Millions on food stamps facing benefits cuts

(MoneyWatch) It is late October, so Adrianne Flowers is out of money to buy food for her family. That is no surprise. Feeding five kids is expensive, and the roughly $600 in food stamps she gets from the federal government never lasts the whole month. "I'm barely making it," said the 31-year-old Washington, D.C., resident and single mother.

Starting Friday, the money is likely to run out even quicker.

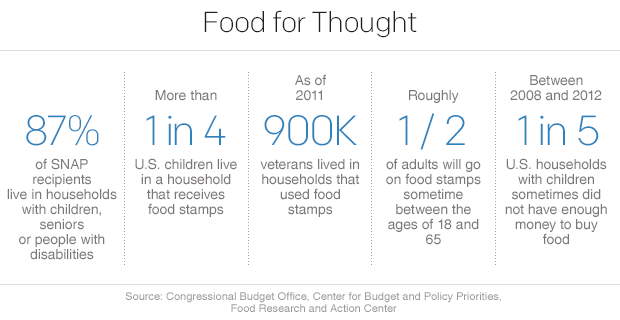

That is when Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP, benefits are set to fall for more than 47 million lower-income people -- 1 in 7 Americans -- most of whom live in households with children, seniors or people with disabilities. Barring congressional intervention, the maximum payment for a family of four will shrink from $668 a month to $632, or $432 over the course of a year.

That amounts to 21 meals per month, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. The cuts will leave participants in the program, better known as food stamps, with an average of $1.40 to spend on each meal. The amount people get could sink even more if Congress makes deeper cuts later this year when House and Senate lawmakers try to hammer out a farm bill.

The Nov. 1 benefit cuts "will be close to catastrophic for many people," said Ross Fraser, a spokesman for Feeding America, the nation's largest domestic hunger-relief charity, which estimates that this week's SNAP reduction will result in a loss of nearly 2 billion meals for poor families next year.

Food stamps are the government's biggest nutrition-assistance program for low-income people and, along with federal unemployment benefits, a key support system for the most vulnerable Americans. More than three-quarters of households getting food stamps include a child, elderly person or someone with a disability. Some 83 percent of families are at or below the official poverty line (roughly $11,500 for an individual and $23,500 for a family of four).

Not surprisingly, participation in SNAP has soared during the epic downturn and ongoing job slump that followed the housing crash, with an additional 21 million people added to the rolls since 2008. Today, more than 1 in 4 U.S. children live in a home that gets food stamps.

SNAP gets a lot of use: Statistics show that roughly half of all U.S. children go on food stamps sometime during their childhood; half of all adults are on them sometime between the ages of 18 and 65. The USDA estimates that, as of last year, nearly 15 percent of American families, or 18 million households, lacked enough food at least some of the time to ensure that all family members could stay healthy.

Another group with lots of members in SNAP: Veterans. U.S. Census Bureau data show that, in 2011, some 900,000 former U.S. military personnel lived in households that used food stamps.

Inflicting hunger

The average SNAP recipient receives about $133 a month in benefits, while the typical family gets $278. Benefits are means-tested, meaning that poorer households receive larger benefits (The formula used to calculate payments assumes that families will spend 30 percent of their net income on food.)

With the vast majority of SNAP beneficiaries already destitute, the diminished assistance would hurt in the best of times. But the Great Recession has thrown millions more people into poverty, including a growing segment of working poor. Experts say the food stamp cuts will spread hunger in the U.S., undermine public health and tax food banks around the country struggling to cope with the upsurge in poverty.

"The cuts are going to make millions of people hungry," said Jim Weill, president of the Food Research and Action Center, a not-for-profit public policy firm focused on ending hunger in the U.S. "It's going to send people into a charitable system that's already overwhelmed and screaming for help itself. And it will make life harder and worse for millions of children, seniors, veterans and people with disabilities."

Another possible casualty -- everyone else. The left-leaning Center for Budget and Policy Priorities, a Washington think-tank, says that the November benefit cuts will curtail the flow of money into every U.S. state, in some cases by hundreds of millions of dollars.

The concern? Economists have found that every dollar of SNAP spending generates roughly $1.70 in local economic activity. The USDA has calculated that food stamps generate an even bigger bang for the buck. So pinching food stamp recipients also will squeeze the broader U.S. economy. Among other effects, that could dent revenues for the nearly 250,000 groceries and supermarkets around the country that accept SNAP payments, potentially affecting everyone from store workers and truck drivers delivering food to consumers, as food sellers raise prices to offset the loss of revenue.

Meanwhile, research suggests that reducing food aid could not only increase hunger, but also undermine public health. In a six-year study, Children's HealthWatch, a nonpartisan pediatric research center, recently found that young children in families that got SNAP benefits were at significantly lower risk of being underweight, which is linked with poor nutrition, and of developmental delays. That jibes with research by Northwestern University economist Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach. She has found that since food stamps were introduced in the 1960s, women in the program have seen a reduction in low-weight births and a decrease in infant mortality.

Families that get food stamps are also able to eat more healthfully and are less likely to skip doctor's visits to pay for food, housing and other basic needs. "Increasing SNAP benefit levels improves family diet quality and children's health," the authors of the Children's HealthWatch report wrote.

Will work for food

SNAP costs about $80 billion a year, which amounts to roughly 2 percent of the federal budget. It is paid for entirely by the federal government, although administrative costs are shared by states. Congress reauthorizes funding for the program every five years.

Payments are scheduled to decline this week because Congress three years ago voted to reverse a temporary increase in benefits made under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, a 2009 law passed to bolster the sagging economy.

As the economy was melting down, lawmakers at the time lifted monthly SNAP payments by $20 to $24 per month. Economists say this is an effective way to stimulate growth because the poor must spend almost all of their money just to get by. That, in turn, funnels money into the economy, creating a "multiplier" effect as food benefits spent in a grocery store generate revenue for other businesses.

The size of SNAP cuts will vary by state. California faces the largest spending reduction, at $457 million, which will affect more than 4 million people. Other states with large populations of SNAP recipients expected to see big cuts include Florida, Michigan, New York and Texas. Some states have already sought to trim the rolls by imposing new eligibility requirements for food stamps. In Ohio, for example, able-bodied people must work or get job training at least 20 hours a week to qualify for SNAP.

For critics of food stamps, including those who express concern about certain kinds of government spending, such measures are necessary to shrink the federal deficit and encourage SNAP beneficiaries to work. Hostility to the program, especially among some conservatives, has long made it a target. In the early 1980s, for example, Congress moved to slim down SNAP costs by basing benefits on people's gross, not net, income and by limiting income tax deductions for people, among other measures.

The reality, however, is that many people who get food stamps are working. Well over half of SNAP recipients have jobs, according to the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities. More than 80 percent of beneficiaries find employment within a year of starting to collect payments.

With the economy no longer in free-fall and SNAP participation leveling off, analysts also do not expect the program to drive up the deficit. The Congressional Budget Office projects federal spending on food stamps to fall over the next five years as the economy strengthens.

Watering the milk

Most SNAP recipients run out of food stamps by the third week of the month, Fraser said. Parents often skip meals to ensure children are fed and use other means to make ends meet. "I had a mother tell me recently that her children loved milk, so she was secretly watering it down to stretch it," he said.

"It's always, 'I've got to get something for my kids.' They're not coming in and asking for snacks or this or that. They're asking for things like milk and cereal," added Margarette Purvis, CEO of the Food Bank for New York City, which provides food to more than 1.5 million local residents. "They're saying that they don't have anything for breakfast. People are looking for something they can feed their children right now."

Families, particularly single mothers, rely heavily on food kitchens, mobile food pantries, faith-based organizations and other charitable groups when their food stamps run out. Flowers leans on her church and Bread for the City, a Washington, D.C., group that provides food, clothing, medical care and other services for lower-income people.

But that, too, worries, anti-hunger specialists. People in the field say food banks across the country are already at their limit in the help they can offer people. Resources are always tight, and they have been stretched to bursting by the recession and anemic recovery.

"While this work is fueled by love, it can't be sustained by it," said Purvis, a veteran hunger activist who nevertheless expressed shock that Congress would reduce food aid. "You need cash and you need resources. And right now there is none."

As usual with large socioeconomic problems requiring public policy solutions, any remedies in principle lie in Washington. That may be bad news for SNAP recipients. Although some Democrats in Congress have attacked the Nov. 1 rollback in benefits, the Democratic-controlled Senate in June approved legislation that included $4.5 billion in SNAP cuts. House Republicans envision far more draconian cuts, passing a bill last month that would cut funding for the program by $40 billion over 10 years.

When it comes to America's hungry, it seems, political leaders who can't agree on anything can agree on this: The poor can make do with less.

For her part, Flowers has not given up hope that elected officials will help her keep food on the table. "They found a solution to the government shutdown," she said, "so I hope they can find a solution to this."