Child's encounter with a bat may have sparked the Ebola outbreak

Where and how did the deadly Ebola outbreak begin? The disease that's killed more than 7,800 people across West Africa may have taken hold after a chance encounter last winter between a 2-year-old boy and wild bat in a hollowed-out tree.

New research published Tuesday in the journal EMBO Molecular Medicine provides an almost cinematic theory about the origins of the current Ebola outbreak, and also offers new evidence that a certain type of bat may play host to the deadly virus.

The study traces the activities of Ebola "patient zero," a 2-year-old boy in Méliandou, Guinea, who's believed to have been the virus' first victim in December 2013.

The researchers visited the village and neighboring areas, and learned from the residents that children liked to play in a hollow tree that was home to insect-eating free-tailed bats (Mops condylurus). These large fruit bats migrate annually to southeastern Guinea to the region of Kéléma, where Méliandou is located.

Previously, experts suspected that bush meat hunted and consumed by villagers might be the source of transmission. But the researchers say the child's father was not a hunter, and they did not find evidence that larger mammals were associated with the spread of the virus.

"In contrast, bat hunting was commonly described in the region," the researchers write. "Men of Meliandou and six other neighboring villages reported opportunistically hunting fruit bats throughout the year. Insectivorous bats were reported to be commonly found under the roofs of houses and similar hides in the villages. These bats are reportedly targeted by children, who regularly hunt and grill them over small fires."

The researchers examined wildlife surveys, conducted interviews with residents of the village and analyzed animal specimens and environmental samples such as soil.

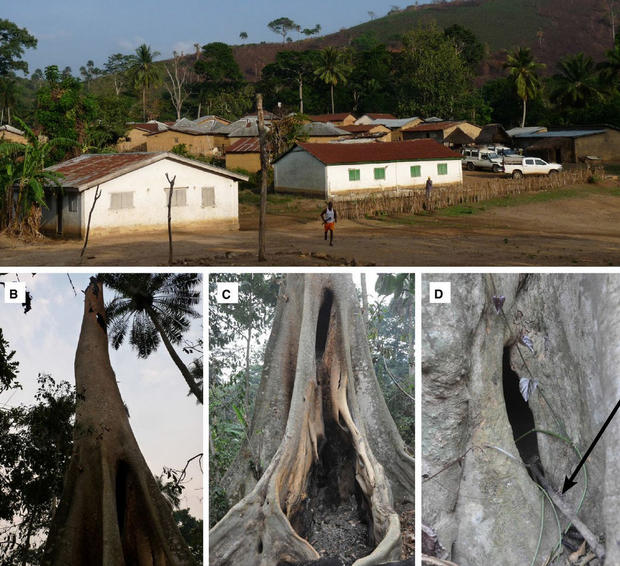

They spent eight days in Méliandou, a small village of 31 houses with surrounding farmland and large trees. The researchers found a large tree stump 50 meters from the home where "patient zero" resided, and villagers reported that children often played in the tree before it was cut down and burned. The stump lay next to a footpath frequently used by women of the village who head to river to do their washing.

The tree caught fire on March 24, 2014; some villagers reported seeing a "rain of bats" escape, and a large number were collected for food. Health officials in Guinea have speculated that bats are linked to the outbreak. In March, Guinean officials banned the consumption of bat soup and grilled bats.

According to the researchers, free-tailed bats are believed to have been linked to previous, smaller Ebola outbreaks. The animal has also been associated with the Marburg virus, which shares many similarities with Ebola. Bats have been singled out for their ability to host zoonotic viruses, which are able to make the jump from one species to another.

Viruses such as Ebola are believed to spread more easily as a result of deforestation, which increases the opportunity for infections crossing from wildlife to humans. Then, more mobile human populations carry the virus between towns and from rural forested areas to urban centers.

That is why the researchers say outreach from public health officials is now more critical than ever.

"Health education initiatives should inform the public about the disease risk posed by bats," they write. But exterminating the bat population is not an option. "These animals perform crucial ecosystem services with direct and invaluable benefits to humans," such as eating mosquitoes that cause malaria, which kills thousands in West Africa each year.