightest deposits on the surface are young impact craters, and we know there are a variety of processes that serve to darken the surface, collectively known as space weathering, that operate on the moon and other airless bodies," Solomon said. "On Mercury, they seem to operate faster."

The weathering is caused by the constant impacts of micrometeoroids and energetic ions and electrons, but how fast the processes work is not known.

"So having an impact crater, even a small one, whose origin date is precisely known will be an important benchmark," Solomon said.

The ESA-Japanese BepiColombo is expected to search for the crater and "if they can make measurements of it, they'll know precisely how long that region has been exposed to space and that will be an important study," Solomon said.

And a final success for Messenger.