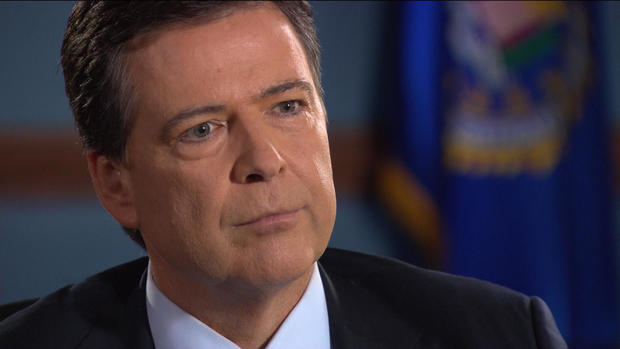

James Comey in 2014: "You cannot trust people in power"

- The FBI director is given a 10-year term so they can lead in a way that's "not influenced by the political winds," James Comey told 60 Minutes in 2014.

- Comey also said the founding fathers "divided power among three branches, to set interest against interest" because people in power cannot be trusted.

This past week, the president decided to fire the director of the FBI just as James Comey was leading the investigation into whether associates of President Trump colluded with Russia to tip the election.

Comey, known for his integrity, angered both parties. Democrats say he cost Hillary Clinton the presidency when he announced, just before Election Day, that the FBI was investigating whether she mishandled classified information in newly discovered emails.

Last Monday, President Trump called the Russia investigation a "taxpayer-funded charade." The next day, Mr. Trump's Justice Department recommended that Comey be fired. James Comey gave us his first in-depth interview as director in 2014. He was one year into a 10-year term. And Donald Trump had not yet announced his candidacy, but even back then the concerns on Comey's mind, were what America is debating today.

James Comey: I believe that Americans should be deeply skeptical of government power. You cannot trust people in power. The founders knew that. That's why they divided power among three branches, to set interest against interest.

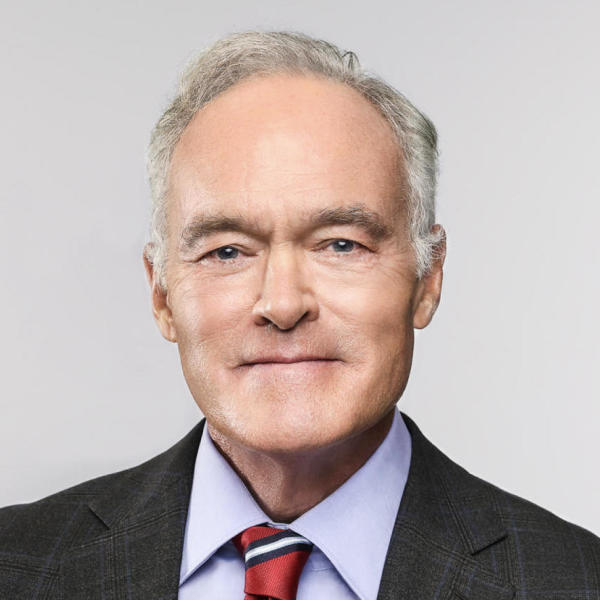

Scott Pelley: With regard to privacy and civil liberties, what guarantee are you willing to give to the American people?

James Comey: The promise I've tried to honor my entire career, that the rule of law and the design of the founders, right, the oversight of courts and the oversight of Congress, will be at the heart of what the FBI does. The way you'd want it to be.

"I believe that Americans should be deeply skeptical of government power. You cannot trust people in power."

Scott Pelley: Does the FBI gather electronic surveillance that is then passed to the National Security Agency?

James Comey: That's one of those things I don't know whether I can talk about that in an open setting so I-- I better not start to go down that road with you.

Scott Pelley: You have said, quote, "We shouldn't be doing anything that we can't explain." But these programs are top secret. The American people can't see them and you can't explain them.

James Comey: Right. We can't explain everything to everybody or the bad guys will find out what our capabilities are, both nations and individuals. What I mean is I need to be able to explain it either directly to the American people or to their elected representatives, which we do extensively with Congress.

Scott Pelley: There is no surveillance without court order?

James Comey: By the FBI? No. We don't do electronic surveillance without a court order.

Scott Pelley: You know that some people are going to roll their eyes when they hear that?

James Comey: Yeah, but we cannot read your emails or listen to your calls without going to a federal judge, making a showing of probable cause that you are a terrorist, an agent of a foreign power, or a serious criminal of some sort, and get permission for a limited period of time to intercept those communications. It is an extremely burdensome process. And I like it that way.

That's a principle over which James Comey is willing to sacrifice his career. He proved it in 2004 when he was deputy attorney general. Comey was asked to reauthorize a package of top secret, warrantless, surveillance targeting foreign terrorists. But Comey told us significant aspects of the massive program were not lawful. He wouldn't be specific because it's still top secret.

Scott Pelley: This was not something you were willing to stand for?

James Comey: No, I was the deputy attorney general of the United States. We were not going to authorize, reauthorize or participate in activities that did not have a lawful basis.

At the time, Comey was in charge at the Justice Department because Attorney General John Ashcroft was in intensive care with near-fatal pancreatitis. When Comey refused to sign off, the president's Chief of Staff Andy Card headed to the hospital to get Ashcroft's OK.

Scott Pelley: You got in a car with lights and siren and raced to the hospital to beat the president's chief of staff there?

James Comey: Yep, raced over there, ran up the stairs, got there first.

Scott Pelley: What did you tell the attorney general, lying in his hospital bed?

James Comey: Not much, because he was very, very bad off. I tried to see whether he was oriented as to place and time. And it was clear to me that he wasn't. I tried to have him understand what this was about. And it wasn't clear to me that he understood what I was saying. So I sat down to wait.

Scott Pelley: To wait for Andy Card, the president's chief of staff?

James Comey: Yeah. Then White House Counsel Gonzales.

Scott Pelley: They spoke to Attorney General Ashcroft and said that the program should be reauthorized and you were there to argue that it should not be. How did it end?

James Comey: With the attorney general surprising me, shocking me by pushing himself up on his elbows, and in very strong terms articulating the merits of the matter. And then saying but-- but that doesn't matter because I'm not the attorney general. And then he turned to me and pointed and said there's the attorney general. And then he fell back. And they turned and left.

Scott Pelley: You'd won the day?

James Comey: Yeah, I didn't feel that way.

Scott Pelley: How did you feel?

James Comey: Probably a little sick. And a little sense of unreality that this was happening.

The next day, some in the White House tried to force the authorization through a different way. So Comey wrote a letter of resignation to the president, calling the situation "apocalyptic" and "fundamentally wrong." He left the letter on his desk and he and FBI Director Robert Mueller went to the White House to resign.

James Comey: Yeah. We stood there together, waiting to go meet the President, looking out at the Rose Garden, both of us knowing this was our last time there, and the end of our government careers.

Scott Pelley: Wasn't it your responsibility to support the president?

James Comey: No. Not my responsibility. I took an oath to support and defend the Constitution of the United States.

Scott Pelley: This was something the president wanted to go forward with. And you were standing in front of the president of the United States telling him he shouldn't do it. And if he did, you'd quit. Do I have that right?

James Comey: Yeah, I don't think I expressly threatened to quit at any point. But that was understood.

President Bush was persuaded.

Scott Pelley: The program that we've discussed, as I understand it, was in fact reauthorized, but in a modified form? It was made to conform to the law in your estimation?

James Comey: Yes.

Scott Pelley: Help me understand the principle at stake here that caused you to write a letter of resignation, to rush to the attorney general's bedside, to tell the President that he couldn't have what he wanted, and to face down the President's chief of staff. What was it that motivated that?

James Comey: The rule of law. Simple as that.

He's been a federal prosecutor most of his career. In 2003, President Bush appointed him deputy attorney general, number two at the Justice Department. But after two years he left for private industry, telling his wife that it was her turn to do what she wanted. Then the phone rang.

James Comey: The attorney general called and asked me if I was willing to be interviewed for FBI director. And the truth is I told him I didn't think so, that I thought it was too much for my family. But that I would sleep on it and call him back in the morning. And so I went to bed that night convinced I was going to call him back and say no.

Scott Pelley: What happened?

James Comey: I woke up. And my amazing wife was gone. And I found her down in the kitchen on the computer, looking at homes in the DC area, which was a clue. And she said I've known you since you were 19. This is who you are. This is what you love. You've got to say yes. And then she paused and said but they're not going to pick you anyway, so just go down there and do you best. And then we'll have no regrets.

Scott Pelley: At least you would have tried.

James Comey: Right.

Scott Pelley: So you met with the president.

James Comey: I did.

Scott Pelley: What happened?

James Comey: Had to give my wife some bad news: that her confidence in them not picking me was misplaced.

Scott Pelley: What did the president say about what goes through his mind when picking an FBI. director?

James Comey: The president's view is that it's-- has to be someone who is competent and independent to protect this institution.

Scott Pelley: You say that the president wanted independence from his FBI director. But the Justice Department answers to the president.

James Comey: It does. But it has to maintain a sense of independence from the political forces. I don't mean that as-- as a pejorative term. But the political forces in the executive branch. And that's why the director is given a 10-year term, so that it is guaranteed that you'll spend presidential administrations to make sure that you're leading it in a way that's not influenced by the political winds.

We talked with Comey, who is 6-foot-8, at his headquarters in Washington. In technology, the cutting edge cuts both ways and Comey told us he's worried now that Apple and Google have the power to upend the rule of law. Until now, a judge could order those companies to unlock a criminal suspect's phone. But their new software makes it impossible for them to crack a code set by the user.

James Comey: The notion that we would market devices that would allow someone to place themselves beyond the law, troubles me a lot. As a country, I don't know why we would want to put people beyond the law. That is, sell cars with trunks that couldn't ever be opened by law enforcement with a court order, or sell an apartment that could never be entered even by law enforcement. Would you want to live in that neighborhood? This is a similar concern. The notion that people have devices, again, that with court orders, based on a showing of probable cause in a case involving kidnapping or child exploitation or terrorism, we could never open that phone? My sense is that we've gone too far when we've gone there.

The FBI is spending a lot of its time online these days. This is a new cybercrime headquarters that the public hasn't seen before. We agreed to keep the location secret.

They call it cywatch, and it pulls in resources from the CIA, NSA and others. Comey's agents are running down leads in the theft of JPMorgan's data. Often in cases like that the suspects are overseas. So the trouble is, in cyberspace, where do you put the handcuffs?

James Comey: It's too easy for those criminals to think that I can sit in my basement halfway around the world and steal everything that matters to an American. And it's a freebie, because I'm so far away.

Scott Pelley: A lot of those people are operating in countries where they're not going to be given up to the United States?

James Comey: Yes.

Scott Pelley: Russia, China, elsewhere.

James Comey: Yep, a challenge that we face, so we try to approach that two ways is one, work with all foreign nations to try and have them understand that it's in nobody's interested to have criminal thugs in your country; and second, again to look to lay hands on them if they leave those safe havens to impose a real cost on them. We want them looking over their shoulders when they're sitting at the keyboard.

Scott Pelley: When the phone rings in the middle of the night, which I'm sure it does, what's your first thought?

James Comey: Something has blown up. Yeah.

Scott Pelley: It's terrorism that concerns you the most, even after what we said about cybercrime?

James Comey: Yeah, I think that's right because it's terrorism that can have the most horrific, immediate impact on innocent people.

James Comey has kept a memo on his desk to remind him of unchecked government power. Marked "secret," it's a 1963 request from FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, titled "Martin Luther King Junior, Security Matter- Communist." Hoover requests authority for technical surveillance of King. The approval is signed by Attorney General Robert Kennedy.

"The lesson is the importance of never becoming untethered to oversight and accountability."

Scott Pelley: And there was no court order. It was the signature of the FBI director and the signature of the attorney general?

James Comey: Yep. And then open-ended. No time limit. No space restriction. No review. No oversight.

Scott Pelley: And given the threats in the world today, wouldn't that make your job so much easier?

James Comey: In a sense, but in the-- in the-- also in a sense, we would give up so much that makes sure that we're rooted in the rule of law, that I'd never want to make that trade.

Some of the worst of the FBI's history is in its investigation of Dr. King. So, on Comey's orders, FBI Academy instructors now bring new agents here to talk about values lost in the pursuit of the man who became a monument.

Woman: Character, courage, collaboration, competence. We have to be able to call on those tools in our toolbox to be able to make sure that we are correcting some of the things that happened in the past.

Scott Pelley: What's the lesson?

James Comey: The lesson is the importance of never becoming untethered to oversight and accountability. I want all of my new special agents and intelligence analysts to understand that portion of the FBI's history the FBI's interaction with Dr. King and draw from it an understanding of the dangers of falling in love with our own rectitude. And the importance of being immersed in that design of the founders with oversight by the courts and Congress so that we don't fall in love with our own view of things.

Produced by Robert Anderson and Pat Milton. Aaron Weisz, associate producer.