How would the Senate health care bill actually affect Medicaid?

Democrats and left-leaning think tanks say Senate Republicans' health care bill would be disastrous for individuals and families on Medicaid, the federal program that provides health coverage to low-income Americans.

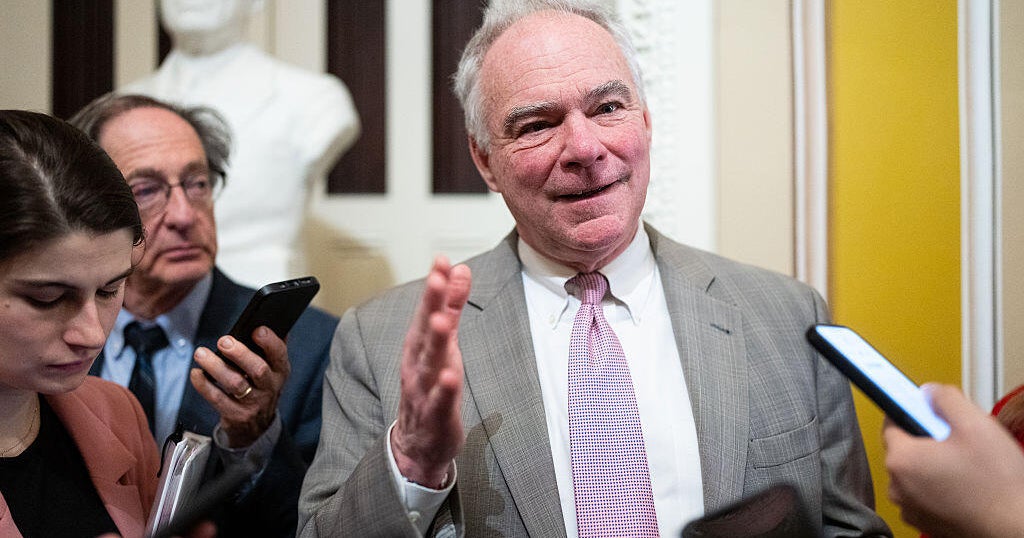

But White House press secretary Sean Spicer on Friday said President Trump is "committed to making sure that no one who currently is in the Medicaid program is affected in any way, which is reflected in the Senate bill, and he's pleased with that."

So, who is right? How would the Senate bill actually affect Medicaid and those who rely on the program for coverage?

The Senate proposal wouldn't cut Medicaid spending in real dollars -- spending would continue to grow -- but it would slow the rate of spending for the program, phase out extra money the federal government has given to states that expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act (also known as Obamacare) and leave states to pick up more of the tab.

Medicaid -- not to be confused with Medicare, the health insurance program for older Americans -- covers roughly 70 million low-income people, pregnant women, disabled people and the elderly. The program is run by the states, which split the costs with the federal government roughly evenly. In 2016, Medicaid spending accounted for $368 billion out of $3.9 trillion in total federal spending, according to the Congressional Budget Office.

Before Obamacare, the program did not cover able-bodied, childless adults. In the more than 30 states that opted to expand Medicaid under the ACA, eligibility for coverage became based solely on income, expanding eligibility to all Americans earning up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level. The federal poverty line for a family of four in 2017 is $24,600, according to the Department of Health and Human Services, meaning families earning up to $33,948 qualify for coverage in the states that expanded Medicaid.

Under Obamacare, the federal government pledged to cover 100 percent of the costs for new enrollees in Medicaid expansion states until 2019, and 90 percent of costs after that.

The Republican bill in the Senate would completely phase out additional federal subsidies for those enrollees by 2024, reverting to the regular, federal-state matching rate applied to the traditional Medicaid population.

But some states expanded Medicaid on the condition that they would rescind coverage for recent enrollees if the federal government decreased funding for the new population. This means that able-bodied, childless adults in Arkansas, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, New Hampshire, New Mexico and Washington could lose coverage much earlier under the Senate bill.

A reduction in federal funding for newly qualified Medicaid recipients would leave expansion states with a difficult decision: drop new enrollees entirely, or pay a much larger share of the bill for their coverage.

But the Senate bill, like the version of the legislation passed by the House in May, also fundamentally transforms the structure of Medicaid spending going forward. Currently, there is no cap on Medicaid spending -- states are guaranteed at least $1 in federal funding for every $1 they spend, and increases in federal funding are considered mandatory spending, rising automatically.

The Senate proposal would cap annual increases on per-person Medicaid spending using the consumer price index for health care, or "m-CPI," as a metric until 2025. Then, the annual per-person spending increases would be tied to the general consumer price index ("CPI-U"), which has a lower average rate of increase. The m-CPI is expected to increase about 3.7 percent per year over the next decade, compared to an expected annual increase of 2.4 percent per year for the general inflation rate.

The difference may not seem like much, but the left-of-center Urban Institute estimates the difference between the two CPI rates could mean a $467 billion difference over 10 years.

From a budget perspective, conservative think tanks like the Heritage Foundation say the cap in the Senate bill helps reform one of the federal government's fastest-growing programs.

Instead of the per-person capita, states could also opt to receive Medicaid in block grants, or a set amount of annual spending that would also increase at the CPI-U rate.

States would also be allowed -- not required -- to impose work requirements for Medicaid, although those requirements would not apply to pregnant women, the elderly or the disabled.

The reduced federal funding for the new Medicaid population, and the restructuring of Medicaid funding entirely, will leave states to find a way to foot a larger proportion of the costs, or find ways to decrease coverage for recipients.

The left-leaning Center on Budget and Policy Priorities estimates that, in the long run, the Senate bill would mean even lower federal spending on Medicaid than the bill passed by the House.

Reducing Medicaid reimbursement rates for providers could also limit access to care. Many doctors already refuse to accept new Medicaid patients because the program's reimbursement rates are generally lower than private insurers and Medicare.

In short, Medicaid funding under the Senate bill would still increase, but at a slower rate, and with states carrying a heavier burden. The bill would almost certainly mean reduced or no coverage for able-bodied, childless adults who are new to the program.

The Senate proposal would affect those currently on Medicaid, contradicting what Spicer said, although the full extent of the bill's effects may not be clear for years.