Is recycling worth it?

NEW YORK Justin Ramirez is a recycler. The 23-year-old New Yorker says he goes through the extra effort of sorting his trash to decrease the amount of landfill and save resources. "I don't see the progress I'm making, but it makes me feel better, that I'm doing my part," he said.

His 25-year-old brother, Eddie Ramirez, feels a little differently. "I'm not against recycling, I just think it's a matter of convenience," he says. He'll throw something out in a recycling bin if he comes across one, but said he heard somewhere only 5 percent of waste produced in the country is from residential homes, making him feel he has little influence. "For me, it's kind of like, why are we doing it?"

Both opinions are commonly held beliefs. The verdict on recycling has been up in the air for decades; its critics claiming its effects have been exaggerated, its advocates claiming it's critical to our environment. But at the end of the day, is it worthwhile to spend that extra effort separating glass from plastics?

The "5 percent" statistic Eddie raises is a real one cited by experts - an overwhelming majority of waste produced in the country annually is industrial, leaving regular folks to have limited influence in the overall flow of waste.

"Recycling is what it is, but it's not saving the earth," says Samantha MacBride, an assistant professor at Baruch College in New York City, and the author of "Recycling Reconsidered."

No wonder the Onion ran the headline in 1997: "EPA: Recycling Eliminated More Than 50 Million Tons of Guilt In '96"

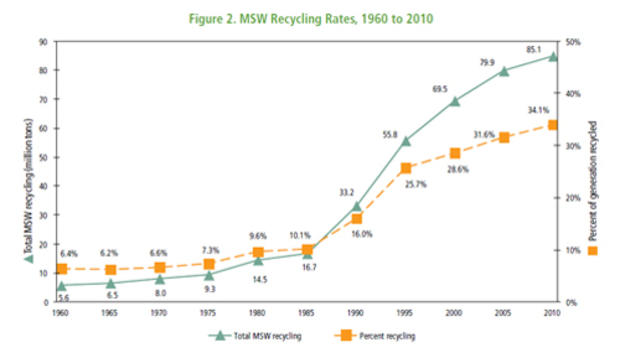

Still, Americans continue to recycle; of the 250 million tons of trash thrown out of homes in 2010, 85 million was diverted from landfills - a rate higher than ever before. According to the EPA, that's comparable to removing the emissions of 33 million passenger cars.

Ron Gonen, hired to lead New York City's recycling efforts in 2012, says recycling is making a comeback. Gonen says new technology makes separating bottles and boxes critical to the environment.

"It's very important for New Yorkers to understand that recycling is not just good for the environment, but it's equally good for their pocket books," says the deputy commissioner of recycling and sustainability.

Gonen works for a city of notoriously lazy recyclers: Only 15 percent of New York City's municipal waste is diverted from landfills, compared to the about 34 percent of waste diverted nationwide. But the deputy commissioner of recycling and sustainability says new programs implemented by the city in just the past year have raised that rate "a few percentage points," saving the city $30 million a year, Gonen says. The goal is to bring up that rate to 30 percent by 2017, saving the city $60 million annually.

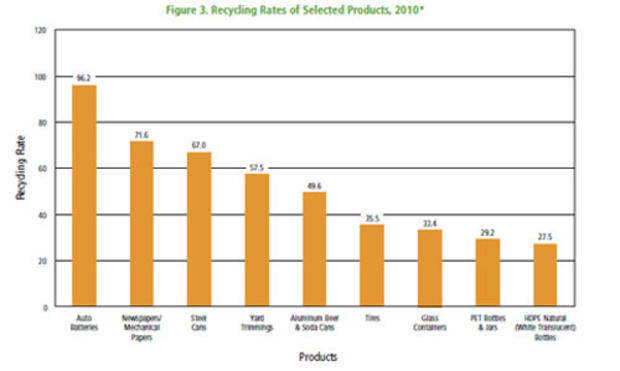

To weigh the pros and cons of recycling, it's important to realize the cost and efficiency of recycling varies from material to material.

According to 2010 data by the EPA, tossed auto batteries are most likely to actually get recycled, followed by paper. Of all the auto batteries thrown out in 2010, 96 percent were recovered; paper, meanwhile, was recovered at a rate of about 72 percent. The materials least likely to be melted and reused were plastic: PET (Polyethylene terephthalate) bottles and jars had a recycling rate of 29.2 percent, white translucent bottles a rate of 27.5 percent.

For New York City, paper is among the easiest materials to recycle. Pratt Industries, which runs a 40-acre paper mill in Staten Island that's employed by New York City, makes a business out of recycling paper. It takes 12 hours for paper dumped by sanitation trucks to be turned into a pizza box, a process recycling division general manager Hank Levin says is "virtually, fairly simple." They also make recycled paper and sell it to clients like Home Depot.

Gonen says it generates revenue for the city.

"NYC earns a floor of $10 per ton for recycled paper, which means that we save $86 per ton in landfill disposal savings and earn a minimum of $10 per ton," Gonen said.

Every morning sanitation trucks stop by the mill after their route and dump their paper collections into what's called a "pit," where the paper is broken down by hot water (360 degrees Fahrenheit) and starch. Machinery then sifts out any contaminants in a sorting facility (they take out five tons of plastic each day).

In many cases, private companies say they find it's not more expensive to go green, either. Brian Wilson, director of operations at Star Pizza Boxes, says they work with Pratt because it just happened to be a good program for them -- its location in Staten Island helps them keep shipping costs down. Being environmentally friendly is just a perk.

"The pizza market is driven on price. We offer the best price. Not everyone is as environmentally conscious as others, and it's a good selling point to add that," Wilson said, adding that the company "save[d] 180,982 trees" from being cut down in 2012.

Plastics are another story.

Plastic items are labeled with the number one to seven depending on the polymer of the material, but even two plastic items of the same number can't necessarily be recycled together. A tray labeled No. 1 (polymer: PET) can't be recycled in the same pot as a bottle labeled No. 1 because they melt at different temperatures. It's more expensive to collect and sort. For this reason, many cities limit the amount of plastics they take in; New York City, for example, only takes jugs and bottles - although they can be thrown into the same bin as glass items. The city says it's working with federal regulators to change the numbering system so it's clearer for residents.

"Plastic shopping bags are very challenging for us. Foam cups, foam plates, very challenging for us," Gonen says. "We don't have the technology to actually separate it from either the waste or the recycling stream."

The beverage and bottle industries aren't particularly helpful in this department. The production of plastic only increased, MacBride says, when they popularized bottled water in the late 1990s.

"If you go anywhere and you simply want some water, you have to buy it," MacBride said. "That was not consumer driven. It was seen as a new marketing opportunity by the beverage industry. It's ridiculous. Before we had a great system - you used a tap and you got a nice glass of water."

The environment would probably be better off with less plastic, but MacBride argues there's not much even the most tree-hugging, earth-loving individuals can do about it.

"The thing is you can choose to live this ultra-virtuous life and consume as little as possible, and it's very difficult," she said. "I challenge anyone to go one day without using plastic."

But what would happen, hypothetically, if the country was full of model citizens who recycled perfectly? It depends on who you ask.

"Even if everyone is America was perfect at recycling everything, it wouldn't make a dent in the overall flow in the waste materials," MacBride says.

Gonen, however, says a difference would be felt - on a local level, at least.

"It would make a noticeable difference for our environment because there are so many people in New York, as well as just a tremendous amount of visitors to New York," he said. "The amount of trees, oil that we would save from recycling ... and it would be saving tens of millions of dollars in disposal fees."

Then what's the verdict? Most experts would agree country has much bigger waste problems that can't be solved by recycling alone. That said, recycling isn't bad and will likely only get better as technology develops. In a lot of ways, it helps companies and governments save some money in the long run.

Even with all her skepticism, MacBride says people shouldn't get discouraged.

"I think to be an adult and think, 'ok, my recycling is not really solving the problem' -- you shouldn't despair over that. Just look at it as a piece of scientific information," she said. "People get very emotionally upset when they hear these statistics and think they should throw everything in the trash. To me that's a response a kid would have, not an adult."