For art's sake: When funding the NEA is in jeopardy

The battlelines are drawn in Washington over whether the federal government should be spending any money at all for art’s sake. The impact of the Trump administration’s proposed end to funding would be felt in communities large and small -- perhaps particularly in the small -- as Erin Moriarty reports in our Cover Story:

There is something surprising happening in the Pine Mountains of Kentucky. Like most mining communities, Letcher County has lost thousands of jobs. And yet, how do you account for the new whiskey distillery and restaurant in the county seat of Whitesburg? The renovated buildings? The 15,000-watt radio station?

What has helped breathe new life into the decimated coal economy here has little to do with mining.

“We have 18 full-time employees and five part-time employees,” said program director and fundraiser Ada Smith. “We have over a million-dollar payroll annually.”

This is Appalshop (short for Appalachian Community Film Workshop), a non-profit arts center on the edge of town that exists largely because of federal funding.

“Appalshop has been here in this town for 48 years,” said Smith, “and I think it has been an example of the diversified economy we really need in this region.”

Smith, 29, grew up here. Her grandfather worked in the mines, but because of Appalshop, her father didn’t have to.

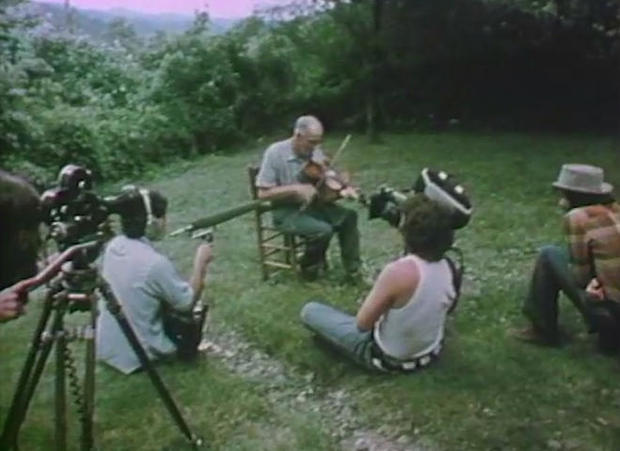

Applashop was a seed that grew out of President Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty in the 1960s. Programs were established in impoverished areas to encourage young people to develop new skills in the arts, like filmmaking. Smith’s mom and dad worked on a Steenbeck in a film editing suite.

The film workshop has grown into a diverse and thriving arts center, where picks and shovels have been replaced by picks and bows. But now, what was started by the 36th President has suddenly been put in doubt by the 45th.

Last month, in what was called the “America First” budget, the Trump administration unveiled a proposed budget that defunds the National Endowment for the Arts, the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Appalachian Regional Commission, and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting -- all of which provide critical funding to Appalshop.

Many of these agencies have been threatened with extinction before. In the 1990s, after Members of Congress accused the NEA of funding offensive art, the agency’s budget was cut nearly in half. But the Trump administration says this time the cuts aren’t about taste, but about taxes and struggling taxpayers.

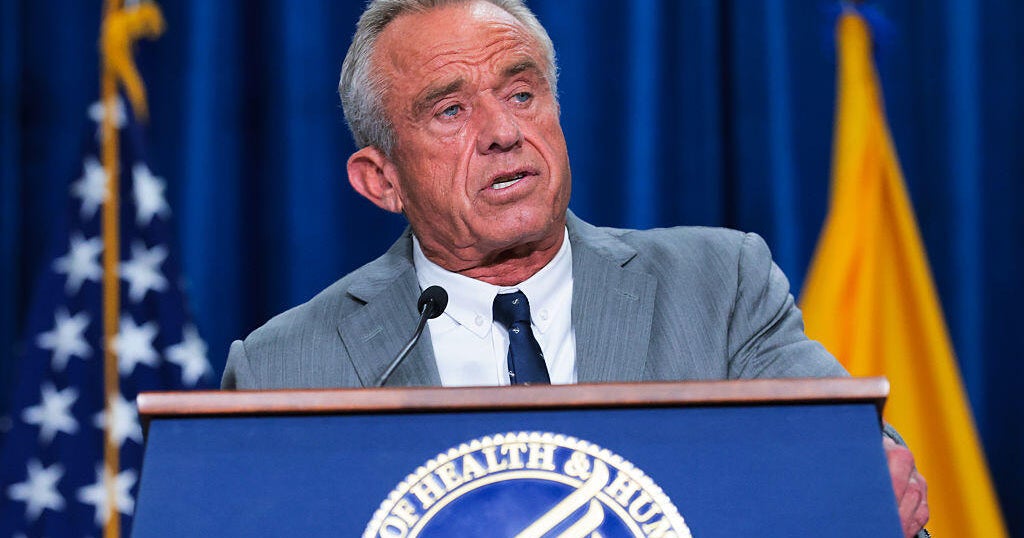

“Can I really go to those folks, look at them in the eye, and say, ‘Look, I want to take money from you and I want to give it to the Corporation for Public Broadcasting?’ That is a really hard sell, and it’s something we don’t think we can defend anymore,” said White House budget director Mick Mulvaney.

This, despite the fact that, altogether, funding for these agencies makes up less than .02 percent of the federal budget.

“To me,” said Smith, “it is, again, really short-sighted and silly.”

Smith says that, in fact, these federal budget cuts will hurt the people struggling the most, in areas that helped elect the President. Letcher County voted 4-to-1 for President Donald Trump.

“The people working on this budget haven’t spent enough time understanding where these types of federal resources go and how much they’re needed in communities like this,” Smith told Moriarty.

With grants from the NEA, Appalshop filmmakers have turned the local culture into indelible images. For example, Appalshop’s films helped document the migration of black families from Alabama to coal mining regions in the first half of the 20th century.

Without federal funding, will this important part of American history and heritage be lost?

Not necessarily, says David Marcus, the artistic director for a theater company in Brooklyn, N.Y. Surprisingly, he support the cuts.

“For 20,000 years human beings have been making art,” he said. “That streak is not going to end in 2018 if the NEA goes away.”

Marcus says that even small government grants interfere with the free market, by giving recipients an unfair edge. “So when the federal government comes in and gives $10,000 or $15,000 to one company and not other companies, they are really putting a heavy thumb on the scale,” he said.

Yes, he says, theaters may fail, but others will simply take their place.

Moriarty asked, “But what guarantee do you have in a place like Whitesburg, Kentucky? What guarantee you have anything that will take that place?”

“I don’t have a guarantee,” replied Marcus.

“So it will just go?”

“Things go, yes. I mean, this is the nature of the world. This is the nature of art.”

But Broadway theater producer Rocco Landesman, a former chairman of the NEA, says, “Art needs subsidy to be alive. You cannot just have the marketplace determining what is done.”

He worries that without subsidies, challenging, daring art will never be produced. Case in point: “If you came to me and said, ‘I’ve got this hot idea for a musical about Alexander Hamilton and the founding fathers and it’s gonna be done in rap and hip hop,’ I woudl say, as a commercial producer, my first take would be, Really?”

The reality is, says Lin-Manuel Miranda, “I’m a Puerto Rican guy who writes musicals and that’s not very common. And as an artist, you’re grateful for any opportunity, any crack in the door.”

Miranda created the Broadway musical “Hamilton,” perhaps the greatest theater sensation of the decade. He credits the success of “Hamilton” -- and his first musical, “In the Heights” -- to federally-subsidized theaters that took a chance on him and his ideas.

“At every formative stage, I can point to public funding of the arts as making that possible,” Miranda said. “My first job was as an intern for WNET, that’s the PBS affiliate in New York City. My first musical was workshopped at the O’Neill Musical Theatre Center which is partly funded by the NEA.”

And it wasn’t just the NEA that made the difference:

“I grew up loving musicals,” Miranda told Moriarty. “I had parents who loved musicals. And we never had money to go see Broadway shows. I think I saw three, maybe, before I was an adult. But because of PBS’ ‘Great Performances,’ I saw ‘Into the Woods.’ And it changed my life.”

And that, says Miranda, is the point: to give children who otherwise wouldn’t have it access to the arts, like 11-year-old Jamin Radosevich and his older sisters, Samantha and Grace, in Letcher County, Kentucky. Appalshop is the reason they have been able to take music lessons.

“If you hand me an instrument, I want to learn how to play it,” said Grace. “So I was excited when I could learn the fiddle.”

The costs of funding these programs are only a tiny fraction of the federal budget. But NOT funding them, Ada Smith says, would cost Americans much more.

“We try to tell the stories of the people and amplify their voices, their lives, their stories,” Smith said. “When you take away that type of federal support, you start weeding out tons, millions of voices in this country, that are unheard.”

For more info:

- National Endowment for the Arts

- Recent Grant Search (NEA)

- Appalshop

- Lin-Manuel Miranda (Official site)

- Urban Arts Partnership

- New York Youth Symphony

- Bluebox Theatre Company, Brooklyn, N.Y.