Treating Ebola: Inside the first U.S. diagnosis

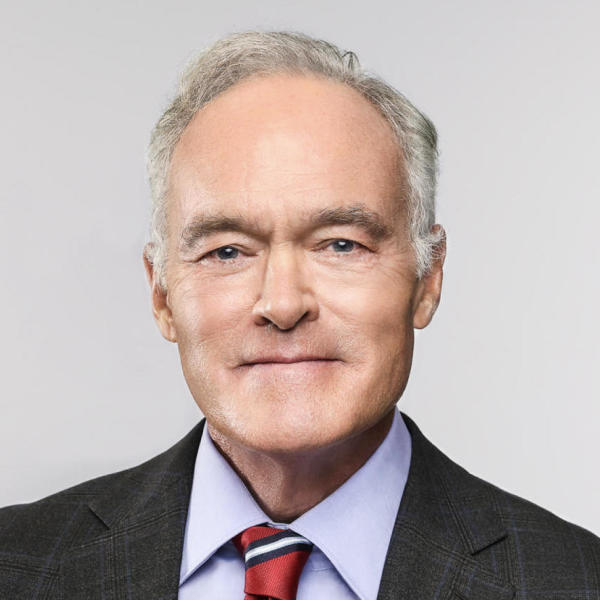

The following is a script of "Treating Ebola" which aired on Oct. 26, 2014. Scott Pelley is the correspondent. Patricia Shevlin and Gabrielle Schonder, producers.

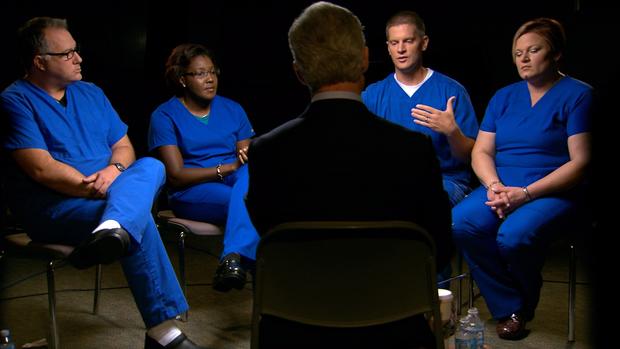

You've heard a lot about the Dallas hospital that treated Thomas Eric Duncan, the first Ebola patient diagnosed in America. But you've never heard what actually happened from the people who fought for his life at the risk of their own. You're about to meet four nurses who treated Duncan from the time he came into the emergency room, to the moment that he died. The staff had been blindsided by a biomedical emergency that burst into their ER like a wildfire. Contrary to reports that the hospital bungled the response, the story the nurses tell sounds more like a heroic effort to stop an outbreak. On September 28, Duncan was rushed by ambulance to Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital. He was isolated in a separate section of the ER and nurse Sidia Rose, starting the night shift, was briefed on the special precautions required for what they now suspected was a case of Ebola.

Sidia Rose: I went over and met with a nurse who gave me a report. She also went over the protective gear that we would be wearing that night. She gave, you know, finished briefing me on what was going to happen, and I literally burst out in tears.

Scott Pelley: Why?

Sidia Rose: It's very scary. I know about Ebola, and the only reason I do, it's because I've been just researching it on my own. Since January, I kept hearing the word popping up in the news. And I just wanted to find out about it.

Richard Townsend: When our supervisor said that we had a potential Ebola case, I don't want to call it calamitous but there was a lot of concern, people became very vocal, understandably it's the boogie man virus.

Emergency room nurses Richard Townsend and Krista Schaefer made sure that Rose was suited up properly. As per the hospital's protocol, she worked with Duncan alone, with Townsend watching over her.

"I got myself together. I'd done what I needed to get myself prepared mentally, emotionally, and physically, and went in there and did what I was supposed to."

Scott Pelley: When you went to approach Mr. Duncan for the first time, what did you do? How did you prepare for that?

Sidia Rose: I gathered myself together. I put on my protective wear and I went in and introduced myself to him and you know just let him know that I would be the nurse helping him tonight.

Scott Pelley: What were you telling yourself?

Sidia Rose: I was very frightened. I was. But and I just dried my tears, rolled down my sleeves, so to speak, and went on about my night.

Scott Pelley: But why do you go in there? Why don't you say, "You know, this one's not for me"?

Sidia Rose: As a nurse, I understand the risk that I take every day I come to work and he's no different than any other patient that I've provided care for. So, I wasn't going to say, "No, I'm not going to care for him."

Scott Pelley: But you were risking your life to take care of this patient.

Sidia Rose: Oh, I know that. And that's why I, as frightened as I was, I didn't allow fear to paralyze me. I got myself together. I'd done what I needed to get myself prepared mentally, emotionally, and physically, and went in there and did what I was supposed to.

Though Duncan's test results wouldn't be known for two days, she was certain she was witnessing Ebola.

Sidia Rose: The first time when I went in and he vomited, I was standing in front of him, he was sitting on the commode, and there was just so much it went over the bag, it was on the walls, on the floors. I had two pairs of gloves on and shoe covers. And I had my face shield on. I didn't have two masks on at the time, I had just one. No, we didn't have any head covers. But I wiped down the walls, wiped down the floor with some bleach wipes.

Richard Townsend: He was having so much diarrhea and vomiting that he, you know, she was constantly having to give him the little bags that we have for people to vomit into.

Richard Townsend: All of that was hazardous waste and it had to be bagged and then double bagged and then put into a separate container that could then be disposed of later. Because anything that has any of his bodily fluids on it has the potential to be lethal to somebody else.

"And that's when he said to me his family had suffered a loss. That he had buried his daughter who had died in childbirth."

Eric Duncan was 42 years old, from Liberia, which is ground zero for this outbreak. Half of all the cases in the world are in Liberia. He flew to Dallas to visit family, became sick a few days later, and then made his first visit to the Dallas hospital.

It was the night of September 25 when Duncan first came into this emergency room. According to the hospital records, he had a temperature of 100.1. Over the course of the four hours or so that he was here, his temperature spiked to 103, but then it dropped back down. Again, according to the hospital records, he told the staff that he had come from Africa, but did not specify West Africa or Liberia. About three o'clock in the morning, with his symptoms not very severe, the staff decided to send him home with antibiotics.

But three days later he was back in the ER gravely ill and about as contagious as he would ever be. The virus is not transmitted though the air but physical contact with a single viral particle can cause infection. The hospital notified state health authorities immediately. And they wanted Sidia Rose to ask several urgent questions of Duncan.

Sidia Rose: I explained to him, "We are under the impression that you may have been exposed to Ebola. And I said, "Where are you from?" And he told me Liberia.

Sidia Rose: And I asked, "Have you been in contact with anyone who's been sick?

Scott Pelley: He said?

Sidia Rose: No. He said no.

State and federal health officials wanted to know if Duncan had been with anyone who had died in Liberia.

Sidia Rose: And that's when he said to me his family had suffered a loss. That he had buried his daughter who had died in childbirth.

But nurse Rose says Duncan told her it wasn't Ebola that killed his daughter. Rose told us that she reported this to the Texas Department of Health, but then Duncan denied his own story when he spoke to those officials.

Scott Pelley: What information was it that he denied to the health officials?

Sidia Rose: About his travels, about him burying his pregnant daughter who had died in childbirth. He denied that. He said that's not true.

Scott Pelley: So he wasn't honest with them.

Sidia Rose: Yeah.

"And we held his hand and talked to him and comforted him because his family couldn't be there."

This is nurse Richard Townsend, who dressed in the protective gear that was recommended by the CDC at the time, just as Sidia Rose did.

Scott Pelley: Was any of your skin exposed?

Sidia Rose: At that time it was just a gown that I was wearing, so yeah. Not my hands, not my legs, my face, I had my face shield on, the mask with the face shield.

Scott Pelley: So your neck was exposed?

Sidia Rose: Yes.

Scott Pelley: So the CDC protocols that you would've looked up the day he came into the emergency department was in your estimation deficient?

All: Yes.

On September 29, Duncan was carried from the emergency department to intensive care. Nurse Nina Pham, who was involved in the transfer, would become the first person to catch the virus in the United States.

It took 48 hours to get Duncan's positive test results. And by then the hospital, on its own, had equipped the staff with suits that allowed no skin to be exposed. It would be another three weeks before the CDC made this its new standard. Then the hospital moved out all of the patients in medical intensive care and reconfigured the 24-bed unit for just one patient. It was a strange scene for ICU nurse John Mulligan.

John Mulligan: By the time I came in, they had already received the Tyveks, the pappers. So we had the full hazmat gear that people are used to seeing.

Scott Pelley: Is this the full suit?

John Mulligan: This is the full suit, yes. There were always two of us in the room at all times. And we were designated two people to be in there. I've been in health care for nearly 20 years and I've never emptied as much trash as just from the waste of his constant diarrhea that he was having was remarkable. And we had these longer surgical type gloves on. They were taped to the Tyvek suit, full headgear with a circulator with a HEPA filter that would plug into the back. And the first time I got out of that suit, it literally looked like someone had pushed me into a swimming pool. I was drenched.

They were working 16 to 18 hour days, spending two hours at a time in Duncan's room.

John Mulligan: And we held his hand and talked to him and comforted him because his family couldn't be there.

Scott Pelley: You held his hand through the spacesuit?

John Mulligan: I did. He was glad someone wasn't afraid to take care of him. And we weren't.

"We asked for volunteers. Everyone volunteered."

Richard Townsend: I have nothing but respect and admiration for everyone that was involved in his care you know everyone has someone in their lives that they love and they care about. I have a five-year-old and a three-year-old and my wife is pregnant. And the mortality rate for pregnant women with Ebola is, it's essentially 100 percent.

Scott Pelley: But Richard, why don't you go to the administration and say, "You know, I'm sorry. But my wife is pregnant."

Richard Townsend: People were allowed to request not to be tasked with his care.

Krista Schaefer: We asked for volunteers. Everyone volunteered.

Scott Pelley: Everyone was a volunteer, everyone that was there wanted to be there?

Krista Schaefer: Every person, housekeeping, respiratory, physicians, nurses.

But despite all the volunteers Duncan grew worse. An experimental drug wasn't helping.

John Mulligan: Early Saturday morning he had become very critically ill and was placed on a respirator.

Scott Pelley: He was intubated.

John Mulligan: He was intubated.

Scott Pelley: Tube down his throat?

John Mulligan: Tube down his throat, he had a dialysis catheter placed because he was not making any urine, but he needed to. I was in charge on those two days and came back on October 8 and was the primary nurse again. He was heavily sedated and he had tears running down his eyes, rolling down his face, not just normal watering from a sedated person. This was in the form of tears. And I grabbed a tissue and I wiped his eyes and I said, "You're going to be okay. You just get the rest that you need. Let us do the rest for you." And it wasn't 15 minutes later I couldn't find a pulse. And I lost him. And it was the worst day of my life. This man that we cared for, that fought just as hard with us lost his fight. And his family couldn't be there. And we were the last three people to see him alive. And I was the last one to leave the room. And I held him in my arms. He was alone.

"I would have nightmares, and still do, of my co-workers being infected and not being able to get to a hospital and treatment and dying."

Scott Pelley: Sidia, you spent perhaps the most time talking with Mr. Duncan and I wonder what you think people should know about him.

Sidia Rose: He was very kind and very appreciative. Even something as simple as me just giving him cold washcloth to cool his face down because his fever wasn't breaking, even that he was grateful for. He told me thanks.

Within days of Duncan's death, nurse Nina Pham was admitted to the hospital with Ebola.

Scott Pelley: When Nina became sick, that must've sent a lightning bolt through the staff because now it's one of you.

John Mulligan: I thought someone was playing a cruel joke until I finally looked at my phone and saw the missed text messages and the voicemails and turned the news on and went, "Oh my goodness."

Then four days later, nurse Amber Vinson fell ill. Both nurses have since recovered; this is Nina Pham leaving a hospital on Friday. But many on the staff still wonder whether they could be next.

Scott Pelley: Are any of you, all of you, still self-monitoring for signs of infection?

Sidia Rose: I am.

Scott Pelley: You are? You're still within the 21-day window?

Sidia Rose: For Mr. Duncan I'm passed my 21-day period. But for Nina Pham I'm still being monitored. I've been asymptomatic. My temperature has been rock solid.

Those who contract the virus are not infectious until they actually become sick. Members of the medical staff must take their temperature now twice a day and show the reading to a state health official. But, in at least one other way, the effect of fighting this virus could linger.

John Mulligan: I would have nightmares, and still do, of my co-workers being infected and not being able to get to a hospital and treatment and dying. And so it's like any traumatic event, this too shall pass. It's just going to take a little time.