Common Core: What's right for special education students?

NEW YORK - Nothing lights up 10 year-old Billy Flood's face brighter than when you talk to him about music. The pint-size Beatles fan loves writing his own songs, and playing the keyboard and bass. However, when getting on the topic of Common Core and end-of-the-year testing that light dims a little.

"It was kind of a nerve-wracking experience," said Billy, a fifth-grader at a public school in Brooklyn, New York. "I think I was pretty nervous taking the test."

Billy, who is on the autism spectrum, is one of more than 180,000 special education students in New York state learning the Common Core state standards and who took the state test at the end of last year.

More than 40 states have implemented the Common Core State Standards Initiative setting specific achievement targets in math and English language arts.

Since Common Core was launched in 2009 - New York adopted it in 2010 - there has been a divisive national debate on these standards.

Within that debate, there are also questions as to whether special education students should be measured by the same standards and taking the same tests as general education students.

"He's come home saying things like 'I don't know anything. I can't do anything.' This is based on the two prior years of him taking the test - third and fourth grade," said Lynda Flood, Billy's mother. "It rips my heart out because I know how smart he is; I know how intelligent he is; I know what he can do. Those tests, they don't prove at all what my child is capable of doing."

Special education students in the United States have what is called an Individualized Education Program (IEP). It provides support and services for each student depending on their learning needs. Some of that support comes in the form of accommodations during test-taking like getting extra time, having some questions read out loud (depending on the test), and being in a different testing location.

However, even with these accommodations, special education teacher Julie Cavanagh doesn't think that's enough with regard to the Common Core. She firmly believes that the new standards have made learning more difficult across the board, especially for special educations students.

Cavanagh, who teaches third and fifth grade at PS 15 Patrick F. Daly in Red Hook, Brooklyn, said the new standards represent a "developmentally inappropriate curriculum" for special education students and has had the additional effect of "taking away from schools' and educators' ability to really focus on differentiated and individualized sort of goals for those students."

Cavanagh specifically teaches students who take alternate assessments, which means they don't take the same standardized tests as everyone else. These special education students also have IEPs but might receive more accommodations and modifications than other special education students because their learning disabilities are more significant.

Alternate assessment allows Cavanagh to write her own version of the end-of-the year state tests - still based on the Common Core, but modified for her students.

However, some special education teachers think the basic accommodations for their students - the IEPs - are enough to help them succeed within the Common Core framework.

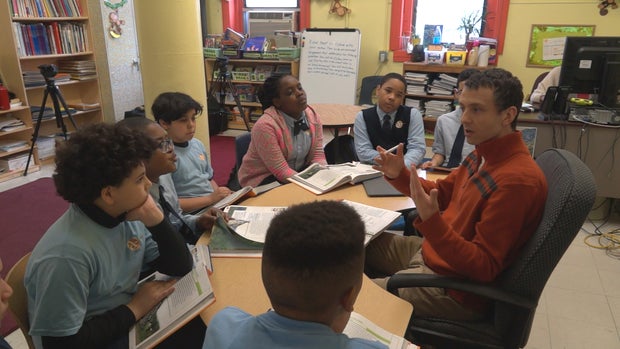

"I believe that given the opportunity, special education or not, the standards should be set high because once we're out of school, the standard is set high. So there is no real benefit for the child to set the standard low in their early life so that when they get out of school they are now not functioning as well as they could have," said Dan Blackburn, who teaches special education for kindergarten through fifth grade at Amber Charter School in Manhattan.

Blackburn's school doesn't have alternate assessment and students have to take the standardized test at the end of the year. He agrees with raising the standards and having them applied consistently across the United States. While Blackburn acknowledges there are some difficulties that come with Common Core, he believes "with the right persistence and the right attitude that it's going to help our students learn to be productive global thinkers."

Imelda Vazquez's daughter Crystal is in Blackburn's fifth-grade class. Crystal has a learning disability and English isn't her first language, but Vazquez said she is happy her daughter is held to the same high standards as the general education students.

"If she leaves [graduates] without being well prepared, it won't serve her. So it [Common Core] has to be helping her a lot," said Vazquez.

Even Cavanagh agrees there shouldn't be a two-tiered system where children who have IEP's are working toward one set of standards and children who don't have IEP's are working toward another, but feels the Common Core's "over-emphasis" on testing "really undermines the work of that individualized, differentiated experience" that has become the hallmark of special education.

Cavanagh also says the focus on teacher accountability can be counterproductive. In New York, 20 percent of an educator's evaluation is based on students' standardized test scores. Cavanagh said this puts an immense amount of pressure on the teachers as well as the students.

"I think where we run into a problem is expecting that children with or without an IEP are going to be able to demonstrate proficiency on those skills at the exact moment that the state or some [policymaker] has decided that they should be doing that."

This year, Billy's mother, Lynda, has decided her son won't take the state test, though schools with less than a 95 percent participation rate in the assessments risk losing "significant federal funding," according New York State Board of Regents Chancellor Merryl Tisch.

As for Billy, he's just trying to stay positive.

"My mom always tries to push me into confidence, no negativity. ... It works actually. ... The confidence works."