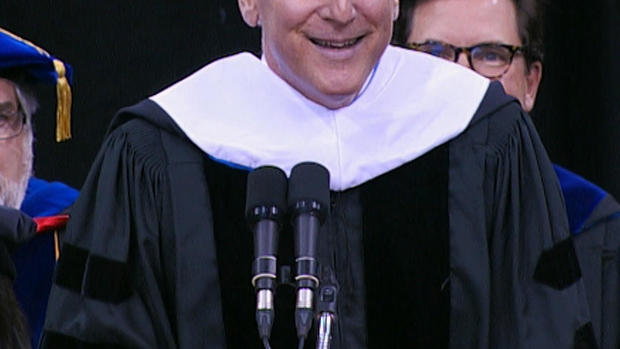

Dr. Jon LaPook on what it takes to be a "true healer"

Dr. Jon LaPook is the CBS News chief medical correspondent, a professor at the NYU School of Medicine, an internist and gastroenterologist at NYU Langone Medical Center, and the Director of the NYU Langone Empathy Project. He delivered the 2017 commencement address to the first graduating class of new doctors from the Quinnipiac University Frank H. Netter, M.D., School of Medicine — sharing lessons he's learned from the worlds of medicine and journalism. Here are his remarks.

I'm so honored to be here today, giving the inaugural commencement address. I want to thank President John Lahey, Dean Bruce Koeppen, and Don Weinbach for inviting me, and I congratulate them, Provost Mark Thompson, the other members of the platform party, and all of you for reaching this historic milestone.

I thought you might want me to talk about what I've learned from blending medicine and journalism. If I'm wrong, I'm sure I'll find out soon enough from today's Quinnipiac graduation exit poll.

I work in two worlds. Thirty-seven years ago, I graduated from medical school. Eleven years ago, I started as a correspondent for CBS News. But I continue to love medicine and still see patients.

I want to make sure you leave here today with at least one piece of advice that will help you be a better physician, will set you apart from the pack, no matter what specialty you enter. I'll tell you one story from each world, then leave you with a single piece of practical advice I've learned from doing both jobs.

Since the Hippocratic Oath outranks the Nielsen ratings, I'll start with medicine.

At this moment, you are about to become a doctor. When I was in your shoes, I remember thinking that every test, every paper, every minute of studying since kindergarten had led to this one enormous achievement: a medical degree. So breathe it in. But you are not doctors yet. At this delicious moment, breathe that in, too. Remember what it can feel like to be a patient: the mixture of emotions, from helplessness to embarrassment to fear. I know you've been studying for years to learn the science of medicine, but today I'm also asking you to consider the art of healing. Don't let all those facts and figures crowd out your ability to connect with your patients. But how in the world do you do that—especially during your internship and residency, when you'll be multitasking, tired, and just trying to keep your head above water?

It starts with a decision about the emotional wall we all build between ourselves and our patients. Constructing it is tricky. You don't want to make it too thin and porous, because that can be emotionally devastating. But you don't want to make it too thick and impervious, because then you miss out on all the good stuff, the precious moments when you connect with a patient as a person. I treasure the time an elderly patient showed up for an office visit on a beautiful spring day, and I wheeled her over to the Central Park Zoo to watch the sea lions. No medicine I have ever prescribed has had a more powerful therapeutic response.

Everybody has to find a comfort level. For me, erring on the side of "too empathetic" is the way to go. Patients pick up on it, and if they feel you really care, they're more likely to open up to you.

When I was a third-year medical student rotating through psychiatry, I saw an 8-year-old girl referred by the school psychologist. My preceptor and I met her in clinic once a week, but we couldn't figure out what was going on. For some reason, during the last visit of my rotation, I asked her mother, a single mom—I can still see her smile—what she would do when her daughter, the youngest of three, grew up and left home. She said, "Oh, I'll jump that bridge when I come to it." The words were almost around the corner—in fact, my preceptor went right on to the next question—when I interrupted him and said, "You know, you just said 'I'll jump that bridge when I come to it,' and the expression is I'll cross that bridge when I come to it. Are you upset about the thought of one day being alone?" Her smile evaporated and she started crying. She was not only depressed, which helped explain what was bothering her 8-year-old daughter, but she was suicidal, and we immediately arranged for treatment. That moment was simultaneously the most exhilarating and the most terrifying moment of medical school. What if I had missed it? What if we had just gone on to the next question? What had I already missed with other patients? And what was I going to miss in the future?

Here's the point. Here's a piece of advice that will set you apart: When we're watching a movie and an important moment is about to happen, how do we know? Because there's a close-up and the music changes. Well, in life, there's no close-up and there's no change of music. You have to play the soundtrack in your own head. You have to control the zoom button yourself. You must catch that moment when the patient—consciously or unconsciously—tells you what's the matter. You need to get them to open up to you as one human being to another. And they will not do that unless they know they are talking to a human being!

Now part two. Journalism and medicine go together well. There's a lot of overlap between what I do as a journalist and what I do—and you will do—as a physician: communicate. It doesn't matter if it's to one person or millions. Our job is to explain things clearly and provide perspective based on the most reliable information available. It's easy to slip into medspeak. But, believe me, not everybody knows what a cohort is, or a subset. Instead of "contraindicated," how about just saying, "not a good idea?"

These days, there's a lot to explain, and it's tough to do that if you have only 15 or 20 minutes with a patient. The key is taking complex topics and presenting them in simple, accessible terms. So communicating clearly—and succinctly—is an important skill. Work on it.

Your patients will look to you for guidance concerning what they should and should not worry about, and that's where staying up to date will be crucial. I did 66 segments about Ebola—we counted—and the message was the same every time. Ebola was a huge problem in West Africa, but the odds of it spreading widely in the United States were extremely low.

I'm more concerned about Zika, and have been saying that on air, over and over, for a year, including in a "60 Minutes" piece last fall. It's the first mosquito-borne virus ever known to cause a birth defect, including microcephaly, and the first mosquito-borne virus to be sexually transmitted. I've covered this story in Brazil, Puerto Rico, and—two weeks ago—in south Texas. With a vaccine not expected until next year, at the earliest, it seems inevitable the virus will spread further in the United States, especially to mosquitoes along the Gulf Coast. But people are still not aware enough about the risks, and about how to protect themselves. This is a perfect example of where I can help by talking to a large audience, and you can help by talking to your patients and friends. And with especially complicated issues like Zika, point them to reliable online information, like the CDC website.

My experience in journalism has helped me see how we—as doctors—can make a difference beyond what we might imagine.

Three months after the terrible 2010 earthquake, I was in Port-de-Paix in northern Haiti—the poorest part of the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere. I was in a one-room combination delivery room and neonatal ICU. To my right was a premature baby boy, clinging to life with the help of the one portable oxygen machine on hand. To my left was a woman in labor. Suddenly, the unborn baby's pulse dropped. After a few minutes, the oxygen machine was wheeled from the premature baby to the woman in labor, who delivered a healthy girl. The premature baby died. In the United States, that baby would have had more than a ninety percent chance of survival.

You certainly don't have to go to Haiti to see health care inequity. You find it throughout the world and across the United States—disparities in outcomes based on factors like race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status. I won't quote facts and figures: You've undoubtedly seen them already. But I'd like to convince you that you can make a difference here. You have that power. And it doesn't have to be on a grand, policy-level scale—although that would be nice!

You don't have to be Dr. Paul Farmer, a co-founder of Partners In Health, who helped build a modern hospital in central Haiti that opened two years after the earthquake. Oxygen outlets in the walls by every bed, for the next premature baby. You can make a difference, one person at a time, in your own community.

But, of course, we do need large-scale, public health and policy solutions to health care inequity. Please keep your eyes open so you recognize it—whether in your practice or in some far off place. Think about what you can do to help. And triage this as "stat."

And now this: a single piece of advice based on what I've learned in both fields, as a physician and a journalist. Be comfortable with uncertainty. If you've been practicing medicine for five years and you think you have all the answers, you're in the wrong profession. Patients get understandably frustrated when one year we say one thing, and the next year it appears we're saying the exact opposite—whether it's about postmenopausal hormone replacement, mammography, PSA screening, or whatever. But YOU shouldn't be frustrated. Medicine has always been about trying to think logically, based on the best available data. And thank goodness that data changes. For thousands of years, holes were drilled into the skulls of patients to release evil spirits, and people were bled to help restore the correct balance of "bodily humors." What are we doing now that doctors a hundred years from now will look back at and think, "Can you believe they used to do that? Antibiotics for infections? Didn't they know about drilling a hole into the skull to release the evil spirits?" Don't laugh; we're using leeches again, not for bloodletting but to help improve microcirculation and wound healing.

All this should actually take the pressure off. You may be thinking, "Do I really know enough to be a doctor?" I certainly had that question. Well, you DO know enough—and there will be supervision! Your colleagues and teachers are there to help. And you have the foundation: a knowledge of anatomy, pathophysiology, all the basics. After that, no matter how many facts you've memorized, it's still only a tiny fraction of all medical knowledge. So relax. Practicing medicine is open-book. You have a ton of electronic medical information at your fingertips, and you're going to have the fun of learning something new every single day.

And you're allowed to say, "I don't know"—an especially good idea when you don't know.

What's going to distinguish you as true healers is the way you embrace humility, compassion, and empathy. Turn away from the computer screen and look your patient straight in the eyes. Understand the extraordinary importance of listening. And realize that even when you don't have the answer for a patient in need, you can still help—with a sympathetic ear, a reassuring touch of the hand, and by sticking by them, through sickness and health.

Congratulations!