On crime-ridden streets, a priest and his school offer a way out

NEWBURGH, N.Y.-- At first glance, the phrase painted boldly above the building's entrance seems an unlikely motto for a school - "The street stops here." But it fits well for those who know what life is like for students at San Miguel Academy in Newburgh, New York, according to the school's president

"Newburgh has the greatest need in our region," said the Rev. Mark Connell, who is also one of the all-boys school's co-founders. "It is one of the poorest urban centers in the United States. It is one of the most violent cities in America ... so there is a compelling reason here in Newburgh to offer an alternative to kids who have to grow up in an environment such as this. To give them an opportunity, and educational option, to open new horizons."

Newburgh is located on the west bank of the Hudson River, about 60 miles north of New York City and about 12 miles from the United States Military Academy at West Point.

The city has had a history of gang activity and violent crime. With a population of more than 28,000, city of Newburgh has the highest violent crime rate per capita in New York State. New York Magazine dubbed it the "Murder Capital of New York."

The Newburgh City Police Department and the FBI - the bureau has a task force located in Orange County - started working together in 2007 as gang violence soared. During this time, "a lot of the homicides were related to these gangs" said acting Police Chief Daniel Cameron.

While the police and FBI have cited progress dismantling several organized gangs, such as the Bloods and the Latin Kings, gang activity still poses a risk to the city's youth.

Connell believes the best way to prevent kids from being lured into the gangs is through schooling that literally keeps them off the streets, at least as much as possible.

Classes at San Miguel are held six days a week for 11 months out of the year. While the school day extends over a typical 8:30 a.m.-3 p.m. schedule, there are after-school activities that can keep students occupied until 5:30 p.m.

The small faith-based middle school - serving grades 5 through 8 - has 64 students, comprised predominantly of Hispanic and African-American kids, in line with the city's demographics.

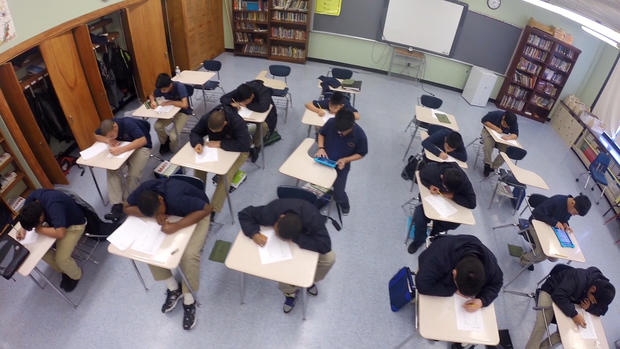

Classes are small, with an average of 16 students at each grade level. Aside from learning traditional subjects, students also gather in the middle of the day for 20 minutes of calisthenics -synchronized jumping jacks and pushups - before lunch. Weaved throughout the day are also chores the boys help with around the school. Although classes end at 3 p.m. that doesn't mean the day is done. The boys have an hour of homework time and then participate in after-school clubs and activities like rowing and basketball.

Keeping these kids off the streets for as long as possible is critical because they're at an age where they're particularly vulnerable to gang recruitment, said Connell.

When it comes to recruitment, it's the "younger the better" for these gangs, said Cameron, the police chief. "Usually gangs are associated with a 'family.' So if a young kid doesn't have guidance from their family then they become a member of these organizations - and it becomes their family. And they have to established themselves in the group and usually that's by committing crimes."

Connell's solution is offering a positive alternative to the negative ones that exist on the street.

The 55-year-old Catholic priest has been a teacher in New York for 30 years and came to the Newburgh area in 1998, serving at the time as a college professor and chaplain at Mount Saint Mary College. It was during this time when he began to see the depth of poverty and crime that surrounded him. Drug deals, gunshots and body bags were never too far removed from one of his former homes in the city, he said.

"It was right at my doorstep. And I felt compelled to do something about it. I saw children who should be in school, not in school. And I realized that one way out of poverty, probably the only way out of poverty is education, and hard work."

So in 2006, Connell helped establish San Miguel to offer low-cost education to boys at risk of sliding into the spiral of violence and crime he had seen around him. It's not a big operation, featuring just five full-time teachers and relying on supplemental help from volunteers, district-supplied special education teachers, and privately hired social workers. But what it lacks in size, it makes up for in affordability - families are required to pay just a $40 (or sometimes less depending on need) activity fee every year. That's because the school relies almost solely on donations from individuals, corporations, trusts and foundations. While faith-based, the school isn't affiliated with the Archdiocese of New York and receives no financial support from it.

While education is the priority, the school offers another vital component in students' lives - stability and security.

"Some boys have to call home ... they want to hear a voice, they want to make sure mom is okay," said Connell. "It's incredibly stressful on one's psyche to know that at any particular time of the day something could go wrong that could harm you, hurt you, or even worse, kill you."

Anthony Cruz, who is currently seventh grader at San Miguel, said that living in constant fear is tiring. "There's going to be a day where one of my family members' going to get really hurt," said the 12-year-old, tearing up as he spoke.

Jesus Cruz, Anthony's oldest brother, is one of San Miguel's success stories. Now 19, Jesus just completed his first semester at Fairfield University. But when he first arrived at San Miguel, as a 6th grader in 2007, the idea of attending college seemed remote.

"Growing up most of my friends and relatives they were influenced in gangs. That's what I grew up with, knowing about gangs, drugs, skipping school, skipping class, that's all I knew," said Jesus.

Connell said it was a slow process to get Jesus headed in the right direction.

"If you were to look at his report card when he entered here, it was nothing really to get excited about. But we recognized while he was here, there's a bright kid ... who's capable of being on a college track, and we said we want to get him there. And he didn't believe that in himself," said Connell.

Jesus credits Connell and the staff at San Miguel for their encouragement to do better in school in order to get into college. The faculty instilled that college was the goal, and that, Jesus said, is what really drove him.

"They've given me hope. Before San Miguel I didn't believe in myself," said Jesus. "They gave me that view that if I just focus and give it my hardest that anything is possible."

San Miguel's support in academic achievement goes beyond its own doors. Not only does the school offer guidance in selecting a proper high school for each boy, often one located outside of Newburgh, it also offers financial assistance - typically in the range of $1,000 to $5,000 a year - if needed through both high school and college.

Because most boys are the first in their families to go down this educational path, they keep track of the students' progress beyond 8th grade, pushing them to "achieve to their full potential," said Connell.

Jesus, who is the first of his family to go to college, was taken aback by the level of support after leaving San Miguel to attend St. Benedict's Preparatory School in Newark, N.J.

"That was a shock for me ... because after leaving San Miguel I really didn't think I was going to hear about them no more. I was wrong, as soon as I started going to St. Benedict's they started to get every feedback," said Jesus.

Currently there are 67 students in the high school and college support program. Connell said all of their boys so far have graduated from San Miguel and high school. Of the 12 boys in Jesus' graduating class at San Miguel, 10 are now in college.

That success, though the sample size is small and the data self-reported, compares favorably with the Newburgh enlarged city school district, which reported a 69 percent graduation rate in 2012-2013. Among those considered economically disadvantaged, the graduation rate was 60 percent.

All of Jesus' siblings aspire to follow in his footsteps and go to college. Jesus said a large part of that wouldn't have been possible without Connell.

"Father Mark, I think he was like a guardian angel sent from God. If it wasn't for that man, I don't know where I would be right now," said Jesus.

But Connell is quick to credit everyone that works at San Miguel for the success of the students.

"Anybody who spends any time at San Miguel realizes that there's a village behind every kid. We have the most incredibly talented and dedicated staff, they do the hard work, they're in the trenches everyday. In fact there is a lot of angels here, and they all get behind these kids," said Connell.