Families of Korean War's missing soldiers still bear scars

When Robert Morin saw his father's name on the memorial wall, he laid his hand on its engraved surface and began to sob. Morin was only 6-years-old when his father, Marine Corps Captain Arthur Morin, went missing in action during the Korean War.

Captain Morin was flying an observation aircraft near the demilitarized zone between North and South Korea on October 4, 1952 when his plane was struck down by anti-aircraft fire. Witnesses said he was pulled from the plane by North Korean soldiers and executed.

Captain Morin's body was never found, but his name is etched alongside other missing American sailors, soldiers, airmen and Marines on the walls leading into the War Memorial Museum of Korea. It was a gesture of gratitude his son hadn't expected.

"I've never seen him memorialized or commemorated or anything of that nature in the United States and to come all the way to Korea and see his name on the wall was a shock, a surprise and something I was not emotionally prepared for at the time," Morin said.

In May, Morin and the siblings, spouses and children of two dozen U.S. service members still missing from the Korean War were invited as guests of the South Korean government to visit the country where their loved ones were last seen alive.

Most of the family members who made the trip, like John Zimmerlee, grew up not with their fathers, but with the posthumous Purple Hearts they left behind.

"They called us war orphans," John Zimmerlee explained. His father, U.S. Air Force Captain John Henry Zimmerlee Jr., was the bombardier of a B-26B Invader bomber. During a night mission on March 22, 1952, contact was lost with his aircraft.

"He wasn't known to have been killed in action. He wasn't known to have died in a prison camp. He was just missing."

"MIA is a very difficult term to live with, not knowing," Sharon Durrell agreed. She still has the telegram from 1950 informing the family that her father, Air Force Captain Claude Batty Jr., was missing following a night intruder mission near Seoul. "He's buried in Arlington. Just a memorial, there's no body there because they never found him."

Marion Harrison understands what it's like not to know. The fate of her first husband, Army Corporal Lyman Lewis, has been as elusive as the knowledge of whether he lived long enough to find out that she'd given birth to their first and only son. Corporal Lewis was taken prisoner near Kunu-ri, North Korea in December of 1950.

Their son is now 65, but Harrison still vividly remembers the day she learned her husband was missing.

"My mother was at the house with me and I told my mother, 'Something is wrong because I haven't heard from Lyman,'" Harrison reminisced to CBS News. "I bet you it wasn't an hour later the man knocked on the door with the telegram that said he was missing in action."

In past years, South Korea's Ministry of Patriots and Veterans Affairs has offered paid Korea trips to veterans of the Korean War, but this was the first time the government extended the invitation to the families of missing men.

Nearly 8,000 U.S. service members never came home from Korean battlefields, including Timothy Ganahl's brother, Army Second Lieutenant William Otis, Jr., a graduate of West Point Academy.

"He was a member of the class of 1950, almost all of whom got sent over here within 90 days of their graduation," Ganahl remembered. "They'd never had any combat experience, not even just the normal first year of going to a U.S. base and operating before they would ever be put into combat."

That year's graduating class earned the tragic distinction of having the highest casualty rate in the history of West Point at the time. Second Lt. Otis Jr., was one of those casualties. He's believed to have died less than a month after arriving in Korea and just days after being awarded the Silver Star.

Decades later, the tone of his brother's trip was set early, when a small army of South Korean guides met families at the airport offering not only assistance, but also indebtedness for the sacrifices their American guests made more than half a century ago.

"The authenticity of their gratitude is astonishing," Morin gushed, surprised. "I mean they could not possibly fake what we're experiencing from people here. There aren't that many good actors in South Korea to pull that off."

The families were escorted as VIP guests through museums, a palace and a Korean folk village. They were treated to the riotous color and pageantry of a country drumming ceremony, the graceful and elegant beauty of the buchaechum (a traditional fan dance with roots in shamanic ritual) and an achingly ethereal concert sung by the elite children's performing arts group, the Little Angels.

But unlike any other guided tour of the country, the South Korean government dedicated the majority of this trip to honoring those they say will always be their heroes.

Memorials were held for lost loved ones at the Korean War Museum, the National Cemetery and at Imjingak - near the ironically named and heavily patrolled demilitarized zone separating North and South Korea - where Korean soldiers in full dress uniform carried pictures of each family's lost loved one. It was a tender expression of honor that transformed the way self-proclaimed war orphans like Zimmerlee viewed their personal loss.

"All of a sudden, I'm here with all these other war orphans and all those pictures kind of arose in one line behind me it was like all the guys were here, the guys that were missing, they had come back to their families," Zimmerlee said, fighting back tears. "It just hit me, I turned around and saw the sea of pictures and all of a sudden, it made sense."

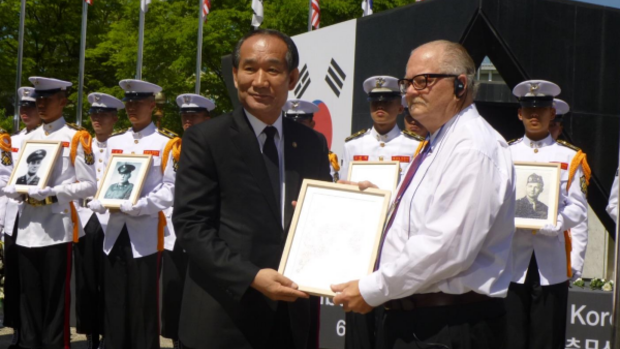

At a banquet that same night, the Minister of Patriots and Veterans Affairs Park Sung-Choon personally presented each family with a medal in acknowledgement of the price they paid for South Korean independence. For some, it was more recognition than they expected.

"It means a lot to know that somebody cares," Harrison said.

"It's been off the charts," James Elliott said of the trip. His father, Army 1st Lt. James Homer Elliott, disappeared in 1950 after volunteering for a night patrol along the Naktong River. "The Korean people are just phenomenal, their gratitude is something that I just can't fathom."

For Elliott and his sister, Jorja Reyburn, it was also an opportunity to bring their parents closer together. They carried the cremated remains of their mother, who died in February, to Korea to scatter near the river where their father went on his final patrol.

"It's been extremely emotional," Elliott said. "I've never experienced anything like it in my life."

Heartrending -- an apt description provided by retired Army LTC John Phillips and his sister Carolyn Phillips of the experience. Their father, Army Major John Jason Phillips, disappeared in November of 1950, leaving behind a wife and three children.

"We lost our mother several years ago," Phillips said. "She died when she was about 97-years-old. She lived a long fruitful life, but a lonely one without her husband."

Loneliness has been a common thread woven into the lives of these forgotten families of a forgotten war, haunted by hope and desperate for answers they have to convince themselves may someday come. But though the ultimate fates and final resting places of their loved ones might always lay just out reach, a sense of closure may not.

"He wanted me here," Gail Embery believes of the dad she never met. As a result of her mother's grief, she was 10-years-old before she learned the man in the picture on the wall she'd been admiring for years was really her father, Army Sgt. Coleman Edwards. "I definitely feel that he guided me to this place. And I definitely feel that he's with me."

Missing Men And The Miracle On The Han River

On the morning of July 27, 1953, inside a hastily erected pagoda on a dusty road in central Korea, the fate of two nations was decided. Ceasefire replaced an unobtainable peace and Korea, for the second time since World War II, was split in half, pawns in a geographic and ideological tug-of-war. Communists on one side. The United Nations on the other.

After years of fighting and failed peace negotiations, both were in bad shape.

The Land of the Morning Calm lay in ruins. People were starving. Millions had died. More than a hundred thousand just disappeared, including nearly 8,000 U.S. service members still listed as Missing in Action today.

"I grew up thinking I was just cheated of a father for what?" Lou Ann Edwards asked no one in particular. For more than sixty years, no one had been able give her the answer she needed.

Her father, U.S. Air Force Capt. Louis Holland, the pilot of a B-26B Invader bomber, went on a night mission in Korea on June 13, 1951 and never came back.

"I mean, I didn't even know where to look on an atlas to find where Korea was," Edwards recalls. "I had no idea. I mean what would be so important that he would die for? For all these years, I would have had a father for all these years."

Suzanne Schilling and Mary Loftus also grew up without their father. Marine Major George Major's fighter plane, an F9F-2B Pantherjet fighter, was shot down by anti-aircraft fire on Jan. 3, 1952.

"What I knew about Korea," Schilling said, "was that there was a war and my father disappeared."

At the time the war began, Korea likely knew little more about itself. Prior to World War II, the entire Korean peninsula had been ruled by Japan - one nation in the shadow of the Rising Sun.

When the Japanese surrendered at the end of WWII, their victors claimed the spoils and Korea was split down the middle along a latitudinal line. Russia took everything above the 38th parallel, the United Nations became responsible for everything below.

An uneasy truce that lasted only a handful of years, until June 25, 1950 when 75,000 North Korean troops marched down a dirt road and invaded their southern neighbors. Five days later, U.S. President Harry Truman ordered American ground troops into action.

The Korean War had begun.

Within months of being put in combat Army Pfc. 1st Class Ivey Barnett was taken prisoner by the North Koreans near Unsan. He's believed to have died in prison Camp 5 on March 31, 1951.

"After he died I was extremely bitter," Barnett's sister, Betty Mae Bradshaw, admitted. "He shouldn't have gone to begin with because he was just really a kid. He was only 17 when he left and only 18 when they declared him dead. And I thought this really just wasn't worth it for him to have given up everything for."

More lives were lost as the battles raged. Territory was gained, lost and regained. Seoul, the capital of South Korea, changed hands four times during the war. Many of its inhabitants became refugees in their own country. In three years, the city went from having 1.4 million residents to just 133,000. Those who remained lived in the rubble of their twice-conquered city.

Then, three years after the war began an armistice was signed in Panmunjom, 35 miles north of Seoul, on the only road that existed uniting the two countries. Technically, the war never ended, it just paused. On the same dirt road where it began.

"As I saw it from where I was, with all the people that were killed in the terrible war that went on, and then for them to end up at the same line it felt like, what was that for?" Prudence Moore has wondered for much of her adult life.

As a child, Moore had a recurring dream that her father, Marine Col. Arthur Chidester, would find her as she was getting on her school bus one morning and give her a big hug. She wasn't even 2 years old when Chidester was taken prisoner in North Korea. Moore's sister, Mary Borevitz was 7 years old.

"A person spends time with what they love," Borevitz reasoned, "so obviously he didn't love us if he thought fighting and going away was more important than our family. It was very hard for me."

Colonel Chidester was declared "presumed dead" on Jan. 14, 1954, at a time when South Korea was struggling to rise from the ashes.

"This country has no future," Gen. Douglas MacArthur, former Supreme Commander of Allied Forces in the Southwest Pacific Area, said of Korea during its war. "This country will not be restored even after a hundred years."

He had good reason to believe that. Throughout the Korean peninsula, the war destroyed 80 percent of power plants, nearly half of all railroads, roads and bridges and roughly one in five homes. Homeless and laboring in darkness, the average South Korea family earned just $64 a year. But the people were free.

"I grew up with all the stories, my mom and dad told me what the United States did," Sunny Lee, who grew up in South Korea, told CBS News. "America was the huge impact to win this war and so just words are not enough to express American soldiers' sacrifice and their dedication."

Lee, a full-time volunteer now living in Utah, wanted the families of U.S. servicemen still missing from the Korean War to have a chance to visit her homeland and feel the gratitude of its people. She petitioned the South Korean Minister of Patriots and Veterans Affairs to host a trip and, in May, she accompanied nearly two dozen siblings, spouses and children of missing men to Seoul.

But the South Korea in which the families arrived bore little resemblance to the wasteland described in decades-old letters written by their lost loved ones.

In just over 60 years, South Korea had used the billions of dollars it received in foreign aid after the war to transform itself into the world's 11th largest economy. It is now also the world's 7th largest exporter, partly due to the success of popular Korean brands like Samsung, Kia, LG and Hyundai.

South Korea has also earned the distinction of being the first country to go from being the recipient of international development aid to being a donor, earning a place on the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development's prestigious Development Assistance Committee (DAC).

Economists refer to South Korea's explosive growth as the "Miracle on the Han River" -- a miracle that South Koreans insist resulted from the American and UN sacrifices that earned them their freedom.

Mary Borevitz hadn't expected such gratitude for something her father did so long ago.

"He was doing something that in the larger picture of the world was very important and made a huge difference in millions of people's lives. And that's put a different picture on my own sorrow and difficulties I've had in my life because of not having a father," Borevitz said.

A sentiment echoed by Suzanne Schilling. "Coming here has made a big difference. Understanding that they really appreciate what our fathers and our brothers did by coming over here and helping them fight for their independence."

For the first time, family members were able to see the war that never officially ended as a win for America.

Robert Fenton's father, 1st Lt. Robert Rood, was reported missing in action in 1953 after fighting one of the last battles of the war.

"This has given me a whole new dimension to my father's experience and a wonderful introduction to this land and it's people," Fenton said at the conclusion of the trip.

That change in perception, transforming sorrow into pride, was exactly what Sunny Lee had hoped for when planning the trip.

"I'm very happy to do this to pay back for their sacrifices," Lee said. "The reason I am doing this is because of them, Korea exists and I am here too. So I owe them my life and this is part of my payback to them."