Last Chance

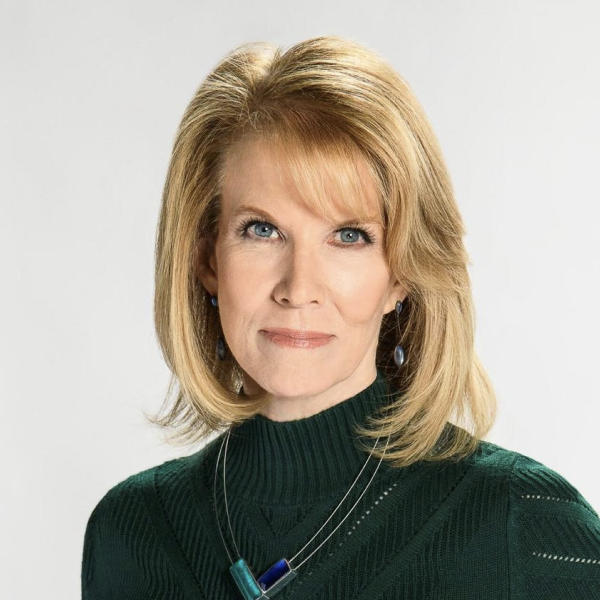

Produced by Gail Zimmerman

[This story was originally broadcast on March 24. It was updated on Dec. 6]

Like so many places along the banks of the Mississippi, Westwego, Louisiana, attracts strangers in search of work on boats and barges. It is why 22-year-old Damon Thibodeaux, who had come to town for a family wedding, stayed. He had been in town for only a month when Crystal Champagne was killed.

"These very high-profile cases, there's -- a great deal of pressure to ... get the case solved and ease the worried mind of the public," attorney Denny LeBoeuf told "48 Hours" correspondent Erin Moriarty.

Denny LeBoeuf remembers the day in July 1996 when Thibodeaux was arrested for murder.

"His picture was in the paper the next day. 'We got the guy that killed the girl,'" she said of the newspaper article.

The Champagne family had befriended Thibodeaux when he first arrived to the New Orleans suburb. He was a distant cousin whom they barely knew, says Crystal's mother, Dawn Champagne.

"He just seemed to be an ordinary person," she said.

"Was he ever inappropriate with your daughter?" Moriarty asked.

"Not that I ever noticed," Champagne replied.

"Did you consider them as part of your family?" Moriarty asked Thibodeaux.

"Yeah," he replied.

Thibodeaux was with the Champagnes on the hot Friday afternoon when Crystal said she was going to walk to the store.

"Had she asked you for a ride?" Moriarty asked Thibodeaux.

"Yes," he exhaled, seemingly troubled.

"And you said, 'No'?" Moriarty asked.

"I said, 'No'," Thibodeaux replied.

When Crystal didn't return, her mother panicked and called police.

Thibodeaux joined family and friends in a search all through the night.

"We check the park where she plays softball at. We check the shopping center -- ride around the neighborhood at -- you know, just lookin' for her," he said.

Twenty-four hours after Crystal went missing, police brought in Thibodeaux and others for questioning. He was still there when the case became a homicide:

Police Call: "Some people come walked over here a minute ago and they found a little girl dead by the river."

Crystal's body was found by a family friend near the levee in Bridge City, about five miles from her home.

"It's now a murder investigation. It's no longer a missing persons," said Thibodeaux.

And the conversation, he says, got rough.

"I was increasingly under the impression that I was not gonna be able to leave," Thibodeaux explained.

"Because they thought you had done it," Moriarty commented. Thibodeaux nodded his head in agreement.

Around 1:00 a.m., he agreed to take a polygraph.

"And what did they tell you? Did you pass it?" Moriarty asked.

"No, they said I failed it," Thibodeaux replied. "That's the point where I realized I was never gonna walk out of there."

Thibodeaux says he felt doomed as the grilling continued for another three hours.

"They kept askin' the same questions over and over and over and over and over and over again," he said.

Finally, he says, he was too exhausted to take anymore.

"What did you tell them?" Moriarty asked.

"Whatever they wanted to hear," Thibodeaux replied.

He told investigators that he had found Crystal at the store and drove her to the levee. When she resisted having sex with him, he said he killed her:

Officer: What did she do?

Damon Thibodeaux: She started to fight.

Officer: When you left, how was she laying?

Damon Thibodeaux: Face down.

"But you're confessing to a rape and murder," said Moriarty.

"They were not gonna let me go until I did it," Thibodeaux replied.

Hours later, when Thibodeaux met with an attorney, he denied having anything to do with Crystal's death, but he had already been arrested and charged with rape and murder.

"Help me out with this a little bit, Damon, because I can't imagine in my wildest dreams admitting to a horrific crime, including giving some grizzly details if I didn't do it," said Moriarty.

"At first I thought so, too. But ... after not sleeping, not eating ... I'm thinkin', 'Well, OK. I'll give 'em what they wanna hear and the evidence'll come out and it'll show I didn't do it and people will see that," he explained.

In fact almost nothing Damon Thibodeaux said matched the evidence, says LeBoeuf.

"They could've known within 24 hours that the confession was really stinky, that it almost couldn't be true," she said.

At first glance, it did appear that Crystal had been raped.

"Her shorts and her underpants were down about her knees," said Dr. Fraser Mackenzie, the state pathologist.

But when Dr. Mackenzie conducted the autopsy, he found no sign of sexual assault.

"She didn't have those kind of injuries?" Moriarty asked.

"No," Mackenzie replied. Nor did he find any seminal fluid.

Thibodeaux also told investigators that he choked Crystal with his hands. Not likely, says Mackenzie.

"There's no kind of injury that would be associated with using your hands?" Moriarty asked.

"Correct," Mackenzie replied.

Instead, the neck injury was caused by red industrial wire. Police found its source hanging on a nearby tree.

"They ask him, 'Where'd you get the wire?' And he said, 'From the trunk of my car,'" LeBoeuf said. "They say, 'What color is the wire?' And he said, 'It was clear, like speaker wire.'"

Officer: Could it have been another color ...

Damon Thibodeaux: I've got black wires and gray wires in my car also.

Officer: How about red wires?

"And when the interrogator finally says, 'Did you have any red wire?' Come on," LeBoeuf commented.

Officer: You wrapped the wire around her neck twice?

Damon Thibodeaux: Yes.

"We did believe that we had the right guy. We did believe that it was -- a good case. And we believed that he was the... the perpetrator," said Paul Connick, who became the Jefferson Parish District Attorney six months after the murder.

"It's hard to believe that anyone would confess to such a -- terrible crime -- if they didn't commit it," he said.

When Damon Thibodeaux went on trial in 1997, he was confident that facts would show that he had falsely confessed.

"I'm thinkin', well ... this is all gonna come out in the courtroom and -- this jury's gonna see, well, this guy didn't do this and -- that'll be the end of it," said Thibodeaux.

There was no physical evidence tying him to the crime.

"They had 84 pieces of physical evidence in this case. And not one went back to Damon Thibodeaux," said LeBoeuf.

But a detective explained the lack of evidence of rape by suggesting that insects had consumed all the fluids -- a theory that he never discussed with the state pathologist.

"You're actually laughing. Is his explanation laughable?" Moriarty asked Mackenzie.

"In my opinion. But I'm knowledgeable. For a jury, they're not knowledgeable," he replied.

"But could that have destroyed any evidence of sexual assault?" Moriarty asked.

"No. No," Mackenzie replied.

The jurors also heard from two women who claimed seeing someone who looked like Thibodeaux on the levee the day of the murder. Damon did not take the stand, so he did not explain why he admitted to the crime before recanting. His incriminating words echoed in the courtroom:

Officer: But everything you said here is true and to the best of your knowledge?

Damon Thibodeaux: Yes.

"What went through your mind as you're listening to these?" Moriarty asked Thibodeaux.

"Why couldn't I be a little stronger," he replied.

Getting Help

Asked what it was like seeing Damon Thibodeaux in the courtroom, Dawn Champagne said, "It hurt. I just wanted to ask him, 'Why?'"

Champagne was convinced that Thibodeaux killed her daughter.

"These are people you consider family, and they think you killed Crystal. What was that like?" Moriarty asked Thibodeaux.

"It was weird. I mean what, what -- what do you tell someone in a situation like that?" he replied.

Jurors took just one hour to reach their verdict.

"You get the sinking feeling that this isn't gonna go right -- and then here it comes," said Thibodeaux.

Asked what he remembered hearing, he told Moriarty, "Guilty."

Guilty. Thibodeaux was convicted of the rape and murder of Crystal Champagne.

"I was glad -- because it meant that they had who did it," said Dawn Champagne.

His sentence: death by lethal injection. In October 1997, Damon Thibodeaux was sent to Louisiana's notorious Angola prison. He began to despair.

"You get to a point where you don't wanna be in that cell anymore and that's the only way out," Thibodeaux said.

"Execution?" Moriarty asked Thibodeaux.

"That's the only way out of that cell," he replied.

"What made you change your mind then?"

"Denny," he replied.

Denny, as in Denny LeBoeuf.

"She walks in one day," Thibodeaux said. "She said, 'Look, I read your case.'"

LeBoeuf's an anti-death penalty attorney, now working for the ACLU, who fights to get inmates off of death row - no matter what they did to get there.

"I mean, you make no bones about it. Most of your clients are guilty," Moriarty noted to LeBoeuf.

"Absolutely," she replied. "And the work that I do, I wanna do on behalf of people who have, tragically, committed a homicide. That ain't Damon."

LeBoeuf was convinced that Damon Thibodeaux was innocent. She immediately appealed the verdict. But two years after Damon stood trial, the State Supreme Court reaffirmed his conviction -- a major victory for Jefferson Parish District Attorney Paul Connick.

"You still feel it's a good verdict?" Moriarty asked Connick.

"Oh, absolutely," he replied. "We had the confession. ...We had two witnesses who put him on the scene of the murder around the time of the murder."

Denny LeBoeuf couldn't give up, but she was overwhelmed. She sought help and found it in a place 1,200 miles away in Minneapolis.

Steve Kaplan was a partner at Fredrikson & Byron, a well-heeled civil law firm that takes on a few select criminal cases pro bono.

"As soon as I met him ... It completely changed the stakes for me. It was not clinical. ... It was deeply personal," Kaplan explained. "It was ... the look he gave me as -- as he was saying goodbye. That I remember. Will always remember."

"His life is in your hands?" Moriarty asked.

"Correct," Kaplan replied.

"How big a difference did it make when you got help from Minneapolis?" Moriarty asked LeBoeuf as they stood by the levee.

"Everything," she replied.

Right away, the attorneys took another look at the witnesses who said they saw a man who looked like Thibodeaux on the levee.

"But they then said, 'And you know, the police tape was around, and the police were here.' Well, that was the night they found her, not the night she was killed," LeBoeuf pointed out.

They also reached out to the now-retired state pathologist Dr. Fraser Mackenzie. When he testified at the trial, he didn't know the details of the case.

"All I know was there was a confession. I have no knowledge whatsoever of what is contained in that confession, none," said Mackenzie.

"And when you find out?" Moriarty asked.

"Then I'm really upset," he replied. "The confession does not match the physical evidence."

"When you heard that he was convicted of rape what did you think?" Moriarty asked Mackenzie.

"I was just aghast. Because at my examination there was no evidence of a rape," he replied.

Mackenzie signed an affidavit for the defense, outlining the serious discrepancies he found in Thibodeaux' story.

"I want the truth to come out and -- and for it to be known," said Mackenzie.

What's more, Mackenzie was able to help establish the time of Crystal's death -- sometime before darkness fell at 7:50 p.m. -- about two and a half hours after she left her home. That's crucial, because Damon Thibodeaux was with Crystal's family for most of that time.

"There was absolutely no time within which Thibodeaux could've possibly committed the crime," said Kaplan.

The defense contends that Thibodeaux was only on his own for about a half hour to 45 minutes.

"I sat in the parking lot in my car," said Thibodeaux.

Asked how long was he gone, he told Moriarty, "Just long enough to smoke a joint."

"It's 10 minutes from the apartment to the crime scene. Another 10 to come back. That's 20 minutes, Kaplan explained. "And it ... would've left no time for him to have done the murder ... cleaned up, disposed of all the incriminating evidence, cleaned his car, and gotten back to the Champagne's, presumably fully composed and ready to rejoin the search."

"Was there anything about Damon that made him more likely to be manipulated?" Moriarty asked Kaplan.

"I think so," he replied. "He was only 22. He had never been through anything like this in his life."

And his background made him even more vulnerable, Kaplan says.

"I'm not asking for specifics, but you were abused as a child, weren't you?" Moriarty asked Thibodeaux.

"Yeah. Yeah," he replied.

"Dropped out of school," Moriarty continued.

"Yes," Thibodeaux replied.

"Damon had ... a childhood that was very, very tough, and that produced a guy who would just rather walk away from a fight," said LeBoeuf.

After spending nearly a decade in the most hopeless place there is, by 2005, Thibodeaux had dozens of legal professionals -- all volunteers -- fighting to get his case heard and overturned.

"I said, 'Well, if these people are gonna fight to prove I didn't do this, I'm gonna fight with 'em," said Thibodeaux.

Also on his side: attorney Barry Scheck and the Innocence Project based in New York.

"Well, this was a no-brainer for us," Scheck told "48 Hours". "You could see that this confession was quite problematic from the start."

Scheck says that while 25 percent of the country's exonerated inmates had confessed to crimes they didn't commit, the hard fact is no court is likely to release a man who admitted to such a brutal murder. So he came up with a novel and controversial idea. Instead of fighting lengthy court battles that were iffy at best, why not take Thibodeaux's case directly to their adversary?

"We believed," Scheck explained, "that we could persuade the Jefferson County District Attorney's Office that they were dealing with an innocent man."

But that would mean showing the D.A. everything they had.

"There's always the danger that ... all of the sudden you'll come up with some horrible evidence of guilt. That can happen," said Scheck.

"If you don't get Damon out, he's gonna die," Moriarty noted to LeBoeuf.

"I have been in the death houses at night when they kill my client. And watched that. And I know how real it is," she replied.

Re-examining the Evidence

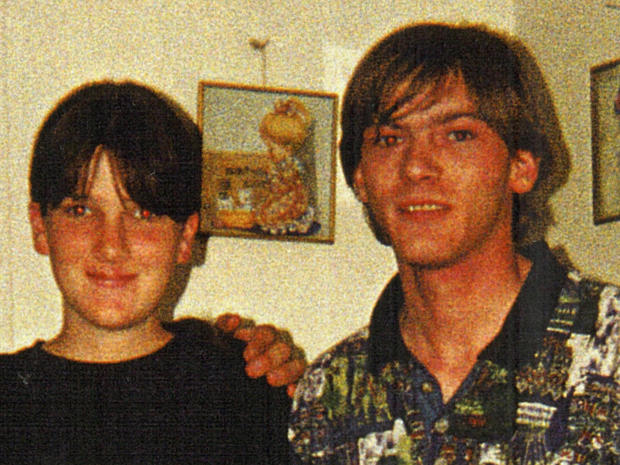

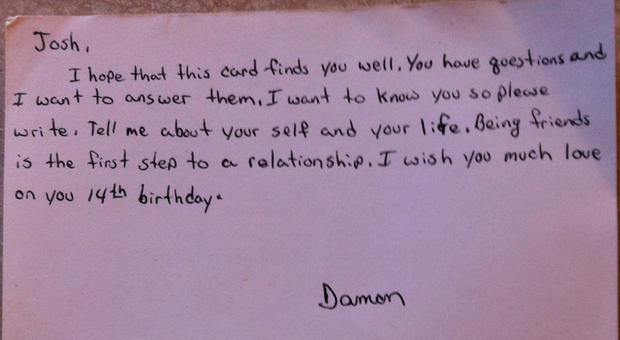

In the rural town of Hanceville, Alabama -- 450 miles away from Angola prison -- a 14-year-old boy got a shocking letter from a death row inmate. It was a birthday card from the father he had never known.

"I was like, 'What -- who is this?" said Josh.

"I hope this card finds you well. You have questions and I want to answer them. I want to know you so please write..."

The letter was signed "Damon".

"Not 'Dad?'" Moriarty asked Thibodeaux.

"I didn't think I earned the title 'Dad', you know, because I was never there," he replied.

Damon Thibodeaux was 17 when his son, Josh, was born. Thibodeaux lost contact with him when he broke up with Josh's mom.

"I wanted to be part of his life, but," Thibodeaux explained, "I was -- I was a stranger to him."

"I wrote him back and -- and pretty much asked him who he was," said Josh.

"I wanted Josh to know that I wasn't a murderer," Thibodeaux told Moriarty.

"At that time, I didn't know if he was guilty of it or not," said Josh.

After many letters over several years, Josh began to believe in his father.

"I wanted to meet him," Josh explained. "I wanted to meet my dad. ...And he didn't want me to do that."

"Did I want to see him? Yes. Very badly. But I wanted to be able to talk to him without having chains on my feet. Hug him without having chains on my feet," said Thibodeaux.

But fighting a case post-conviction takes lots of time. So in May 2007, having already spent nearly 10 long years on death row, Thibodeaux agreed to allow Barry Scheck and his other lawyers to show the district attorney all the evidence they had gathered.

"There was some skepticism," Scheck said with a laugh. "The -- man is on death row. He's on death row! ... It's a horrible murder."

Surprisingly, Jefferson Parish District Attorney Paul Connick was willing to hear them out.

"He came in ... along with his team. ... I had all of my chiefs in the room," Connick said. "The ... easy thing to do would be rely on the conviction, you know. This is -- can be politically a hot potato here, why are we gonna reopen this case? Let's just leave this lie and let the courts decide."

"I bet there are people in your office who said that," Moriarty noted.

"They're thinkin, 'Hey. This is good conviction. Why -- why are we goin' down this road?" Connick said. "But certainly there was enough presented to me, where as I sat there I'm thinking, 'I gotta look at this.'"

Connick was troubled enough by what he saw that he agreed to open an investigation - not just working along side the defense team, but also splitting costs. They would re-examine the physical evidence.

"This was a bloody crime scene and a bloody struggle," Scheck said. "There would have to be ... some transfer of trace evidence on the person who committed this crime."

"I said let's take another look at what was already tested, using today's technology," said Connick.

The risks haunted Denny LeBoeuf, who feared Thibodeaux's DNA could have innocently ended up on Crystal.

"This is a very scary thing," she said. "They're gonna test his clothing and his car for hairs. And she lived in the house where he ... slept on the sofa. ... She'd ridden in his car.

"It would stop this case cold, I believe, if one little bit of forensic evidence matched Damon," LeBoeuf continued.

But there was little choice. Every bit of the clothing that Thibodeaux and Crystal had worn was scrutinized for any speck of tell-tale DNA. In all, the testing took another two years.

"Was ... any DNA -- from Damon Thibodeaux found on any of the evidence?" Moriarty asked Connick.

"No. No," he replied.

"Was anything from Crystal found on anything belonging to Damon Thibodeaux?"

"No," said Connick.

"Was there anything that connected Damon Thibodeaux to the crime scene?" Moriarty pressed.

"No," Connick replied.

"I was expecting those results," said Thibodeaux.

"But you had to be thrilled?" said Moriarty.

"Oh, yeah. Definitely I was thrilled. 'Cause now I had something tangible to stick in front of the D.A. and say, 'Look, you got the wrong guy,'" he replied.

But Connick saw other problems with the case, like the defense claim that Thibodeaux didn't have enough time to kill Crystal. Was that true? It all hinged on Crystal's mother, Dawn Champagne. She first told police Thibodeaux was back at her home when she called 911.

But later at trial, she said he wasn't.

"When we questioned her about her trial testimony, she went back and forth and finally said, 'Whatever I told the police is my best recollection,'" said Connick.

If that's right, and Thibodeaux was with the family by then, it was virtually impossible for him to have driven Crystal to Bridge City. Yet, since he confessed so soon after Crystal's body was found, police never looked into who else might have taken her there.

"There was never a wide-ranging investigation, as there should've been after a homicide," said LeBoeuf.

Denny LeBoeuf says there were plenty of people to question, like the friend who said he spoke with Crystal on the phone just hours before she disappeared, or the relative with an arrest record for violent crimes who lived close to where her body was found. And Crystal did have friends in Bridge City, including one now serving life for aggravated rape of a juvenile.

"I can't tell you if any one of those men did the murder, or -- or knows anything about the murder. I can't tell you sitting here. What I can tell you is that any decent investigation would've asked them," said LeBoeuf.

And what about that family friend who found Crystal's body hidden deeply in the brush along the Mississippi River?

Police call: Some people come walked over here a minute ago and they found a little girl dead by the river.

Just how did he manage to do that?

"What made you go look [at] that one other spot?" Moriarty asked John Tomlinson.

"Because of the dream. That's all I can say, because of the dream," he replied.

The Dream

"You have to look at the case and say, 'Let's start with the oddities, the things that really don't add up," said private investigator Jen Vitry, who was part of Damon Thibodeaux's post-conviction defense team and is a CBS News consultant.

And what really doesn't add up, says Vitry, is how and where 14-year-old Crystal Champagne was found.

"This is the Huey P. Long Bridge," Vitry told Moriarty as they stood at the levee. "And at the foot of the bridge here comes into a community called Bridge City."

Crystal's body was discovered deep in the brush, around five miles from where the teenager had disappeared alone on foot.

"Everybody in the entire police department is looking for her in Westwego, which is 15 minutes away," said Vitry.

So how did John Tomlinson happen to find her in the very first place he looked?

"It's somethin' about me. See there's weird things that people don't understand about me. I can have a dream. And it'll actually come true. And it scares me," he explained.

A dream, Tomlinson claims, led him to the body; although in 1996, he told police it was his "intuition."

"What did you actually dream?" Moriarty asked Tomlinson.

"All's I -- in my dream -- was remember just starin' up, and bein' standing right underneath the Huey P. Long Bridge," he replied.

"48 Hours" tracked down Tomlinson to Ball, Louisiana, where he was working as an auto mechanic. Back in 1996, he was a 30-year-old tugboat deckhand living in the same Westwego apartment complex as Crystal's family.

"It -- it haunts me every day that I found her body," Tomlinson said, choking up. "It kills me every day."

"What do you mean? Tell me," Moriarty asked.

"She's a good kid. She didn't deserve," an emotional Tomlinson replied, "she had a lotta life to go."

Tomlinson had been dating Stacey Melancon, a close friend of Crystal's mom. Crystal often babysat for Melancon and was at her home just hours before she disappeared. Tomlinson insists he was on a tugboat - asleep -- when Melancon called to tell him that Crystal was missing.

"It never really run my mind that she would run away. I mean, she was too good of a kid. She was too happy," he said.

The next evening, Tomlinson says, Melancon picked him up at the dock and they handed out flyers in neighboring Bridge City - even though they were far from Crystal's home. At a convenience store, he says, a woman told them she had seen a girl who looked like Crystal walking alone on the levee, about a mile from the bridge.

"So I said, 'OK, Stacey, let's go take a little trip,'" said Tomlinson.

But Tomlinson didn't search the area where Crystal was reportedly seen. Instead, he drove on for about a mile, stopped the car, and told Melancon to stay behind.

"That dream is what drug me there," Tomlinson explained.

Then, without hesitation he says, he followed a path into the woods.

"There's a little trail here, you know," Tomlinson explained. "And I walked in. And God's love there she was."

"Where was she?" Moriarty asked.

"Dead under the Huey P. Long Bridge. When I looked up I was lookin' at the same thing that I was lookin' at in my dream that I -- when I was standing on the tugboat," he replied.

"How did you know that that's where you would find Crystal's body?" Moriarty asked.

"A hunch. Just a hunch -- based on the dream, just a hunch," Tomlinson replied.

That story obviously didn't go down well with investigators, who took Tomlinson in for questioning:

John Tomlinson: And I walked in about ten feet and found the body.

Officer: What made you go there?

John Tomlinson: Intuition.

"I went through nine-and-a-half hours of intense interrogation," Tomlinson said. "'Cause it was the same thing over, and over and over. ... I really felt like they were tryin' to make me say that I did it."

That is until Damon Thibodeaux, going through his own interrogation down the hall, told police that he did it. Police then lost interest in Tomlinson, especially since his alibi, claiming that he was on a tugboat that was far downriver on the night Crystal was killed, appeared to be backed up by the boat's logs.

"I proved while I was on that boat that there's no way that I could do it," said Tomlinson.

But how airtight was that alibi? Tomlinson concedes that crew members covered for each other all the time.

"Now, at the time though, you told them it was impossible to get off the boat and it wasn't, was it," Moriarty pointed out to Tomlinson.

"Well, sure, you know, I mean, no, it's not. It never is, you know. But I always let my boss know when I was gettin' off that boat," he said.

"But you could get off and nobody --"

"Sure," Tomlinson interrupted.

"-- would have to know," Moriarty continued.

"Sure," he agreed.

"And you could get right back on?"

"Sure. You can get off and get right back on. It's no problem, you know. I mean, it's a boat," Tomlinson reasoned.

"But some nights you would sneak off there and go see Stacey?" Moriarty asked.

"Sure," he replied, nodding his head in agreement.

"When you were -- supposed to be sleeping in the bed?"

"Sure," he said. "And I was sleepin' at home (laughs)."

"You didn't meet up with Stacey on that Friday night -"

"No, no," said Tomlinson.

What's more troubling is that Tomlinson was convicted of a sex offense two years before Crystal disappeared. His crime: indecent behavior with a juvenile.

Here's how he explains it: "I had picked up a 14-year-old girl -- thought she was 18 at least -- at a bar. And got in trouble for it. Paid my dues and done my time," he explained.

"And you never were inappropriate with Crystal -" Moriarty asked.

"No, never," Tomlinson replied. "That's the wrong thing. You know, I was raised the right way. ...You'd never try to hurt a child."

Crystal was also 14, but Tomlinson denies having anything to do with her murder.

"You had nothing to do with her death?" Moriarty asked.

"On my mother's soul I never touched her," Tomlinson replied.

He blames the crime on the man who once said he did it: Damon Thibodeaux.

"He admitted to what he did wrong. He should be punished," said Tomlinson.

That confession is, no doubt, the biggest obstacle to Thibodeaux's freedom -- especially for the man who agreed to take a new look at the case, District Attorney Paul Connick.

"After all was said and done," Moriarty said to Connick, "you still had this thing, like, 'Why would somebody confess?'"

"Why?" Connick replied. "I'm not gonna take the boilerplate explanation for false confessions."

Connick was skeptical that the interrogation tactics were to blame, so he turned to Dr. Michael Welner, a tough forensic psychiatrist who often sides with the police.

"I don't believe there exists evidence of any false confession in which a person confessed falsely to murder because he didn't get a meal," said Welner.

"I needed to know, can I rely on this confession? 'Cause that's all I have," said Connick.

"False confessions are extremely rare," said Welner.

"I trust him. I trust him. I really do," said Connick.

"Dr. Welner insisted on talking to Damon Thibodeaux by himself," Moriarty commented to Connick.

"Yes," he replied.

"No lawyer present," said Moriarty.

"Yeah, yes, yes," Connick replied.

"That had to drive the defense crazy," Moriarty noted.

"And we knew it," said Connick.

With his life riding on this interview, Damon Thibodeaux agreed to meet with Dr. Welner alone.

"I was afraid that he would ... paint Damon as a different person than he is," said LeBoeuf.

Asked if Thibodeaux was the person he was expecting to meet, Welner told Moriarty, "From the background that was presented to me ... I anticipated meeting somebody who would've been crushed, crumpled and spit out.

"The person that I met was composed. Self-possessed," Welner continued. "I was shocked."

"What was going through my mind is, 'Did we make a big mistake?'" said LeBoeuf.

An Extraordinary Decision

"Was Damon Thibodeaux coerced by the police into giving a false confession?" Moriarty asked forensic psychiatrist Dr. Michael Welner.

"In my professional opinion, he was not." He replied.

Welner does not believe that Thibodeaux was forced into confessing, but he does believe that if Thibodeaux had committed the crime there would be some physical evidence.

"It was a bloody event. It was a physical event ... that required restraint. That required contact," said Welner.

Still, Welner says that Thibodeaux did blame himself, believing that if he had given Crystal a ride to the store on that fateful afternoon, she might still be alive.

On top of that guilt was Thibodeaux's failed polygraph.

"To some people, failing a polygraph is powerful evidence," Welner said. "You might be better off confessing."

What's more, he says, guilty suspects try to minimize their involvement in crimes. Thibodeaux was admitting to a rape that didn't happen.

"As you sit here today, do you believe that Damon Thibodeaux falsely confessed?" Moriarty asked Welner.

"I do," he replied."There are many things about this case that I can't answer, but one thing that I can say is that I believe this to be a false confession."

And now, so does the man who once put Damon Thibodeaux on death row.

"We relied too much on the confession in the beginning, when we should've ... gone further," said District Attorney Paul Connick.

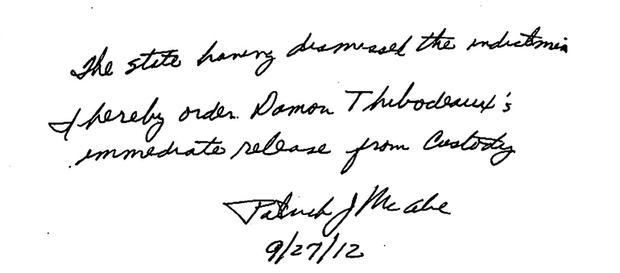

Five years after that first meeting with Thibodeaux's team, Connick makes an extraordinary decision: he will not fight Damon's bid for freedom.

"There's no way I can ... keep this man in jail. There's no way," he said.

The defense and Connick file a joint motion in court. That same day, a judge orders the conviction vacated -- adding in a handwritten note that Thibodeaux should be immediately released.

In September 2012, 16 years after Thibodeaux's arrest, his legal team gathers anxiously at the gates of Angola.

"Denny, have you ever come here and watched someone walk out of here? Is this the first time?" Moriarty asked LeBeouf.

"This is the first time. Ever," she replied.

"That you've ever watched someone walk out alive. Out of Angola," Moriarty noted.

"Yes. It is. The first time," LeBoeuf replied.

After walking out of prison, Damon Thibodeaux is asked by a reporter how it feels to be free.

He then shares an embrace with LeBeouf before getting into the car with Kaplan and leaving.

"Yes, I am in the car -- driving away from the gate," Thibodeaux tells Barry Scheck over the phone. "Starting to feel free! (laughs)"

Five hours later, Thibodeaux is in New Orleans reunited with his family. His son, Josh, finally gets to meet his father in person.

"When you first saw him come off that elevator, when you realized that was your son ... what were you feeling?" Moriarty asked Thibodeaux.

"Relief. I finally got to meet him," he replied. "It's - indescribable."

They spend three days trying to catch up on all the lost years.

"We walked... We talked," Thibodeaux said. "We got to know each other a little better."

"So what do you think of your son?" Moriarty asked.

"I'm proud. I mean he's -- he's a great guy. He's a good man. You know? And -- I'm glad that I'm alive to see it."

"I think one of the great things of this is the opportunity now for father and son to-- to have-- a real relationship with each other. That's just unbelievably special," said attorney Steve Kaplan.

Kaplan's commitment to Thibodeaux isn't over yet. Damon is moving in with him until he gets settled. They embark on the 1,200-mile journey to Minneapolis:

"And I get to sit in the front seat!" Thibodeaux said to Kaplan with a laugh as they drove.

"There you go. No chains," Kaplan quipped.

"No chains. I'm not in the back seat. And I don't have bars on the windows," Thibodeaux said during the trip. "I'm shaking the chains off. And I'm starting over."

"This is a man that your office convicted -- put on death row and then 15 ... years later, to turn around and say, 'I'm gonna let him go,' wasn't that a very tough decision?" Moriarty asked Connick.

"The process was tough. But in the end, it's what should've been done," he replied. "In my heart I knew what I did was the right decision."

"The fact that so much time now has passed, to start taking a new look at this case, isn't it going to make it very difficult to find the real killer?" Moriarty asked.

"It is. Again, what's the alternative? We can't -- we can't stop. That's what we do. It's our job," said Connick.

The murder of Crystal Champagne is now an open case, so Connick cannot talk about specifics, but the state is actively reinvestigating. That's sure to mean taking a fresh look at several people, including John Tomlinson.

Dawn Champagne can only hope that the renewed investigation will pay off.

"There's a lot of things I don't understand, a lot of things I don't know," she said.

All she wants is justice for her daughter who went out to a store and never made it home.

"Because whoever did it, they walkin' free. And she didn't have a chance to live," said Champagne.

After Thibodeaux was released he earned his GED. He now works for a commercial trucking company.

Thibodeaux was invited to testify before Congress about conditions on death row.

He is now a grandfather.

HAVE INFORMATION ABOUT THE CRYSTAL CHAMPAGNE CASE?

Anyone with information is asked to contact the Jefferson Parish District Attorney's Office tip line at (504) 361-2764 or by e-mail: tips@jpda.us