Congrats, class of 2015, and welcome to a grim job market

The class of 2015 can't be blamed for tossing their graduation caps into the air with a great deal of trepidation.

The tepid demand for workers and weak wage growth that continues to hamper the U.S. job market is forcing many newly minted college graduates into low-paying, low-skilled jobs, according to a new report from the left-leaning think tank Economic Policy Institute. And that's for those who are lucky enough to find a full-time job, given that the ranks of recent college grads who are underemployed have continued to swell in recent years.

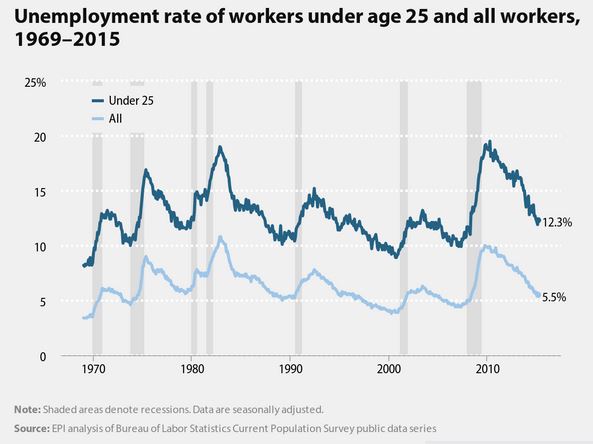

While younger people have always suffered from higher unemployment than older workers, the Great Recession has has an uncommonly long and severe impact on young workers. Even though the unemployment rate is falling, it still remains almost 2 percentage points higher for recent college grads than in 2007, before the recession started.

Young workers with only high school degrees are predictably in even worse shape, with almost 1 in 5 out of work today, compared with 15.9 percent in 2007. Wages of young workers are also substantially lower than they were in 2000, while many are leaving college with significant student debt, thanks to college costs rising much faster than family incomes.

"The class of 2015 is entering an economy that's still recovering from the Great Recession," said Elise Gould, senior economist at EPI, on a conference call to discuss the study. They are joining "six other classes of students who have graduated into a weak economy in recent years."

Given weak demand for new workers, that's increasingly pushing many recent grads into jobs that don't require college degrees, the study found. Before the recession started, about 38 percent of employed college graduates under 27 years old were working in a job that didn't require a college degree. By 2014, that had jumped to 46 percent of college grads working in such jobs.

Those jobs also tend to be of lower quality than they were before the recession, when more grads took career-oriented or higher paying jobs that didn't require college degrees, such as working as an electrician or a dental hygienist. Now, more college grads are working in low-paying jobs that don't require degrees, such as food server or bartender, the study found.

"The bottom line is that for recent college graduates, finding a good job has become much more difficult," the report noted.

While there's a widely held belief that many young workers have ridden out the recession by remaining in school, that's not really the case, EPI noted. Enrollment at U.S. colleges actually declined from 2012 to 2014 and hasn't picked up. Because students often need to work to pay for college or cover living expenses, that's making it harder for many to remain in school, given the weak labor market.

At the same time, their parents may be still struggling themselves to regain their financial footing after the recession, and may not be able to help cover the cost of college.

Earning a college degree is increasingly expensive, with the rise in costs far outpacing the growth in household income. The cost of a four-year degree increased almost 126 percent in the 2013-14 enrollment year, compared with 1983-84, EPI said. Median family income, however, only rose 16.8 percent during that time.

So with fewer young Americans able to afford college and with more unable to find good jobs, there's an increasing segment of 20-something workers who are "idled." That means they're neither working nor enrolled in school, EPI noted. In 2007, about 14 percent of young high school graduates were idled, but that had jumped to 17.7 percent in 2014.

Young black and Hispanic students are more likely to be left idled, the study found. "That means that nearly a quarter of young black high school graduates and nearly a fifth of young Hispanic high school graduates are not on the two major paths to future career success," the study noted.

Even for those who have managed to find a full-time job, wages are far below where they were for the recession. In inflation-adjusted dollars, the pay for young high school grads is 4.8 percent below 2007 levels, while wages for recent college grads have dropped 2 percent. That will likely have a long-term impact on today's recent graduates, said EPI research assistant Will Kimball.

"Earnings may be impacted for 10 to 15 years afterwards," he said. "Because the class of 2015 has unlucky timing -- through no fault of their own -- they are likely to fare poorly for at least the next decade."