Newfound human ancestor may have lived alongside Lucy

Fossils of a newfound humanlike species that lived alongside the famous Lucy about 3.4 million years ago has been discovered, offering proof our family tree is more diverse than some anthropologists believed.

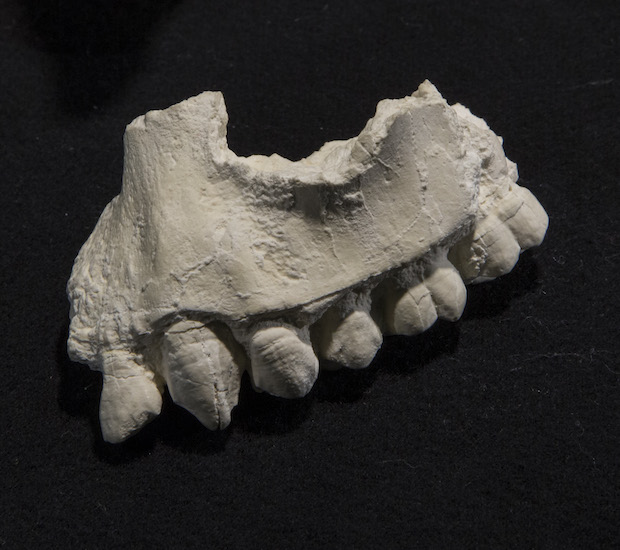

Named Australopithecus deyiremeda, this hominin species lived from 3.3 million to 3.5 million years ago. It was identified from upper and lower jaw fossils recovered from the Woranso-Mille area of the Afar region of Ethiopia and described in the journal Nature Wednesday.

"There is now incontrovertible evidence to show that multiple hominins existed contemporaneously in eastern Africa during the Middle Pliocene," the authors wrote. "In combination, this suggests that multiple hominin species overlapped temporally and lived in close geographic proximity. What remains intriguing, and requires further investigation, is how these taxa are related to each other and to later hominins, and what environmental and ecological factors triggered such diversity."

Scientists long believed there was only one pre-human species between 3 and 4 million years ago, eventually giving rise to the oldest known of the human lineage, genus homo, 2.8 million years ago.

The best known of these early hominins was Australopithecus, such as Lucy's species in eastern Africa, A. afarensis, a small-brained upright biped, which is often considered a remote human ancestor. She lived from 2.9 million to 3.8 million years ago.

But thinking began to change with the naming of Australopithecus bahrelghazali from Chad in 1996 and Kenyanthropus platyops from Kenya in 2001, both from the same time period as Lucy's species. Then came the discovery announced earlier this year of Little Foot, a 3.4 million-year-old foot which did not belong to a member of Lucy's species but indicated its owner was around at the same time.

"This new species from Ethiopia takes the ongoing debate on early hominin diversity to another level," said lead author and Woranso-Mille project team leader Yohannes Haile-Selassie, curator of physical anthropology at The Cleveland Museum of Natural History who also found the foot. "Some of our colleagues are going to be skeptical about this new species, which is not unusual. However, I think it is time that we look into the earlier phases of our evolution with an open mind and carefully examine the currently available fossil evidence rather than immediately dismissing the fossils that do not fit our long-held hypotheses."

Bernard Wood, the University Professor of Human Origins at George Washington University, said the findings would lend support to those who see human evolution as a "fruit bush" with a range of possible candidates leading to modern humans rather than something that looks more like a ladder.

"This new creature belies the fact that human evolution was simple," he said. "You can't explain it away because it has many more similarities to later hominins than chimpanzees. Basically, these guys have provided really good evidence that the single model doesn't work and we need to think about multiple stems."

University College London's Fred Spoor, writing an article in Nature that accompanied the study, agreed it is time to rethink what we know about our ancestors.

"Indeed, it seems that the hominins that populated Africa in the middle Pliocene may have been just as diverse taxonomically as later stages of human evolution," he wrote.

Spoors said the survival of each hominin probably came down to subtle differences in the jaws and teeth of the different species and possibly their use of stone tools, including recently discovered tools dating back 3.3 million years, the oldest ever used by our human ancestors.

The key to their coexisting, Spoor wrote, probably had something to do with "diverse dietary preferences, foraging strategies, habitat selection and population movements."

"These differences provide an opportunity to investigate whether feeding behavior and diet played a part, by modeling the biomechanics of chewing and assessing the dental wear and stable isotopes present in the fossils, both of which can give an indication of the types of food eaten by the individual," he wrote.

Wood, meanwhile, said it could come down to the fact that A. deyiremeda and A. afarensis were using different landscapes. "Was this new hominin living closer or in the trees? Was it adapted to living in the trees while A. afarensis was a hominin that moved away from this adaption and was trying other strategies?"