Budget cuts threaten rollout of earthquake early warning system

In an earthquake, having the latest information could be key to survival.

At the "quake cottage" in Burbank, California, scientists are working to warn people before earthquakes hit.

The facility is home to a state-of-the-art quake simulator where you know exactly when the shaking is going to start.

But what if you could get a warning before the real thing? Well, it does exist. It's called ShakeAlert, reports CBS News' Carter Evans.

Its rollout had been set for next year. Now, those plans, and the lives it could save, could be in jeopardy.

In an earthquake zone every second counts. Early warning systems are already operational in Mexico and Japan. Prior to a massive 9.0 quake in 2011 people in Tokyo got a quake warning of more than 60 seconds.

Now the Los Angeles rail system is, literally, on track with its own early warning program.

When an alert sounds during a simulation at the rail operations center, supervisors immediately bring all 83 trains in the system to a stop and then take cover themselves. In a real world scenario this all would have happened before the shaking began.

"When it takes about 12 seconds to stop a commuter train or about 10 seconds to take an elevator to the closest floor, or even just three seconds to get underneath a desk, you can save a lot of lives," said Josh Bashioum, founder of Early Warning Labs, one of just a few companies approved by the U.S. government to send out advance earthquake alerts.

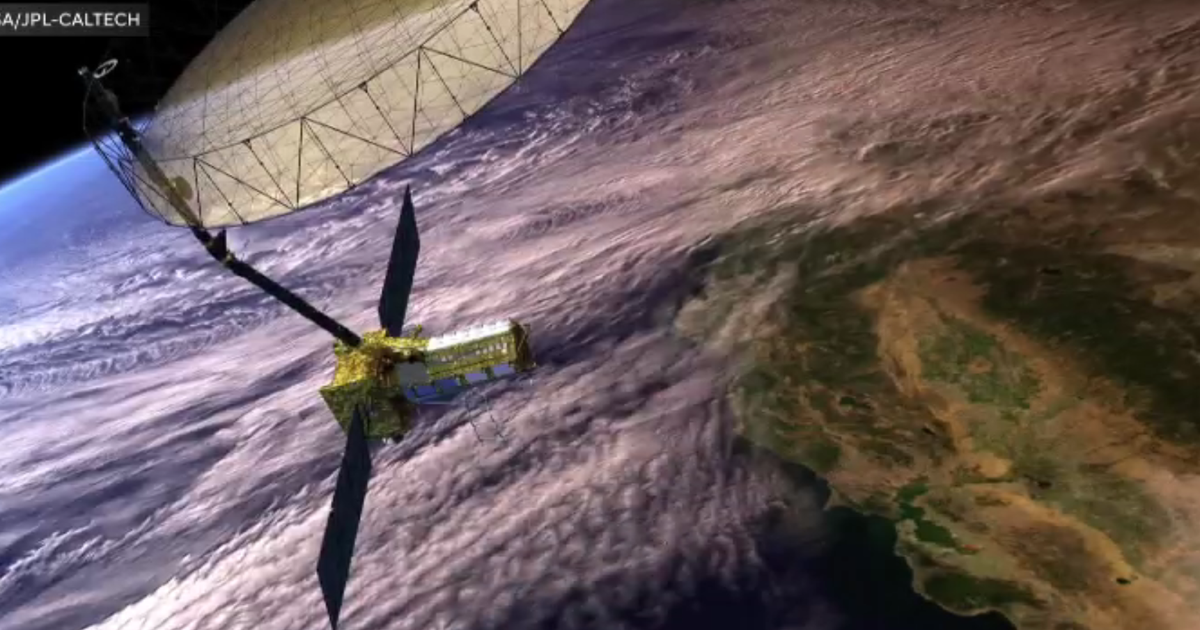

During an earthquake, seismic waves radiate from the epicenter like waves on a pond. Currently more than 700 sensors - most of them in Southern California - detect those waves, passing along data that can be used to predict when shaking will start in nearby cities.

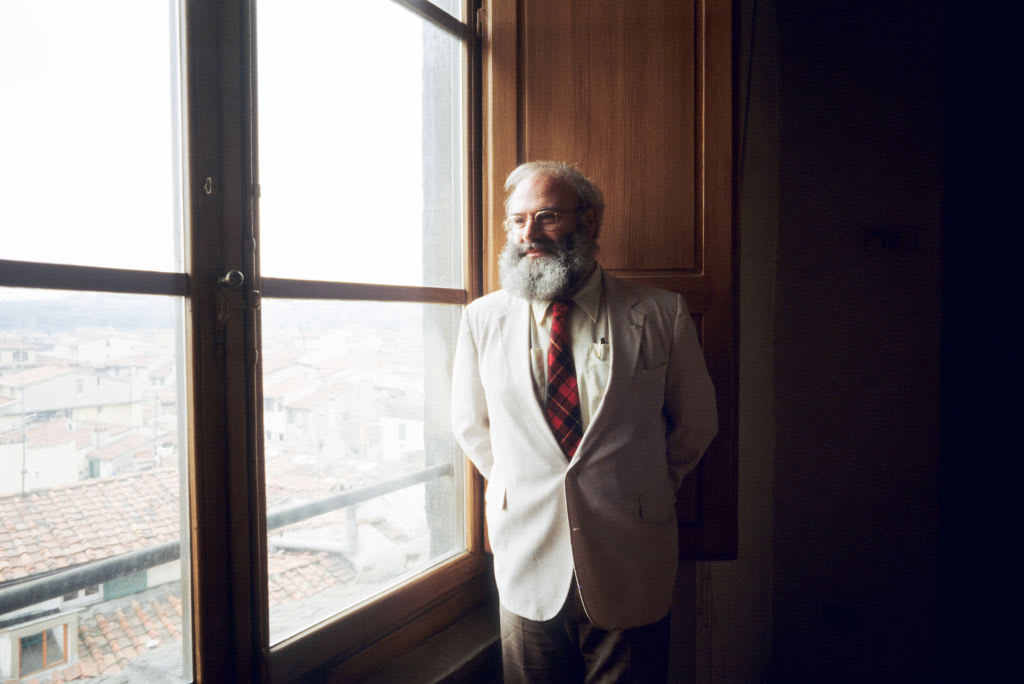

Seismologist Lucy Jones helped develop the early warning system for the U.S. Geological Survey. It still needs nearly a thousand more seismic sensors across the West. But that plan is now in jeopardy.

"If the president's budget is passed by Congress, the program will be stopped because this is one of the things being eliminated," Jones said.

Jones and others hope it doesn't take a disaster to convince lawmakers to keep the program alive.

"Japan started their program after 5,000 people died in Kobe. Mexico started their program after 10,000 people died in Mexico City," Jones said. "We are trying to be the first country to do it without killing the people first."

If the budget is cut, that means large parts of Northern California, Oregon and Washington, where more sensors still need to be installed, will not get an early warning when an earthquake hits.

Ultimately, the goal is to send an earthquake alert to every cellphone in a quake zone.