Curiosity's Mars travel plans tentatively mapped

(CBS News) The Curiosity rover likely will spend the rest of the year monitoring the Martian weather, collecting radiation data and analyzing rock and soil samples near its landing site in Gale Crater. Only then will it head for its ultimate target, the rugged foothills of Mount Sharp just four-and-a-half miles -- but many months -- away, the project scientist said Friday.

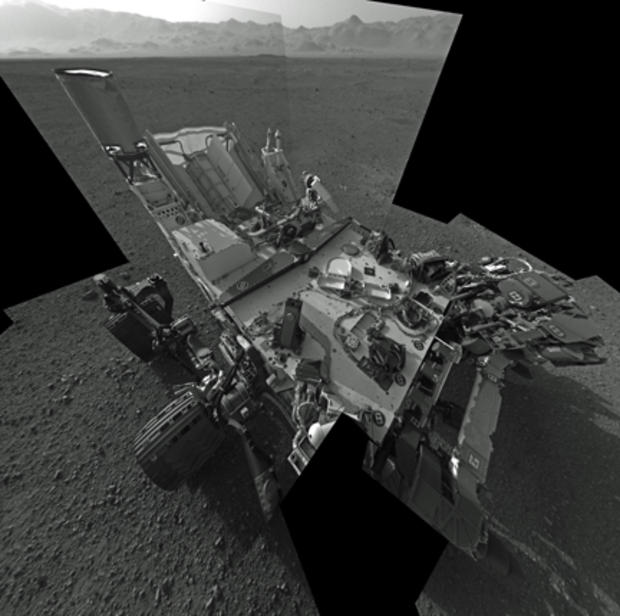

John Grotzinger told reporters the nuclear-powered rover continues to sail through its initial test and checkout phase with no major problems or anomalies. The latest successes to report include activation of a neutron generator in a Russian instrument known as DAN, for Dynamic Albedo of Neutrons, that will be used to look for traces of sub-surface water when science operations begin in earnest.

"The excitement from the point of view of the science team is all the instruments continue to check out and we're very pleased to report the DAN instrument, which is a neutron generator, was turned on today and operated successfully," Grotzinger said. "That instrument operates by executing a one-microsecond pulse and it does 10 of those per second, and it did it for 15 minutes, roughly.

"At the same time that instrument was operating, the RAD (Radiation Assessment Detector) was listening to DAN and confirmed that it was operating."

The Rover Environmental Monitoring Station, or REMS, also was collecting data about the weather on Mars, showing a high temperature Thursday of a relatively balmy 276 degrees above absolute zero, or about 37 degrees Fahrenheit.

"It's really exciting to see this data come out," Grotzinger said. "It's really an important benchmark for Mars science because it's been exactly 30 years since the last long-duration weather station was present on Mars. That was when the Viking 1 lander stopped communicating with the Earth, that was back in 1982. So 30 years later, we're happy to be on the surface doing that monitoring again."

Engineers plan to carry out initial tests of the rover's drive-and-steering systems next week, with science operations focusing on getting as much data as possible from the rocks and soil at the landing site. Of particular interest is an area where Curiosity's sky crane rockets blasted away topsoil as the rover was lowered to the surface, exposing underlying rocks to its instruments.

One of those instruments, known as ChemCam, uses a powerful laser to vaporize rock and soil samples that are then analyzed by a telescopic spectrometer. Its first target will be a rock near the rover with a smooth, flat surface,

"There's a high-power laser that briefly projects several megawatts onto basically a pinhead-size spot on the surface of Mars," said Roger Wiens, the principle investigator. "With that much power density, it creates a plasma, or a little ball of flame or spark. ... So the telescope observes this flash and we can (observe) these flashes up to about 25 feet away. The telescope then takes that light and directs it into a spectrometer."

ChemCam also features a camera capable of photographing a human hair seven feet away.

"We have basically done everything with this instrument except for turning the laser on," Wiens said. "We've checked everything out, we've tested the spectrometer, we've taken some passive spectra ... everything checks out.

"In summary, we're really excited," he said. "Our team has waited eight long years to get to this date and we're happy that everything is looking good so far. Hopefully, we'll be back early next week and be able to talk about how Curiosity's first laser shots went."

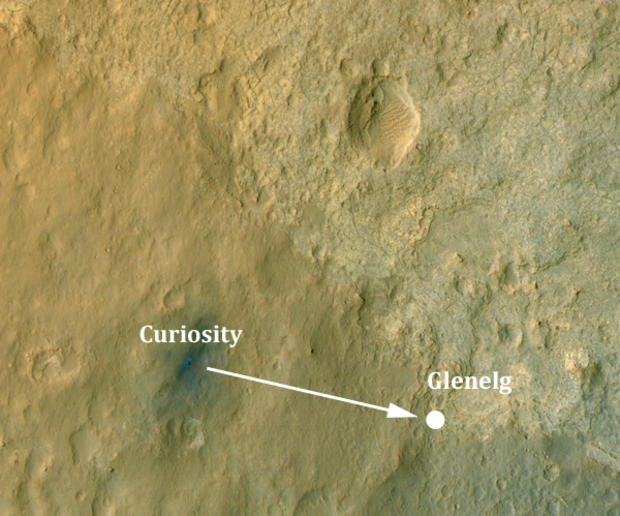

Grotzinger said Curiosity will remain at its landing site for several more weeks before eventually heading to a nearby area dubbed Glenelg, a palindrome that takes its name from a rock formation in Canada. In high-resolution views from orbit, Glenelg features three different types of geology, including denser material thought to be part of an alluvial fan where water once flowed into the crater.

On the way to Glenelg, the rover likely will stop and analyze interesting soil and rock samples and Grotzinger made it clear that Curiosity will not be in any hurry.

"If we continue down the nominal path, and we're on track to do that, it's probably going to be a couple of days, sometime next week, you should hear about what will hopefully be a successful set of tests involved with first wheel motion," he said. "Toward the end of next week, we'll probably finish up ... continued instrument checkouts.

"Then we'll roll into a period of time called 'intermission,' and the first part of that is going to be some very specific science experiments that are going to be quite thorough and that will involve the Mastcam instrument, the ChemCam instrument and also first use of SAM (Sample Analysis at Mars) to attempt to test the TLS (tunable laser spectrometer) instrument that's capable of making measuring of the composition of atmosphere. After that, assuming all is nominal, we intend to hit the road."

Grotzinger said he expects it will take a month to a month and a half to reach Glenelg, assuming no major problems and a few stops along the way.

"Probably we'll do a month worth of science there, maybe a little bit more," he said. "Sometime toward the end of the calendar year, roughly, I would guess then we would turn our sights toward the trek to Mount Sharp."

Gale Crater was chosen as Curiosity's landing site in large part because of Mount Sharp, a three-mile-high mound of layered rocks that likely captures hundreds of thousands to tens of millions of years of martian history. Curiosity will attempt to climb the lower slopes of Mount Sharp to look for signs of carbon compounds and evidence of past or present habitability.

A color photo released Friday shows the foothills of Mount Sharp in the distance, an image that clearly sparks Grotzinger's scientific curiosity with hills the size of multi-story buildings and valleys in between them 'being broad boulevards and highways."

"This is simply a thrilling image that underscores the reason we chose this landing site," he said. "That's about 7 kilometers away (4.4 miles) from where the rover is now. What's really cool about this topography is that the crater rim kind of looks like the Mojave Desert and now what you see here kind of looks like the Four Corners area of the western U.S., or maybe around Sedona, Ariz., where you've got these buttes and mesas made out of these layered, kind of light-toned reddish-colored outcrops, there's just a rich diversity over there.

"There should be hydrated minerals in all those layers. So ultimately, that's our goal. We've got stuff to do before we head there, but that's our broad, strategic plan right now."