Is the U.S. economy in danger of deflating?

Something unusual is happening. For the first time since the 2008 financial crisis, consumer prices are falling. Deflation, in a narrow but still dangerous sense, has come to the U.S.

The government on Thursday reported that the Consumer Price Index dropped 0.2 percent in January from the year-ago period, led by a 9.7 percent month-over-month decline in energy prices. Gasoline prices fell 18.7 percent last month.

As Japan's nearly two decade economic downturn shows, deflation can smother growth for years. Falling prices encourage consumers to wait for even lower prices, stifling sales and pushing down wages, making it harder for households and business to service their debt, which also becomes relatively more expensive.

For now, many economists, as well as the Federal Reserve, mostly discount the danger to the U.S. economy posed by deflation, which is now hindering Europe's growth. Indeed, after removing the impact of volatile food and energy prices, so-called "core" CPI rose at a 1.6 percent annual rate. That's low, but close to normal.

But the grave risks of deflation means it's important to stay vigilant, with some experts already sounding the alarm.

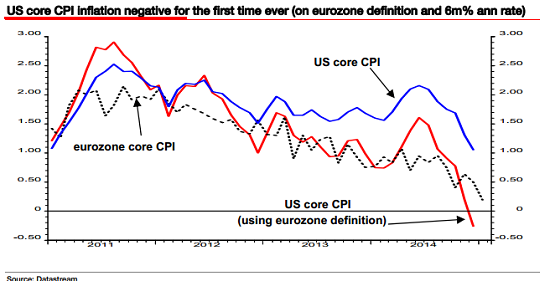

Societe Generale strategist Albert Edwards, known for his bearish outlook on Wall Street, focused on the threat in a recent note to clients. He compares what's happening in the U.S. to the deflationary environment in Europe, seeing symptoms of global economic slowdown.

If U.S. core CPI were measured in the same way eurozone prices are calculated (removing the effects of housing in addition to food and fuel) on a six-month annualized rate, we're actually in worse shape. This will be a shock to those just looking at the regular numbers, which has annual U.S. core inflation at 1.6 percent, compared 0.6 percent in the eurozone -- reflective, according to the consensus view, of the relative strength of the U.S. economy.

Edwards notes that the housing inflation calculation that goes into the headline CPI number is a made up number known as "owner-occupier equivalent rent," or OER. This is meant to measure the implied rent incurred by living in a home as a homeowner rather than renting it, the inclusion of which has been the center of some debate.

The measure has been rising to reflect the strong rise in rents last year, but it has since started rolling over. Additional weakness could reveal the true extent of the deflation problem for all to see and, in so doing, call into question the robustness of the U.S. economy.

The Fed, if it underestimates the threat, could make it worse by raising interest rates later this year. In her testimony to Congress this week, Fed Chair Janet Yellen said the central bank is "reasonably confident" that inflation will rebound. She pointed to the relative stability of measures of future inflation expectations, and explained away the recent collapse in bond yields -- as bond traders demand less and less inflation compensation -- as caused by other factors.

Maybe Yellen's optimism will prove prescient, especially with lower inflation boosting real wages for consumers. But the data is worrisome, suggesting that the economy is weaker than it seems. Growth this year could hinge largely on the direction of home prices this summer. Any move by the Fed to hike rates too soon could push up mortgage rates, hurt the housing market and push deflation down even more.

The value of the U.S. dollar and the path of commodity prices, especially crude oil, also bear watching. With energy companies mothballing a growing number of oil rigs, as crude prices stay slow, oil production and inventories should start falling later this year. That would likely stabilize prices and help snuff out the sparks of deflation.

It's energy's role in all this that has Peter Boockvar of the Lindsey Group unconcerned, noting that "talk of deflation is complete nonsense." as all we need to see is for oil prices to stop falling for "the consensus picture on inflation to change quickly."

Still, in the end, much depends on the Yellen Fed getting monetary policy right this year as the stakes just keep getting higher.