Georgia special election: a look at the early vote

By Anthony Salvanto and Kabir Khanna

Spanning wealthier and Republican-leaning suburbs north of Atlanta, Georgia’s Sixth District is the kind of place Democrats would love to pull off an upset, not simply for one single district but as a harbinger of larger possibilities. They’d use it to argue there’s greater excitement in their own base – which turnout suggested was lacking last year – and maybe that they can win the sort of upper-income Republicans and college graduates who eluded them in 2016. But it will be a tough task: this is not a district any Democrat historically wins, and Tuesday’s vote requires a candidate to get over 50 percent, or else it goes to a runoff, where the Republican field would not be fractured as it is on today’s ballot.

To get a sense of where things stand, we looked at the early vote – more than 50,000 have been cast so far. While the results haven’t been tallied, we can analyze the vote histories of early voters, based on data collected by L2 VoterMapping and matched to their voter file records.

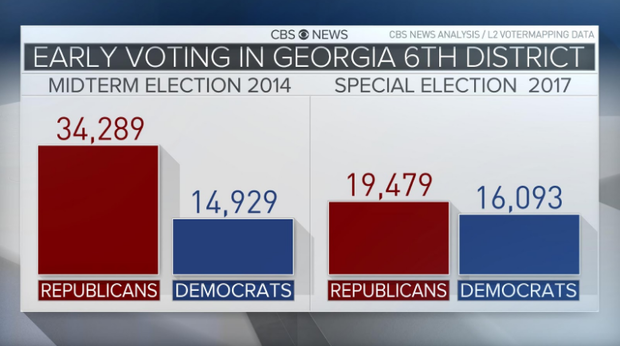

In this special election, the balance between Democrats and Republicans who’ve voted early is closer than it was in the last midterm election, among those who are still on the rolls today. Usually Republicans outnumber Democrats in the early vote, because it is a heavily Republican district.

But this partisan measure comes with a note of caution: figuring out the partisanship of early voters is difficult in a state like Georgia that doesn’t have party registration. We use voters’ past participation in party primaries as a proxy for their partisan preference. While it is not perfect, if you recently voted in one of the party’s primaries, the chances are good you like that party.

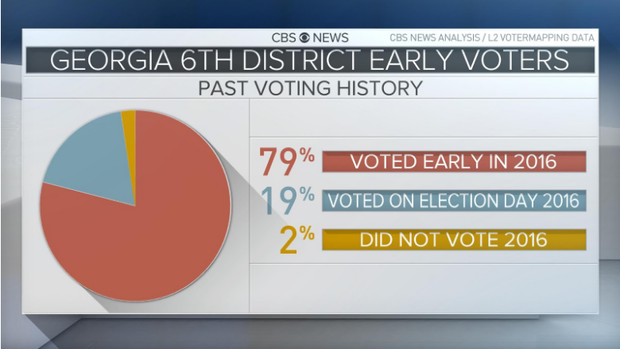

So far, excitement and turnout look like it will have to come mainly from more habitual voters. The early vote data does not show a big uptick in new or lapsed voters who sat out 2016. Almost everyone who has cast a ballot so far in this special election also voted in the most recent presidential election. (And most voted back in the 2014 midterm, too.) So if the Democrats are hoping to bring out people now who didn’t show up last November, there aren’t signs of that yet in the early vote.

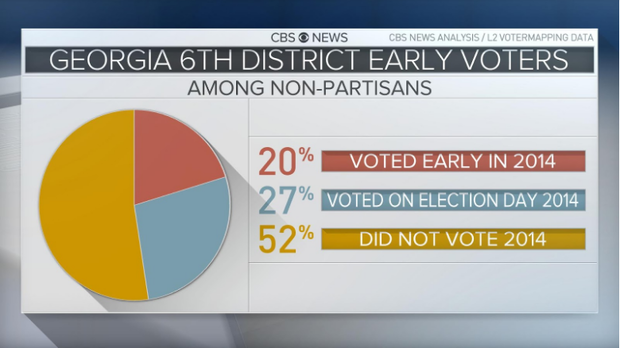

Next we can look at voter history from the last midterm of 2014, which is perhaps a more comparable election to use because, like special elections, they draw lower turnout than general elections. When we look at the non-partisans who have voted early, half of them did not vote in the last midterm. That pattern suggests turnout for this special will at least be higher, should these trends continue, than it often is for special elections. Whether that advantages the either party remains to be seen.

Meanwhile the non-partisans who’ve voted early in the special look demographically more like Democrats, in that one-third of them are minority voters.

More broadly, many of the voters in Georgia’s Sixth are the sort of higher income, college-educated conservatives that were slower to get behind the Trump candidacy in 2016 - though they ultimately did - and so Democrats’ hope is that they might be persuaded to switch come the midterms. (Nationally, at least, polls have consistently shown they’re still supporting the president, though.) Thirty-seven percent of residents in the Georgia Sixth have at least a college degree, 10 points higher than the national district average. The fact that Hillary Clinton appears to have done relatively well here got the attention of both sides.

As the county votes come in Tuesday night, note that the district splits between three counties. DeKalb County is the most Democratic of the three, but it contains a smaller share of registered voters in the district (23 percent) than neighboring Fulton (48 percent) and Cobb (29 percent), both of which are more Republican - and the reason the sixth leans Republican overall. If DeKalb’s vote makes up a disproportionate share of the special election tallies on Tuesday, that would be one sign that the Democrat has a chance to crack 50 percent. Still, many polls have shown him floating in the low to mid-forty percent range.

And note, too, that early vote – however it turns out - is not a predictor of who wins. Democrats have often turned out many of their voters early or absentee only to have Republicans’ election-day turnout more than make up the difference.

And no special election in a congressional district predicts the future, so nothing that happens in Georgia tonight (or a subsequent runoff, for that matter) will in itself tell you who’ll win the House in 2018. These tend to be idiosyncratic affairs. They come around every cycle – some of which draw a lot of attention, but the party that wins may or may not have a good midterm.