The Lesson of War

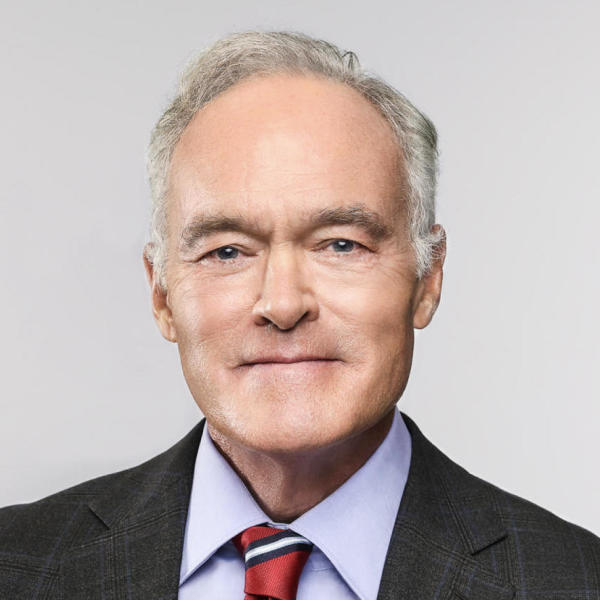

The following is a script from "The Lesson of War" which aired on May 3, 2015. Scott Pelley is the correspondent. Ashley Velie, producer.

The war began with the murders of three teenage boys. By the time it was over, more than 500 children were dead. For 50 days, this past summer, Israel and the Palestinians of Gaza fought their bloodiest war since 1967. And some of the images of the battle in our story tonight are hard to watch. Where the decades of suffering go from here depends not so much on a thousand threads of tangled talks but on one question that comes before all others. Can peace be taught to children who have learned only the lesson of war?

The first boy to die was wrapped in the grief of Israel. In June, the night his mother sat up worrying, 16-year-old Naftali Fraenkel and two friends were kidnapped, and later, shot by Palestinian terrorists.

Rachelle Fraenkel said the eulogy at a national service.

Rachelle Fraenkel: The eulogy was turning to my son and talking to him, and to the people that were searching so hard and that were praying so hard, and recognizing that we're going to live on with other blessings we have in our lives and that this is something we'll keep inside of us. It's how special he was to us.

The next day, Israeli terrorists kidnapped a Palestinian boy. Same age. Mohammad Abu Khdeir was burned alive. Within days, it was war.

And not in 50 years were so many children about to die in the Holy Land.

Palestinian rockets, plentiful but unguided, punched wildly into Israel, inflicting fear, but limited damage.

Israel struck Gaza with digital domination, blasting neighborhoods into seismic collapse. We flew a drone over part of Gaza to comprehend the scale.

The Palestinian Health Ministry says civilian deaths in Gaza came to 1,492. Six civilians were killed in Israel during the battle. Israel lost one child, Gaza lost more than 500.

Scott Anderson: If you look at the average 10-year-old child in Gaza today, they've been through now three large-scale conflicts and it's a pervasive climate of fear of the unknown of what's gonna happen next.

Scott Anderson cares for a quarter million children in Gaza in 252 schools. After 21 years in the U.S. Army he became deputy director of the U.N. Relief and Works Agency which has sustained Gaza with schools, homes, jobs and food for seven decades.

Scott Pelley: What is it like to be a child in Gaza?

Scott Anderson: Very difficult. They have no idea what it's like to have electricity 24 hours a day. They have no idea what it's like to have heating all the time. People have lost their family members. Their homes have been destroyed. Schools have been destroyed. That takes a toll on children.

During the war, his classrooms became kitchens and shelters for more than half a million Gazans. Some of the U.N. schools were attacked and this past Monday, a U.N. investigation found that Israel hit seven schools killing 44 people. But the U.N. also blamed Palestinian militants for hiding weapons in three vacant U.N. schools that were not hit.

Scott Anderson: This conflict is probably the most widely talked about, widely written about, and least understood conflict in history.

This history begins in 1947, when refugees from Israel's creation compressed into a strip 32 miles by seven. In 2006, Gazans elected a government led by Hamas which the U.S. says is a terrorist group. Israel responded by sealing the borders and bankrupting Gaza's economy. Hamas burrowed tunnels under the blockade for trade and terror.

This summer, Hamas attacked Israel to lift the blockade and Israel invaded Gaza to destroy the tunnels. Sixty-six Israeli soldiers were killed. But in the end, as usual, nothing really changed.

In Israel, air raid sirens are as familiar to children as the lunch bell. In Gaza, a new generation is rising on the ruin of the last. And neither child knows the other.

[Dr. Jim Gordon, session: Does it seem strange that I would work in Gaza and in Israel too?

Kids: Yeah.]

Dr. Jim Gordon is an American psychiatrist working both sides. He's a professor at Georgetown in Washington and director of The Center for Mind-Body Medicine. These Israeli kids spent the war scrambling for shelter. They can't or won't talk about it. But Dr. Gordon has another way in.

[Dr. Jim Gordon, session: Draw yourself with your biggest problem. What ever that means to you. OK, do you understand?]

Dr. Jim Gordon: They come in often frozen but then they do the drawing and the drawing is of a destroyed house, of bloody bodies in the street.

Only a few Hamas rockets were lethal, but 3,000 were launched and in Israel today their arc, on paper, hits targets of the imagination -- a home destroyed, the wounded in an ambulance. Rachelle Fraenkel's six surviving children were all within range.

Rachelle Fraenkel: Anybody that lives under missiles lives in terror. If you know you're five seconds away from needing to choose which child to lie over to protect or to grab to the shelter. You can't imagine what kind of life it is.

Dr. Jim Gordon: For these children, it's as if the bombs were still falling now. So they're just as anxious, they're just as likely to be aggressive, they're just as fearful and withdrawn. And the parts of the brain that are concerned with thoughtful decision-making, with compassion for others, are shut down. So you're, you're just, like, a scared animal in that state.

One scene these kids can't picture is Dr. Gordon just five miles away, in Gaza.

The kids in Gaza are wearing down the same red crayons. Azar Jendia, nine years old, shared her pictures with us.

Azar Jendia: This is the building where my father was bombed, it collapsed on my father and two uncles. Half of my father's head was gone.

Scott Pelley: Show me the next picture. This is you?

Azar Jendia: This is me. I drew myself inside a grave, a martyr next to my father.

Scott Pelley: And this is a coffin that you're in?

Azar Jendia: Yes.

Dr. Jim Gordon: They wish, "If only I had died, then the family would have been together, and we would've all been together." And they do wonder. And that's one of the things that our groups help them find out is, "Why am I here? Why was I spared? "

Three days a week, week after week, they draw, talk, draw again. After sketching their problem, they picture a solution. This came from a 9-year-old boy.

Dr. Jim Gordon: The solution to this pain and this loss is that he wants himself to become a martyr, a suicide bomber. And so what we see here is a suicide belt and you see it around his waist.

Scott Pelley: Who was he going to bomb?

Dr. Jim Gordon: Going to bomb Israelis. Going to bomb the people who killed his father.

That answer to, "What do you want to be when you grow up?," may be fatal to the future because of the inescapable demographics arising on every apocalyptic playground.

That's the thing that really gets you about Gaza is the enormous number of children in the neighborhoods. About two million people live in Gaza and it turns out about half of them are under the age of 18. A local university did a survey after the war and found that 20 percent of the kids witnessed a death in their family. Thirty-five percent saw destruction at or near their home and 40 percent are suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder.

We found these children in the remains of their home. They're the grandchildren of Ahmed Karim Audha.

The loss of his life's work has broken even his voice. Before the blockade Audha was a successful contractor. He built this home, in the Arab way, to hold all of his generations. His five sons lived here with their families. Fifty relatives in all, fled before the crosshairs settled and a missile vaulted from a helicopter.

He's saying, even the animals have better lives. Our suffering is worse. Can we not have a home to live in?

Scott Pelley: What is it like for the children to be living here?

Ahmed Karin Audha: He told us, things are worse after the war than during the war. They wake up in the middle of the night horrified. We don't know what's wrong with them but we try to calm them down.

Dr. Gordon told us, with enough time, about 80 percent can see beyond war. Azar, who colored herself dead, came through the therapy with a dream.

Azar Jendia: My wish is to become a heart doctor because after the war, a lot of people had heart problems so I want to treat them.

Scott Pelley: It looks like there are many people who need your help.

Azar Jendia: Yes.

Scott Pelley: How did you start to feel better? How did you get from the first picture to the last picture?

Azar Jendia: The doctors helped me change, helped with my problems and helped get the sadness out of my heart.

We don't want you to have the wrong idea about Gaza. While many neighborhoods were ground to powder, much of Gaza City is alive again and a recent poll shows that Hamas is still favored by a slim majority.

Scott Anderson's U.N. schools, for the most part, have returned to teaching.

Scott Pelley: What are the needs here right now?

Scott Anderson: The number one need is to find a way to lift the blockade and restore economic opportunity here in Gaza.

Scott Pelley: What's at stake?

Scott Anderson: The future's at stake. You know, there's been a lot of militant activity in Gaza since I've been here, a lot of rockets being fired, a lot of younger men joining the factions. You know, my personal opinion is that's more because of lack of opportunity than any great desire to fight and die. You know, if they had jobs, if they had stability, if they had families I think they're less likely to engage in that kind of activity but with unemployment at nearly 50 percent of the population in Gaza unfortunately the factions are the ones that pay.

Scott Pelley: One of the things that you said during the war was that maybe we can teach our children that we want to live in peace. How do you go about doing that?

Rachelle Fraenkel: I have no easy answer for that. My children, their brother was murdered by a Hamas terrorist. And it's very easy to let them grow up hating Arabs. And I make a point of not doing that.

Scott Pelley: A lot of people would forgive you...

Rachelle Fraenkel: Yeah, it's not a matter of forgiveness, it's a price you pay when you grow up on hate. It's not something I'm willing to pay. I want my children believing in a world that has a lot of good in it.

The price paid in a 68-year conflict is inherited as a debt, one generation to the next. The summer combat ended as it always does. Both sides buried their children and claimed victory.