America's new immigration policy: Reality vs. words

There is a sense of dread among immigrants in America who fear they will be deported after even minor offenses. The fear among those who entered the country illegally has grown despite the president’s stated priorities.

“We’re getting the bad ones out, okay?” President Trump said in February. “We’re getting the bad -- if you watch these people it’s like, oh, gee, that’s so sad. We’re getting bad people out of this country, people that shouldn’t be -- whether it’s drugs or murder or other things. We’re getting bad ones out.”

But take a look at the executive order Mr. Trump signed in January. It specifies “execution of the immigration laws against all removable aliens” and leaves to “the judgment of immigration officers” whether a person who has not committed a serious crime still poses an unspecified risk, reports CBS News’ Omar Villafranca.

Now in cases across the country the question is: Are we only getting the “bad ones” out?

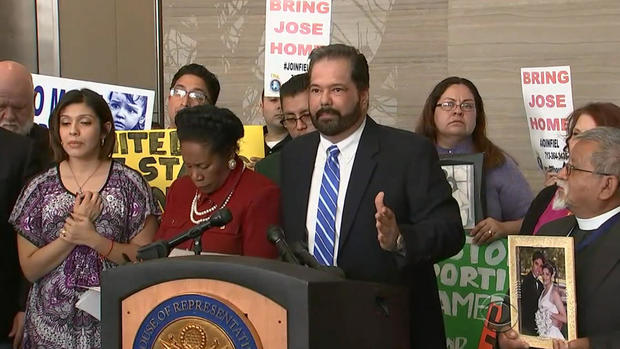

“The only man in my life, you are ripping him apart from me. A part inside me has died,” said Rose Escobar. She is describing what her life has been like since her husband, Jose Escobar, was detained and deported to his native El Salvador two weeks ago.

The father of two has lived in the U.S. for 20 years. He had temporary permission to stay but had missed an immigration hearing and was deported. Escobar’s case is the latest in a series of high-profile deportations.

Romulo Avelica-Gonzalez was detained by immigration officials in southern California while taking his children to school on Tuesday. He’s lived in the U.S. for 20 years. His most serious crime was a DUI conviction nearly 10 years ago. His 13-year-old daughter shot the video of his detention.

In Jackson, Mississippi, this week, 22-year-old Daniela Vargas spoke publicly about her fear of deportation. Shortly afterward, the Argentinian, who came to the U.S. when she was 7, was pulled over, detained and is now in the process of being deported for overstaying her visa.

The arrests follow Mr. Trump’s promise to step up enforcement and deport serious criminals.

“Immigration officers are finding the gang members, the drug dealers and the criminal aliens and throwing them the hell out of our country,” Mr. Trump said at CPAC.

But Raed Gonzalez, Jose Escobar’s attorney, says his client is “not one of the bad guys,” and has never been convicted of a serious or violent crime.

“This individual is not part of what President Trump and his policies have been of deporting criminals,” Gonzalez says. “’Getting the bad hombres.’ Sadly we are getting good hombres deported too.”

Rose, who is a U.S. citizen, vows to fight to get her husband back.

“Why would you hurt me this way? Why would you hurt my kids this way? He’s not a rapist. He’s a godly man. He’s a daddy, he’s a husband. And a son,” Rose says.

In a statement to CBS News, immigration officials say they are focusing on people who pose a threat to public safety, but they also say they are no longer providing exemptions and anyone violating immigration laws may be deported.

In related news, at any given time about 41,000 immigrants are being detained at a cost to taxpayers of more than $2 billion a year. The government says most detainees pose a risk, but at one detention center in Pennsylvania, advocates say many are held without a clear reason, CBS News’ Anna Werner reports.

Dozens of women stood with their children at the fence line of this Berks County, Pennsylvania, detention center in August, to protest. They came from Central America seeking asylum, but were held here for months, their lawyers say, without explanation.

Mothers like a woman from Honduras who asked to be identified as Isabel, were sent to Berks with her 6-year-old son. They were held there for 8 months. A guard was later convicted of sexually assaulting her.

“I felt so alone, I wanted to kill myself,” she said.

Dr. Andres Pumariega is on a government committee charged with investigating immigration detention policies. Pumariega said he doesn’t know why these people have been held for so long, despite being on the advisory committee that was asked to look at all this.

He says they do not present a risk. And most asylum seekers without criminal records are held less than three weeks before being released, sometimes with ankle monitors, and told to come back to court for a hearing.

Many of these families were held for up to a year, yet he says when the committee asked ICE to provide copies of its detention policies, the agency refused.

Pumariega calls it “concerning” and “you wonder if there are criteria ... if there are policies that are clear? Or not?”

His group ultimately told ICE it should “simply avoid detaining families” in part because of the effect on children at berks.

Pumariega said he would describe their mental state as “shell-shocked.”

“These are traumatized kids being protected by and comforted by traumatized moms,” Pumariega said. “And these folks, they think they come for safety and they end up detained.”

We asked ICE why the women and children at Berks have been held so much longer than others but were told by the agency only that “many factors can contribute to the length of a resident’s stay” including the status of their immigration cases. Berks itself lost its state licensing a year and an administrative decision is pending.