Life insurance industry under ingestivation

The following is a script from “Not Paid” which aired on April 17, 2016, and was rebroadcast on Aug. 14, 2016. Lesley Stahl is the correspondent. Rich Bonin, producer.

When you take out a life insurance policy, you pay premiums in the expectation that when you die your spouse or your children will receive the benefit. But, as we reported in April, audits of the nation’s leading insurance companies have uncovered a systematic, industry-wide practice of not paying significant numbers of beneficiaries.

At the time of our broadcast, 25 of the nation’s biggest life insurance companies had agreed to pay more than $7.5 billion in back-death benefits. However, about 35 insurance companies still had not settled and remained under investigation for not paying when the beneficiary was unaware there was a policy, something that is not at all uncommon.

Kevin McCarty: The beneficiary never comes forward because he or she doesn’t know the policy exists.

But the companies know, says Kevin McCarty, the insurance commissioner of Florida, who led the national task force investigating the industry. And the companies don’t pay, he says, unless a beneficiary makes a claim.

Kevin McCarty: And what we found is that companies have actual knowledge in their files that people have died, yet they have neglected to initiate an investigation and pay the claim.

Lesley Stahl: So in other words, life insurance companies are failing to pay out death benefits when they know the person is dead, and they’re claiming they don’t know.

Kevin McCarty: In many cases, that has been exactly what we have found.

Lesley Stahl: When you found that, what went on inside you?

Kevin McCarty: My first instinct was of course is unleash the hounds of hell -- let’s go after them, and expose them for the unconscionable, indefensible behavior that was going on.

He says some of the policies are worth more than a million dollars. But most are valued at less than $10,000.

As a result of the audits, Joseph Bigony of West Virginia recently got a long-overdue payment of more than $5,000 from his sister’s policy.

Joseph Bigony: I was the administrator of her estate when she died in June of 1990, and we didn’t know anything about this at all.

Jeff Atwater: You’re talking about millions of policies.

Lesley Stahl: Millions?

Jeff Atwater: Hundreds of thousands of policies that we’re dealing with just here in Florida.

Jeff Atwater is the chief financial officer of Florida in charge of regulating the state’s insurance industry.

Jeff Atwater: You can assume from what we have found that the policies that should have paid out in the 60s, in the 70s, in the 80s, in the 90s were never paid.

Lesley Stahl: And you’re saying it’s part of their plan?

Jeff Atwater: After all we’ve looked at, Lesley, it would be hard to imagine. This is not a small dollar amount. These are billions of dollars that now stay in the investment accounts of these insurance companies rather than return money to those families.

Lesley Stahl: Tell us some of the big names.

Jeff Atwater: It would be all the large brand names that you’re familiar with: John Hancock, MetLife, Prudential. Many of these companies have sat down with us and made right.

No one disputes that the insurers pay out on policies when the beneficiary files a proper claim.

But says Kevin McCarty of Florida, many of the companies routinely and deliberately disregarded evidence in their own files that the policyholders had died.

Unless someone filed a claim, he says, the companies would cancel the policy and keep the death benefit for themselves.

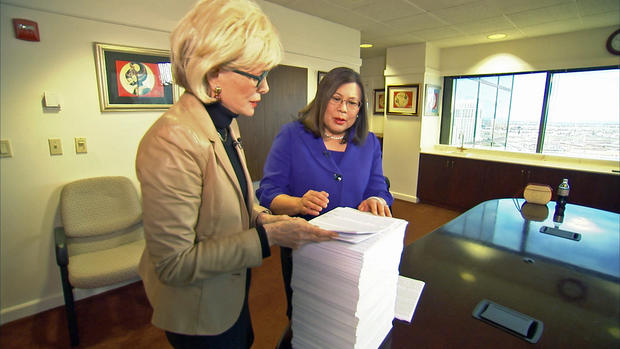

Kevin McCarty: Here’s a life insurance policy that’s issued in Florida in January 2002. The insurer died in April of 2008. We actually have in the insurance company’s file, a copy, a scanned copy, of the death certificate.

Kevin McCarty: And the accompanying envelope which displayed the spouse’s return address.

Lesley Stahl: With the spouse’s address on it.

Kevin McCarty: It’s right here.

Lesley Stahl: Let me see.

Kevin McCarty: Less than one month after the death the policy was terminated for non-payment.

Industry lobbyists - like this one at a recent hearing in Florida -- argue that the burden falls on the beneficiaries.

Lobbyist: We all enter into contracts every day and if you sign that contract, you’re obligated to know what’s in it.

Lesley Stahl: The companies argue that in the policies that these people signed, it says - black and white - that they have to make the claim and show up with a copy or the policy itself. “And if they don’t do that, we don’t have an obligation.”

Kevin McCarty: But Florida law says something too. And you have to look at it not just in terms of the contract, but to your responsibilities under the Florida insurance code. And I’m here to say that you have a responsibility to investigate a claim if you know someone has died. And if you have a letter that says you’re deceased, you have actual knowledge the person has died.

Insurance companies are regulated separately by each state and he says similar laws are on the books across the country.

State regulators first got wind of the insurance industry practice from Jim Hartley and Jeff Drubner who run a technology and auditing company called Verus Financial. Based on an insider tip in 2006, Drubner, employing techniques he had used as an FBI agent, combed through insurance company data and discovered that the insurers were routinely using the Social Security Death Master File - which is a constantly-updated list of people who have died in the United States.

Lesley Stahl: What was the significance to you that they were using the Death Master File for something?

Jeff Drubner: I knew at that point that they knew because if you have--

Lesley Stahl: They knew who was alive and dead, is what you’re saying?

Jeff Drubner: Yeah, because they know who they’ve insured and if they have a list of everybody that’s passed away. I knew that they knew.

Lesley Stahl: What was the next step?

Jim Hartley: The next step was to speak to the states. There wasn’t one treasurer, one controller or one attorney general who didn’t have a reaction that this shouldn’t be allowed to happen and we have to fix it.

Drubner went on to discover that most insurance companies used the Death Master File only when it was to their advantage: to cut off annuity or retirement payments once the policyholder died. But they didn’t then notify the life insurance side of the company.

Kevin McCarty: We have actual cases, Lesley, where a policyholder had both an annuity and a life policy. And they terminated the annuity, and of course they knew the person was dead, so they-- so--

Lesley Stahl: Claimed over here that they didn’t know he was dead?

Kevin McCarty: Lesley, when we went in and looked at the memos, the right side told the left side and the other side said--

Lesley Stahl: And you saw it in the audits? You’d just see it-

Kevin McCarty: We saw it in the audits.

Something else they saw in the audits related to “whole life” insurance policies -- that in addition to a death benefit build up a cash nest egg, like a 401K.

What they found is that when a beneficiary did not come forward, the company continued to pay themselves premiums out of the dead person’s nest egg.

In this $20,000 policy, for instance, the nest egg was drained down more than $9,000 to zero...after the person had died.

California Controller Betty Yee says that kind of siphoning off was widespread in cases where beneficiaries did not come forward.

Betty Yee: How can you not be outraged by this?

She says that in about a third of the cases there was evidence of death in the file.

Betty Yee: Here we have a policyholder.

Lesley Stahl: Is this the actual file that you saw with the word “deceased” in large, large unmistakable letters--

Betty Yee: Yes, yes, “deceased” with the date of death.

Lesley Stahl: And still they didn’t-- they didn’t stop paying themselves.

Betty Yee: No, no, and you would’ve thought with that kind of indication, a next step would be to confirm that by looking at the Death Master File and beginning the claims process with the family member.

Lesley Stahl: And they didn’t.

Betty Yee: They didn’t.

When the cash was all used up the companies cancelled the policy. Under the law they’re allowed to pay themselves premiums using their customer’s accumulated cash while they’re alive. Florida’s McCarty says the law was originally intended as a way to protect consumers.

Kevin McCarty: For instance, if you have a life policy and you lose your job and you can’t make your premium payment, they will take some of the cash value that’s built up in your policy and pay the premium. Which is great for consumer protection.

But in this situation, after they died...

Kevin McCarty: I think it’s tantamount to stealing when you know in your books and records the person is dead and you drain the policy. Now if you think about that, if you would have explained that trying to sell that policy at the beginning.

Lesley Stahl: At the beginning.

Kevin McCarty: You’re sitting in your kitchen and saying, you know, you’ve got all these symbols of security and financial stability and we’re going to be there for you with your family in their grief, but they say, “Oh, by the way. If you stick that policy in a shoe box and stick it in your closet, not only are we not going to look for you, but we’re gonna to take all the cash value in it, and...

Lesley Stahl: Give it back to the company.

Kevin McCarty: Give it back to the company. And leave your beneficiary with nothing. Here, sign here.

The 25 insurance companies that have settled with the states admitted no wrongdoing, but agreed to pay out more than $7.5 billion - either directly to the unpaid beneficiaries or to the states, which then try to find the beneficiaries by phone...

Woman: We have received some funds from an insurance company that’s in your name.

Or online...

PSA: Thousands of Oklahomans are owed money from life insurance policies.

None of the life insurance companies we contacted would give us an interview, but speaking on their behalf, the industry trade association, the American Council of Life Insurers, told us quote: “most life insurers are going well beyond what the law requires to identify policy owners who have died and left unclaimed benefits.”

Ken Miller, the treasurer of Oklahoma, says there are still about 35 insurance companies that have not settled and some are fighting tooth and nail. At stake, he says, is up to $3 billion more in unclaimed benefits nationwide.

Lesley Stahl: Who’s fighting the hardest?

Ken Miller: Kemper is the main one.

Kemper, a Chicago-based insurance company, has been pushing for legislation around the country that would bar the states from forcing Kemper to go back and search for unpaid beneficiaries.

When we called Kemper, they referred us to Steve Weisbart of the Insurance Information Institute -- who says making companies like Kemper pay now would be unfair.

Steve Weisbart: If we can say, “Do something today that you didn’t expect to do and didn’t plan to do and didn’t collect money to do 30 years ago,” what else can we say today that they should be doing retroactively. It’s potentially an open door.

Lesley Stahl: A slippery slope is what you’re saying?

Steve Weisbart: A slippery slope.

Kemper has argued in court filings that it’s never used the Death Master File to identify deceased policyholders and that finding and paying their beneficiaries now would result in “a substantial financial loss...” and require the company to “...substantially alter (its) business practices.”

Ken Miller: If your model is built upon the fact that you’re not going to pay a dead person’s loved ones for a policy that they’ve completely paid in full, to me that’s just a bad policy.

An Oklahoma woman, Sherry Sanders, didn’t know about her husband’s policy until about a year ago, when - because of a settlement, she got a check worth $22,000. We asked Oklahoma Treasurer Miller how much an insurance company can make by holding on to the $22,000.

Ken Miller: Well, Lesley, now you’ve hit on something that’s the most important issue. And that’s the time value of money. Because that’s what this is all about. This is about money. That $22,000 invested for 50 years at an eight percent return becomes $1.2 million.

Lesley Stahl: That the company gets because it sat there?

Ken Miller: And that’s just one small policy. If you expand that over all the policies that’s just due to my state, it’s a tremendous amount of money, billions and billions of dollars.

The American Council of Life Insurers says that the industry has paid out more than $600 billion in death benefits over the last 10 years - so the companies are doing a good job.

Ken Miller: I don’t think we should pat ‘em on the back for doing what they’re supposed to do.

Lesley Stahl: But the companies say that this is only 1 percent of the life insurance policies.

Ken Miller: Then why fight it? If it’s so inconsequential, if it’s such a small amount-- then why be spending your reputation to not pay dead people’s loved ones money that’s rightfully due them.

Since our broadcast first aired, 11 additional life insurance companies holding about a billion dollars in unclaimed policies have either agreed to pay back death benefits or have entered into settlement talks to do so. Kemper is not one of those companies. And in states like California, Florida and Illinois it continues to fight audits and legislation requiring insurance companies to pay off unclaimed policies.