Elder scare: Low pay afflicts America's fastest-growing job

The fastest-growing occupation in the U.S. is also among the lowest paid.

The aging of America's baby boomers has led to a surge in demand for home care workers to look after the nation's elderly, as well as the disabled and chronically ill. The work is as essential as it is poorly paid. Home health aides do everything from checking a client's vital signs and administering medications to looking after people's dietary needs and even operating life-sustaining equipment, such as ventilators.

"We're talking about the people caring for the most important relationships you have," said Ai-Jen Poo, director of the National Domestic Workers Alliance and author of 'The Age of Dignity: Preparing for the Elder Boom in a Changing America.' "When you have a situation where the people we count on to take care of our families can't take care of their own, there is something fundamentally wrong."

Working poor

Despite the growing need for home health services, in 2012 (the latest year for which data is available) the median annual wage for the country's nearly 2 million so-called direct care workers was about $10 an hour, or less than $21,000 per year, according to the U.S. Department of Labor. The money can be even worse, industry data show, since many people in the field are paid a part-timer's hours despite putting in a full work week.

Among the factors combining to keep a lid on pay, experts say: a large pool of low-skilled workers, most of whom are minority women; weak union representation; and federal laws that exclude home health personnel from the wage protections common in other professions.

"Perhaps the largest reason for aides' low wages is because care work, which makes up the majority of home health care aides' duties, has been traditionally undervalued in our society," said Robert Hiltonsmith, a policy analyst with Demos, a left-leaning think tank, in a 2014 report.

The poverty line is $24,250 per year for a family of four and $11,770 for an individual, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

Another oddity, given the growing demand for home health workers: Over a 10-year period, their hourly pay has seemingly defied the laws of supply and demand and fallen roughly 50 cents, according to the Paraprofessional Healthcare Institute, which represents direct-care employees.

The low pay leaves many home health workers struggling to make ends meet, with only fast-food workers earning less. And like those employed in the restaurant and retail sectors, where financial insecurity is the norm, home care workers often face unpredictable schedules that can wreak havoc with family life or other priorities.

"I feel my job is a real job and it should be treated like a real job. Treat me with the respect it deserves," said Roxanne Trigg, a home care provider in Milwaukee. "It's hard to the point where sometimes I have to make a decision which bill I can pay this month, or something gets cut off or cut out."

For home health firms, meanwhile, the measly wages result in turnover ranging from 50 percent to 70 percent annually, according to PHI. It also makes recruiting and retaining workers difficult, affecting quality of care.

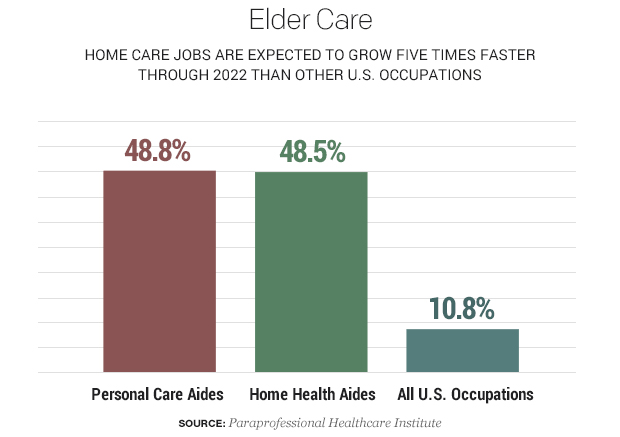

Demand for home care is only expected to escalate, and sharply, as boomers get older -- about 10,000 Americans turn 65 each day. This is increasing the national appetite for home care, a less costly and often preferable alternative to nursing homes and hospitals. As Americans age, the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics projects a 48 percent hike in employment of home health aides from 2012 to 2022, far faster than the average for all jobs.

"Home care is expected to add more jobs than any other occupation or industry in the next 10 years," said Abby Marquand, director of policy research at PHI. "It's really booming. Even when our economy was in decline, the demand didn't go away. It's a recession-proof industry."

Proponents of the rapidly expanding home health industry argue that boosting wages would raise their labor costs, resulting in price hikes to the elderly and disabled, often financially disadvantaged themselves.

"We understand the conversation about compensation, and obviously there are two sides to the story, but we want to make sure folks know that raising the costs will put [home care services] out of the financial reach" of many users, said Robert Cresanti, executive vice president of government relations at the International Franchise Association.

Critical court fight

The IFA is one of three groups challenging revised rules from the Labor Department that had been slated to take effect at the start of 2015 that would have meant third-party providers of home care services were no longer exempt from paying employees minimum wage and overtime.

"The industry was sweating and struggling to deal with the change to regulations throughout 2014. It's a real challenge from an employers' perspective," said Peter Godfrey, a lawyer at Hodgson Russ who represents home care providers across New York.

Opponents of the exemption say removing it would lift the living standard of nearly 2 million home-care workers, and make it easier to recruit and retain workers in a profession with a high turnover rate.

But industry advocates say the Labor Department's new rules would have increased costs for those using the services.

"One of our hallmarks is to provide a service that is safe and affordable in a quality manner," said Phil Bongiorno, executive director at the Home Care Association of America, or HCAOA, which represents private-duty home care providers. "If it becomes unaffordable, clients will try to find care on the black market, where's there's no regulation."

Maury Baskin, an attorney at Littler Mendelson, which is representing home health agencies in the industry's legal challenge to the DOL rules, adds that raising wages for workers means many consumers "would no longer be able to afford home care and have to resort to institutionalization. That's what this is about, the affordability."

Advocates for direct-care workers -- 90 percent of whom are women, most of them minorities -- say employees deserve a bigger cut of the revenue their labor generates, highlighting the significant spread between billing rates for home health services and workers' wages.

The national hourly cost of services ranged from $18.75 an hour for "companionship" services to $22.37 for full-fledged home health services, according to a member survey conducted by the National Private Duty Association and published in 2009, the last year the group published the figures.

Profit-sharing?

At the same time, starting hourly pay for those providing companionship services -- in which workers provide company and protection to those unable to care for themselves -- came to $8.92 an hour and $11.78 for home health services, a difference of approximately 50 percent.

"The industry 40 years ago looked nothing like it does today. Our system of long-term care has changed dramatically," said Marquand. "In the meantime, the industry has become a $90 billion industry, with home care franchises topping the list as among the best businesses to own. There are profits to be made there, and you can see why if you don't even have to guarantee your workers minimum wages and overtime."

Revenue in the home health industry has increased 48 percent during the past decade, according to a report released this week by the National Employment Law Project (NELP), which used data analysis and modeling from the University of California Berkeley Labor Center in coming up with the estimate.

CEO compensation at the four publicly traded national home health care chains, adjusted for inflation, has risen more than 150 percent since 2004, while average hourly wages for home care workers, also adjusted for inflation, have dropped nearly 6 percent in the same time frame, NELP found.

In two recent rulings, U.S. District Court Judge Richard Leon found in the industry's favor, invalidating the DOL's revised definition of companionship services care and finding third-party providers to be exempt from mandates under the Fair Labor Standards Act that covered workers get paid minimum wage and overtime pay for working more than 40 hours a week.

The DOL had clarified its definition to include only social, physical and mental "fellowship" activities and "protection" services, like being nearby to ensure a client's safety, saying it was updating the rule reflect changes in the industry since the exemptions were first enacted in 1974.

"The Department intends for the exemption to apply to those direct care workers who are performing 'elder sitting' rather than the professional workforce for whom home care is a vocation," the DOL wrote.

The issue of getting paid the minimum wage, which has been $7.25 an hour for nearly six years, is less of an issue for home care workers, whose hourly rate is generally higher than the minimum. More important to home care workers, who often must administer round-the-clock care, is qualifying for OT.

One way to "keep the service affordable was to potentially split up shifts," said Bongiorno, meaning multiple caregivers would have to provide the care previously given by one, a move that could prove particularly disruptive to seniors with Alzheimer's or dementia.

The primary effect of its rule, according to the DOL, would be to transfer an average of $321.8 million a year in income from home care agencies and payers around the U.S. to direct-care workers. Specifically, restricting the companionship service exemption would mean workers would be paid for time traveling between clients receiving their services from the same employer and getting paid a premium for hours in excess of 40 a week.

"We're supportive of the [DOL's] rule, but we've also taken the position that we want to see it implemented in a way that doesn't hurt people with disabilities or seniors," said Joe Caldwell, long-term services and support policy director for the National Council on Aging. "The implementation really needs to happen in a thoughtful way, if it's done wrong, they could say we're not letting anybody work over 40 hours."

That's a debate that had been playing out in some states. In California, the state legislature rejected a move by Gov. Jerry Brown that would have capped hours for home health workers supported by taxpayers, with the Democratic governor saying the state couldn't afford the increased overtime costs. Brown subsequently signed a budget in June that included $180 million for overtime pay for home care workers, but the state then opted not to implement the overtime pay after Leon's rulings.

But such cutbacks could affect those receiving and supplying home care, Marquand warned. "Service recipients are fearful if state Medicaid budgets [are squeezed] that might mean reduced services," she said. "You're basically looking at two populations -- one mostly minorities, 90 percent women, servicing consumers who are also marginalized, disabled, older and often in poverty."

The DOL is appealing Leon's decisions, saying it believes its new rule "is legally sound and is the right policy -- both for those employees, whose demanding work merits these fundamental wage guarantees, and for recipients of services, who deserve a stable and professional workforce allowing them to remain in their homes and communities."

The U.S. Court of Appeals in the District of Columbia called for briefings in the case to be completed in early April.

"We're confident that the regulation will eventually go through, that this is just a delay of implementation that only hurts aging Americans and those that look after them," said Andrea Mercado, the campaign director at the National Domestic Workers Alliance.