German drug company apologizes for notorious drug thalidomide - 50 years later

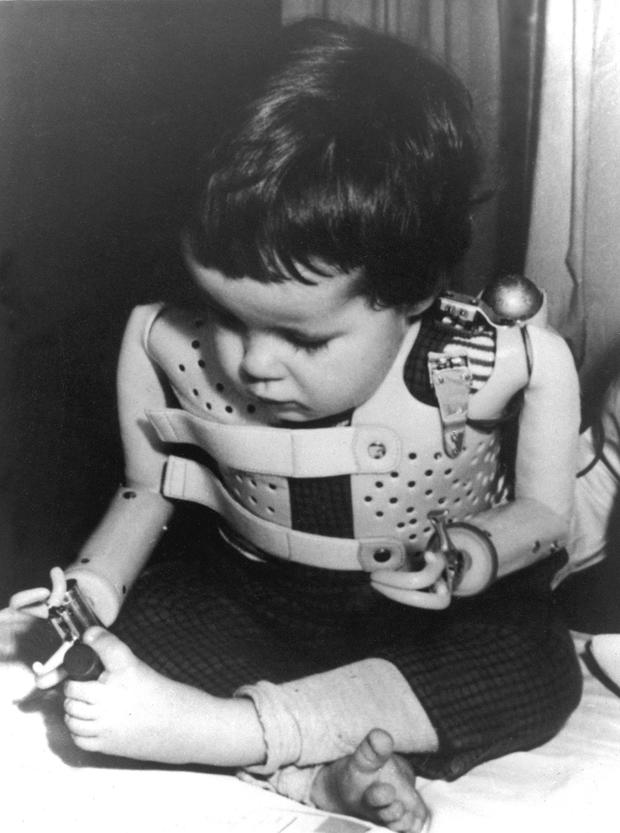

(AP) BERLIN - The German manufacturer of a notorious drug that caused thousands of babies to be born with shortened arms and legs, or no limbs at all, issued its first ever apology Friday - 50 years after pulling the drug off the market.

Gruenenthal Group's chief executive said the company wanted to apologize to mothers who took the drug during the 1950s and 1960s and to their children who suffered congenital birth defects as a result.

"We ask for forgiveness that for nearly 50 years we didn't find a way of reaching out to you from human being to human being," Harald Stock said. "We ask that you regard our long silence as a sign of the shock that your fate caused in us."

Anti-Smoking Drug Banned By FAA

U.S. appeals court strikes down FDA tobacco warning label requirement

Stock spoke in the west German city of Stolberg, where the company is based, during the unveiling of a bronze statue symbolizing a child born without limbs because of thalidomide. The statue is called "the sick child" - a name German victims group object to since all the victims are now adults. In German, the name also implies cure.

The drug is a powerful sedative and was sold under the brand name Contergan in Germany. It was given to pregnant women mostly to combat morning sickness, but led to a wave of birth defects in Europe, Australia, Canada and Japan. Thalidomide was yanked from the market in 1961 and was also found to cause defects in the eyes, ears, heart, genitals and internal organs of developing babies.

Thalidomide was never approved for use in pregnant women in the United States.

Freddie Astbury, of Liverpool, England, was born without arms or legs after his mother took thalidomide. The 52-year-old said the apology was years long overdue.

"It's a disgrace that it's taken them 50 years to apologize," said Astbury, of the Thalidomide U.K. agency, an advocacy group for survivors. "I'm gobsmacked (astounded)," he said. "For years, (Gruenenthal) have insisted they never did anything wrong and refused to talk to us."

Astbury said the drug maker should apologize not just to the people affected, but to their families. He also said the company should offer compensation. "It's time to put their money where their mouth is," he said. "For me to drive costs about 50,000 pounds ($79,000) for a car with all the adaptations," he said. "A lot of us depend on specialist care and that runs into the millions."

Astbury said he and other U.K. survivors have received some money over the years from a trust set up by thalidomide's British distributor but that Gruenenthal has never agreed to settle.

"We invite them to sit around the table with us to see how far their apology will go," he said. "I don't think they've ever realized the impact they've had on peoples' lives."

Gruenenthal settled a lawsuit in Germany in 1972 - 11 years after stopping sales of the drug - and voiced its regret to the victims. But for decades, the company refused to admit liability, saying it had conducted all necessary clinical trial required at the time.

Stock reiterated that position Friday, insisting that "the suffering that occurred with Contergan 50 years ago happened in a world that is completely different from today" and the pharmaceutical industry had learned a valuable lesson from the incident.

"When it developed Contergan Gruenenthal acted on the basis of the available scientific knowledge at the time and met all the industry standards for the testing of new drugs that were known in the 1950s and 1960s," he said.

A German victims group rejected the company's apology as too little, too late.

"The apology as such doesn't help us deal with our everyday life," said Ilonka Stebritz, a spokeswoman for the Association of Contergan Victims. "What we need are other things."

Stebritz said that the 1970 settlement in Germany led to the creation of a 150 million euro fund for some 3,000 German victims, but that with a normal life expectancy of 85 years the money wasn't enough. In many other countries, victims are still waiting for compensation from Gruenenthal or its local distributors.

In July, an Australian woman born without arms and legs after her mother took thalidomide reached a multimillion dollar settlement with the drug's British distributor. Gruenenthal refused to settle. The lawsuit was part of a class action and more than 100 other survivors expect to have their claims heard in the next year.

Thalidomide is still sold today, but as a treatment for multiple myeloma, a bone marrow cancer and leprosy. It is also being studied to see if it might be useful for other conditions including AIDS, arthritis and other cancers.