Iran nuclear deal endangered if Donald Trump seeks to renegotiate its terms

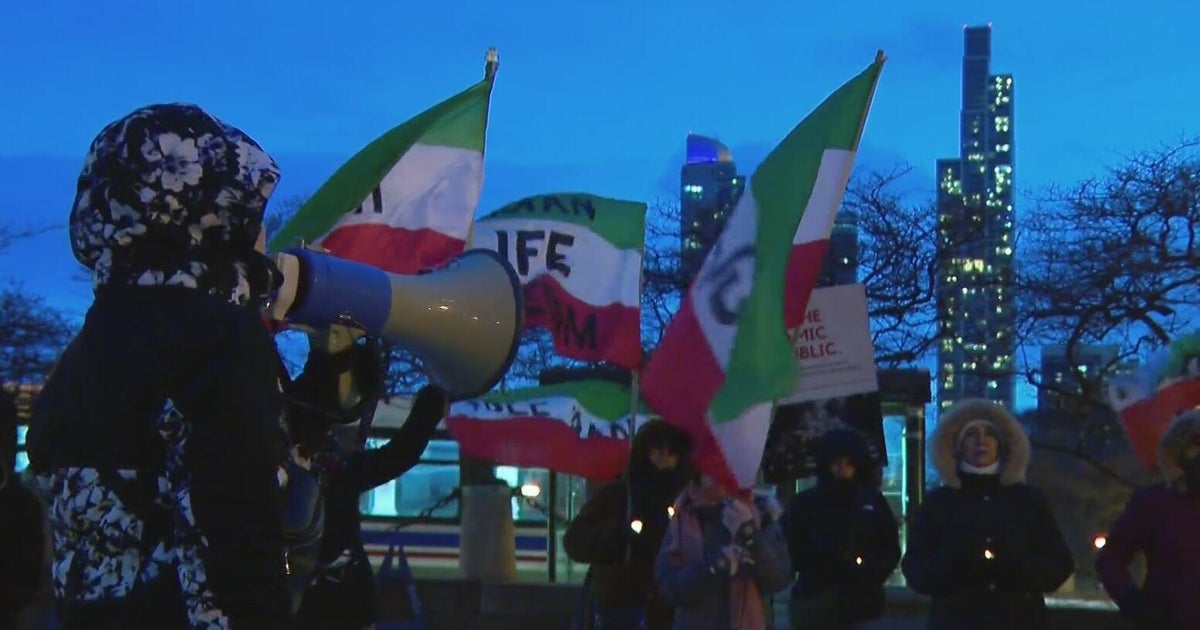

WASHINGTON -- Donald Trump isn’t going to rip up the Iran nuclear deal on day one as president, but his vows to renegotiate the terms and increase enforcement could imperil an agreement that has put off the threat of Tehran developing atomic weapons. Emboldened Republican lawmakers are already considering ways to test Iran’s resolve to live up to the deal.

As a candidate, Trump issued a variety of statements about last year’s pact. He called it “stupid,” a “lopsided disgrace” and the “worst deal ever negotiated,” railing against its time-limited restrictions on Iran’s enrichment of uranium and other nuclear activity, and exaggerating the scale of U.S. concessions.

Trump said that he doesn’t want to simply tear up the agreement. Instead, he spoke of reopening the diplomacy and declared that unlike President Obama’s diplomats, he would have been prepared to walk away from talks.

Trump’s exact plans are vague, however, and a renegotiation would be difficult. Iran has little incentive to open talks over a deal it is satisfied with. And none of the other countries in the seven-nation accord has expressed interest in picking apart an understanding that took more than a decade of stop-and-go diplomacy and almost two full years of negotiation to complete.

As Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, has said: If the U.S. tears up the agreement, “we will light it on fire.” President Hassan Rouhani said this week no country could simply change what was agreed, pointing to a U.N. Security Council resolution that endorsed the package.

The deal, which went into effect in January, forced Iran to pull back from the brink of nuclear weapons capacity in exchange for an end to many of the U.S. and European sanctions that devastated Iran’s economy. It has been largely respected despite undiminished U.S.-Iranian tensions throughout the Middle East, including their support for rival sides in Syria and Yemen’s civil wars.

Each side has leverage: Iran doesn’t want a new onslaught of U.S.-led economic pressure and America would be alarmed by any Iranian escalation of its nuclear program. But the accord rests on fragile ground, with powerful constituencies in Washington and Tehran vehemently opposed and looking for any excuse to break it apart. In such a climate, it’s unclear what Trump’s demands for a renegotiation might mean.

“The agreement is valid only as long as all parties uphold it,” State Department spokesman Mark Toner acknowledged Wednesday in the agency’s first briefing since Trump’s stunning election victory over Hillary Clinton to become the 45th president.

Last summer, Walid Phares, a Trump adviser on the Middle East, said Trump wouldn’t pull out of an agreement with America’s “institutional signature,” but rather revise elements through one-on-one negotiations with Iran or with a larger grouping of allies.

Daryl Kimball, executive director of the pro-deal Arms Control Association, said that re-litigating the deal would unsettle American allies, with no clear picture of what Trump would be trying to accomplish.

Trump could also send the deal to Congress, whose Republican majority has opposed it.

GOP lawmakers are examining a slew of possible actions. Among the likeliest pieces of legislation is one targeting sectors of Iran’s economy supporting ballistic missile work, including those specifically exempted from sanctions under the nuclear deal. Another goes after Iran’s Revolutionary Guard for its military activity in Syria and support of terrorism.

Iran could use either as an excuse to push past the limits of the nuclear deal, which may partly explain Republican motivations.

Trump has largely avoided talk of killing the agreement, but has said he would police the deal “so tough they don’t have a chance.”

The U.N. nuclear agency has confirmed minor Iranian violations, specifically on its stockpiling of heavy water that can be used in plutonium production. It has faced no punishment. Iran also has repeatedly breached a ballistic missile ban that was extended for eight years under the nuclear deal, prompting some limited sanctions from Washington.

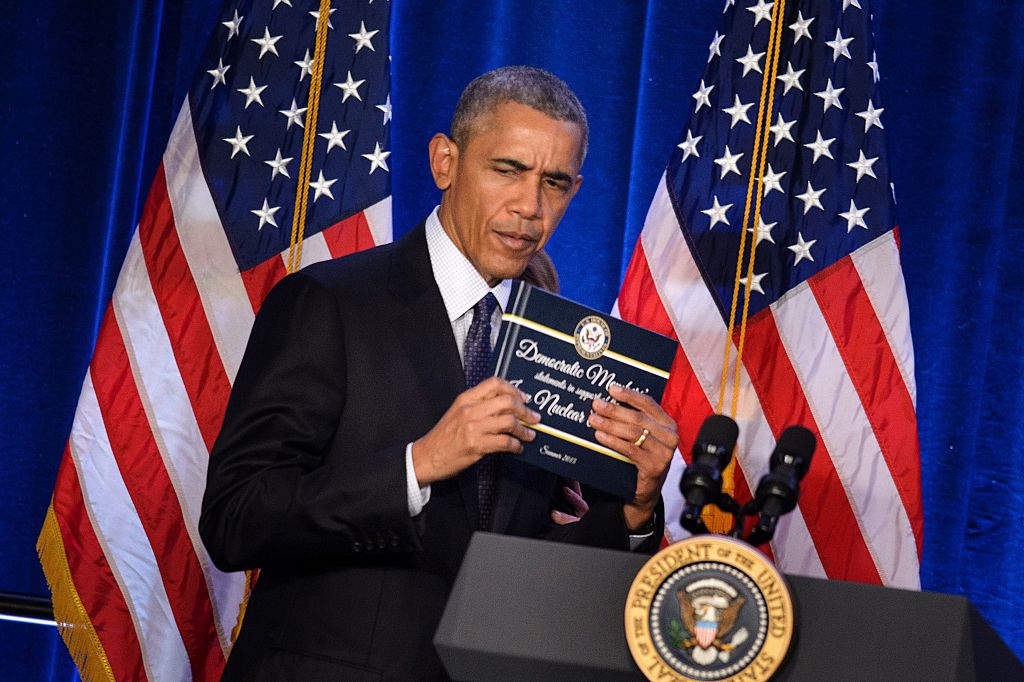

The Obama administration has been hamstrung. Determined to protect the president’s foreign policy legacy, it has gone above and beyond the agreement’s stipulation that no new nuclear-related sanctions be introduced.

When Yemen’s Iran-backed Shiite rebels fired missiles at U.S. Navy vessels, the retaliatory action didn’t extend to Tehran. Nor has Iran faced repercussions for joining Syria and Russia’s offensive in Aleppo, which has drawn U.S. charges of war crimes and crimes against humanity.

And whenever top Iranian officials have complained about the speed and scope of their post-deal economic recovery, top Obama officials like Secretary of State John Kerry have served as pitchmen to international banks and companies hesitant about investing in Iran.

“It is a whole new reality,” said Mark Dubowitz, an Iran sanctions proponent at the hawkish Foundation for Defense of Democracies. What does he expect from Trump? “No more free lunches for the Iranians, no more unilateral concessions, no more excuses.”