Diagnosis: Autism

The government recently announced that autism now occurs in about one of every 150 American children—a new number that is adding to what was already a raging controversy: with parents groups arguing with scientists over what causes autism, and with politicians over funding for research.

In the meantime, behavioral scientists are trying to identify the early symptoms so that a diagnosis can be made by the age of one. As correspondent Lesley Stahl reports, today most children are left undiagnosed until they’re five years old.

Researchers at the M.I.N.D. Institute at the University of California in Davis believe, if they can catch it early, they can change the way a child’s brain develops. They have started testing their theory in toddlers like Christian Heavin.

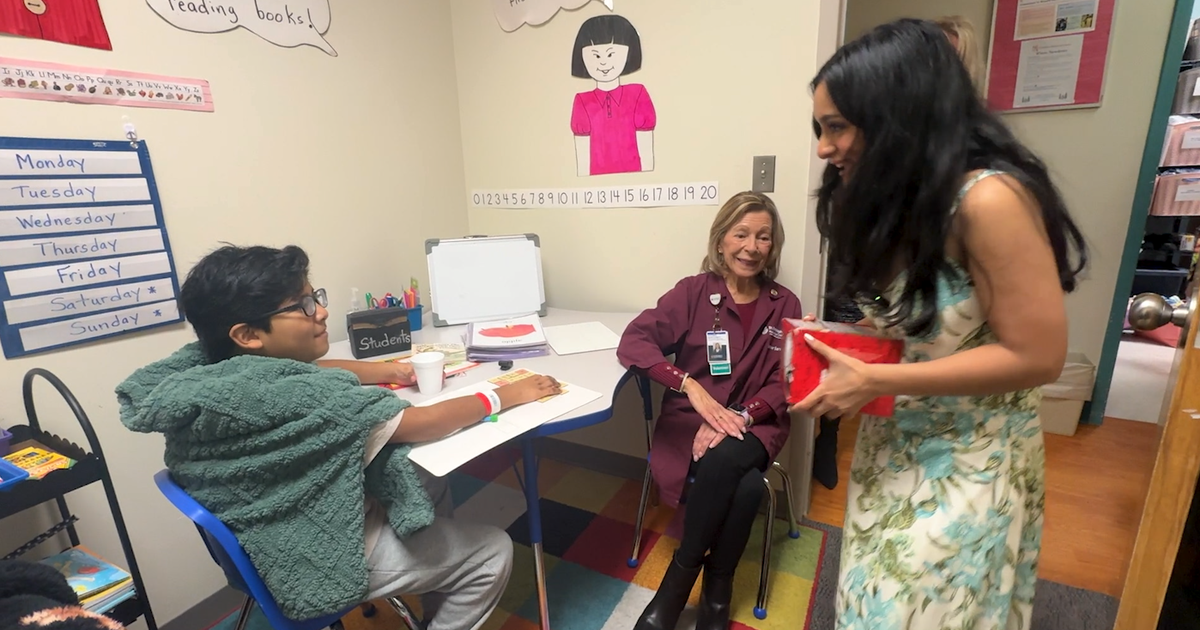

Psychologist Sally Rogers, a pioneer in the field of autism treatment, started giving three-year-old Christian intensive therapy about a year ago, hoping to alter the course of his autistic behavior.

Asked what his behavior was like before she met him, Rogers says, “Well, when we first met Christian he didn’t have any words.”

“He didn’t really have any play skills. He mostly threw things on the floor,” she adds.

And she says he would throw 20-minute temper tantrums because he couldn’t communicate. “He was really out of control,” Rogers says. “They had to bolt the furniture to the walls because this two year old was in danger of pulling furniture down on himself.”

Dr. Rogers worked with Christian one on one—on her hands and knees, in his face, teaching him new words and forcing him to interact with her.

She believes that if treatment can begin this early, while a child’s brain is still malleable, the results can be dramatic.

“Do you think that you’re actually re-wiring the brain? Do you think you’re setting up new wires that wouldn’t be there?” Stahl asks.

“I think we certainly are creating new connections in the brain. That’s what learning is,” Rogers explains.

Asked if she is suggesting that autism can be cured, Rogers says, “We don’t know how to touch the biology of autism. But I do think that the behaviors that are associated with autism can be reduced to the point where they’re not obvious anymore.”

“Now, you can’t make that promise to everybody, can you?” Stahl asks.

“No, you sure can’t. There’s a huge range of severity in autism. There’s a huge range of reactions to treatments,” Rogers acknowledges.

Christian is now able to talk with his mother Jennifer, and even a stranger like Stahl, in multiple word sentences.

Valerie Arias often wonders what her 13-year-old son Teddy’s life would be like if his autism had been treated earlier.

“When Teddy was about six months old, I had him in his car seat, and he just kept flailing his arm over his head,” she remembers. “My mother looked at him and she was like, ‘Val, I think Teddy has autism.’ At six months old, my mother told me that my son had autism. And I said, ‘No, he doesn’t. There’s nothing wrong with my baby.’”

“I was very angry at my mother,” she adds. “I didn’t speak to her probably for about a year.”

What her mother saw was that Teddy never babbled as a baby—he just screamed and grew increasingly violent.

Valerie may have been in denial, but even doctors didn’t diagnose Teddy’s autism until he was four years old.

By that time, Michael, who is now nine, had been born. In all, she and her husband Aaron have four children, including Paige, 14, and one-year-old Haydn.

Right after Haydn was born, Valerie heard about a study at the M.I.N.D. Institute on early detection of autism. It was focusing on so-called “baby sibs,” children like Haydn with an older autistic sibling. So she signed him up.

“Did you know at that point that autism did run in families, does run in families?” Stahl asks.

“I knew that the chances of having another child with autism were greater,” Valerie tells Stahl. “But, I figured since Michael didn’t have it that everything was okay.”

When psychologist Sally Ozonoff, vice chairman of research at the M.I.N.D. Institute, started the study three years ago, she was hoping to drastically lower the age of diagnosis.

She says she is aiming for a diagnosis age of 12 months. Ozonoff is tracking 200 babies from birth, like Gabe, a normal 12-month-old, being tested for his reactions to a new toy.

“He’s very interested in it. And he communicates that to her with that great look, big eyebrows raising, smile. And then he asks for it without language—he’s ‘Ah, I want that,’” Ozonoff observes.

This behavior, Ozonoff says, is typical of a healthy one-year-old.

But when a boy named Jacob is shown the same toy, he stares at it in silence, never reaching for it, never looking up at the examiner.

“There’s no communication at all with the woman,” Stahl remarks.

“That’s right. It’s as if she isn’t there. Like she’s an object-handing machine,” Ozonoff says.

Jacob was later diagnosed with autism.

Ozonoff also uses high tech methods, like eye tracking. A normal baby looks right in mom’s eyes when she talks to him. But children who are autistic avoid eye contact, looking more at the mouth.

Like most autism researchers, Ozonoff believes children are born with the disorder. She went into her study convinced she would spot the symptoms as early as six months.

But so far, researchers have not been able to see the symptoms at such an early age.

Diagnosing one year olds has proved just as perplexing. Repetitive behavior, like the way Jacob plays with a lid for example, looks like a clear symptom.

“All he’s doing is the picking up and watching it wobble, over and over again,” Ozonoff observes.

But Ozonoff has found that not all one year olds who do this end up with autism. Her “most reliable” test so far is surprisingly simple.

“Starting about six months maybe even a bit earlier, if you say a child’s name, they quickly turn and look at you. And you’ll see this with Gabe,” Ozonoff explains. “Say his name, his head whips around…makes eye contact and smiles.”

When the same experiment was done with Jacob, the result was different.

“The experimenter’s gonna walk behind him. Call his name three times at normal volume,” Ozonoff explains.

Jacob didn’t respond to his name.

But even with this test, only half the children who fail it end up having autism. Haydn was six months old when he was first evaluated and, to Valerie’s relief, he tested on par with children his age.

On one of her visits last year, Ozonoff gave Valerie a copy of her book on Asperger’s syndrome, a high-functioning form of autism.

“So I was reading this book. And through the whole book I just cried because I felt like I was reading this book about Michael,” Valerie remembers.

Michael is her nine-year-old. Through years of speech and occupational therapy, no one had ever suggested that his problems, including his struggle to make and keep friends, could be Asperger’s, until Valerie began asking questions.

“So now you’re basically told you have two sons with autism,” Stahl remarks.

Valerie admits she was reeling. “I was. You feel like you should, you should have pulled your genes out of the gene pool a little sooner you know, at that point,” she says.

And there was still the question of Haydn: his 12-month visit a half-year later was distressing. He wasn’t smiling anymore and he seemed to be regressing into his own world. And then, he stopped responding to his name.

“I knew my son wasn’t hearing me. Everyone around me was saying, ‘Oh, he’s just stubborn. He doesn’t want to listen to you.’ But I knew that wasn’t it,” Valerie recalls. She says she knew it wasn’t a hearing issue.

Despite Haydn’s symptoms, Ozonoff felt it was still too early to tell.

“I would hate to cause the pain…and anguish of having another child diagnosed on the spectrum and then be completely wrong,” she explains.

More and more parents are worried about the chances of having an autistic child, with some autism groups saying there’s an “epidemic,” claiming a 60-fold increase since the 1970s.

Dr. Stephen Goodman, an epidemiologist at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, has reviewed autism statistics for the past 30 years. He says, “The explosive increase that has been claimed is almost certainly not true.”

“The numbers, if they’re rising, are not rising very quickly, if it’s going up at all,” he says.

There’s no question more children are being diagnosed with autism than ever before. But Goodman, other respected epidemiologists and autism researchers says that’s because of something that happened in 1994, when the definition of autism was greatly widened. Since then, Asperger’s syndrome and other brain disorders that were not included before have become part of the autism spectrum. On top of that, Goodman says there are no reliable numbers from the past to support claims of an exponential rise.

“Have you ever seen a 60-fold increase in any disease?” Stahl asks Goodman.

“Not that didn’t have a recognizable agent, like an infectious disease…like AIDS,” Goodman says.

Asked if there could be a hidden source, that has yet to be identified, Goodman tells Stahl, “Many people have looked very hard, and they haven’t found one.”

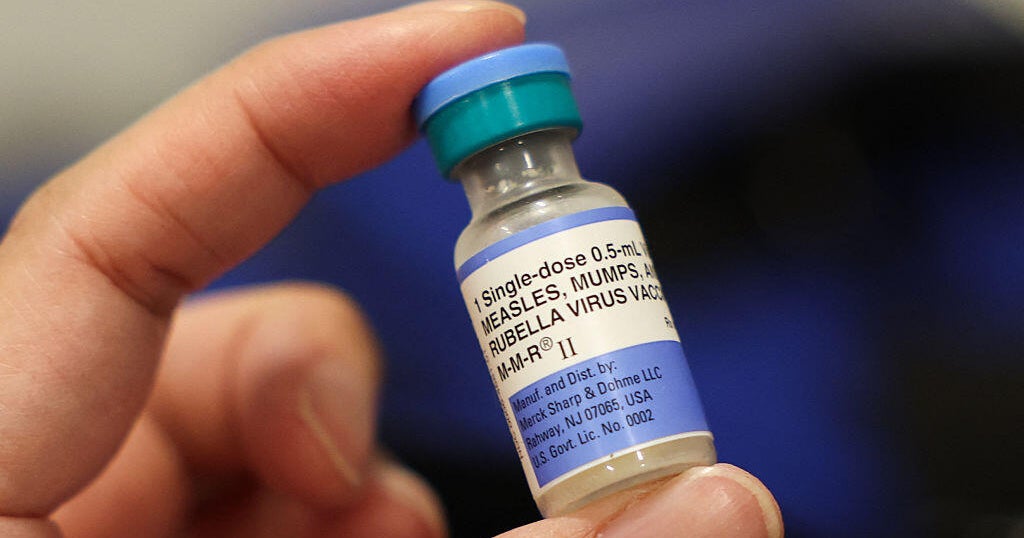

One hypothesis has been that the mercury in childhood vaccines causes autism, but Goodman himself served on a national medical panel that found no evidence of that, though more research is being done.

For researchers, like the M.I.N.D. Institute’s Sally Rogers, autism remains a daunting adversary.

Despite Christian’s gains from early treatment, children with more severe forms of the disorder often don’t make the same kinds of strides.

And Sally Ozonoff is not yet able to identify definitive, unmistakable early symptoms, although she still has 18 months to go in her study.

When Valerie brought her son Haydn back for another exam at age 14 months, Dr. Ozonoff and Stahl watched through a one-way mirror. After testing normal at six months, and showing symptoms at 12 months, Haydn had changed again.

He was making more eye contact and interacting with the examiner and he was laughing.

“This is very reassuring,” says Ozonoff.

But not entirely: it took three tries to get Haydn to respond to his name. And he became fixated on a lid, the kind of repetitive behavior that sets off alarm bells in Ozonoff.

With such a mixed picture, Ozonoff told Valerie it was too soon to call it.

“There are some encouraging signs, but there are some mildly concerning signs and what we really want to do is join with you to keep monitoring him as closely as we can,” Ozonoff says.

Asked how she is feeling, Valerie tells Stahl, “Well, I’m still leaning for optimism because, you know, he’s such a good boy. He’s a good kid.”

Valerie had hoped to know by now if she has a third son with autism. But Dr. Ozonoff says she probably won’t be able to tell her until Haydn turns two next October.

Produced By Karen M. Sughrue