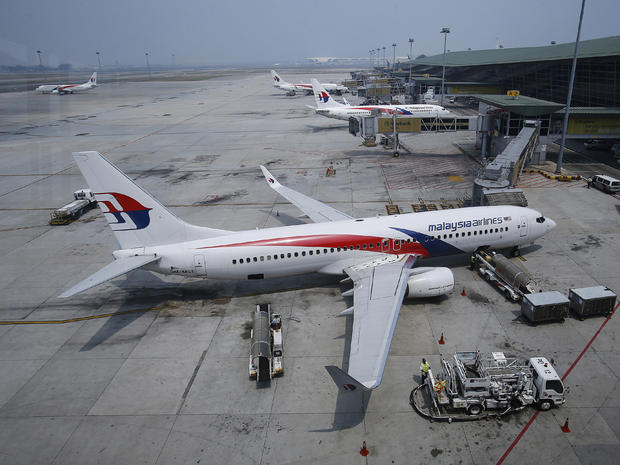

Future of Malaysia Airlines in flux

Shares of Malaysia Airlines, which lost two planes to accidents this year, have tumbled in the wake of the downing of one of its jetliners in Ukraine. On Monday Bloomberg News reported that the government fund that controls the airline is mulling whether to allow the unprofitable company to go bankrupt or take it private.

Malaysia Airlines Flight 17 was en route to Kuala Lumpur from Amsterdam on July 17 when it crashed, killing all 298 on board. Four months earlier, Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 with 239 people on board disappeared over the Indian Ocean. But, as CBS News travel editor Peter Greenberg recently noted, the company has been struggling even before the disappearance of Malaysia Airlines Flight 370, losing $1.3 billion over the past three years.

"The government has been quietly trying to shop them for a bailout for some time," he told CBS Evening News. "There were no takers even before 370. You can imagine the situation right now."

As of the end of March, Malaysia Airlines had about 3.25 billion ringgit on the books, down 13 percent compared with the previous quarter. It may need to sell additional shares to stay in business. The government fund that controls it estimates that it had enough cash to last it for about a year but nonetheless is leaning toward taking it private, according to Bloomberg News.

Even under the most optimistic of scenarios, the road ahead for Malaysia Airlines isn't easy. Consumers in key markets such as China, where many of the Flight 370 passengers were from, have lost faith in the company, and winning them back won't be easy.

"This is not an unsafe airline," Greenberg said. "It's an airline with a great safety record. Although the odds of losing two airplanes in a six-month period are unprecedented."

Among the parties that may be liable for the accident could be the airline, which lost Flight 370 over the Indian Ocean in March, the governments of Malaysia and Holland and possibly, the Russian and Ukrainian governments if evidence emerges proving their culpability, according to the Wall Street Journal. An aviation attorney quoted by the paper estimates the potential liabilities in the "hundreds of millions of dollars."

The Federal Aviation Administration requires all airlines operating in the U.S. to have coverage both for the plane and for liability due to bodily harm or death that may occur to its passengers. Companies who finance airplane purchases by carriers also insist on the coverage. Planes downed by accident or in a military conflict are covered. In fact, about two dozen civilian airlinershave been downed since World War II. The U.S. Navy downed an Iranian civilian jet in 1988 and the government compensated the victim's families.

"A missile strike on an aircraft is fully covered by Malaysia's insurance coverage," said Bradley Meinhardt, who oversees the aviation practice at insurance brokerage firm Arthur J. Gallagher, in an email. "The physical damage is covered under the separate Hull War Risks insurance policy. The liability for passenger deaths is covered under the "extended coverage (war risks)" endorsement to the regular all risks airline liability insurance coverage maintained by Malaysia."

Airlines are liable for about $175,000 in damages per passenger regardless of who was at fault for a particular accident under terms of an international aviation agreement called the Montreal Convention. In order to avoid paying even more money, the airline will have to prove it "took all necessarily measures," said aviation attorney Arthur Alan Wolk, who is based in Philadelphia. That may be a difficult argument for it to make since it was flying over a "war zone," he said.

In terms of victim compensation, "There is going to be a significant delay as there always is in airplane crash cases," said Wolk, who has practiced aviation law for more than 40 years, in an interview. Determining the financial futures of Malaysia Airlines is likely to happen a lot sooner.