Scientists baffled by new picures of Comet ISON

After a multimillion-year plunge from the frozen fringes of the solar system, Comet ISON may have broken apart and evaporated in the fierce heat and crushing gravity of the sun before or during a close flyby Thursday, presumably scotching long-held hopes for a dramatic sky show on Earth over the next few weeks.

Or maybe not.

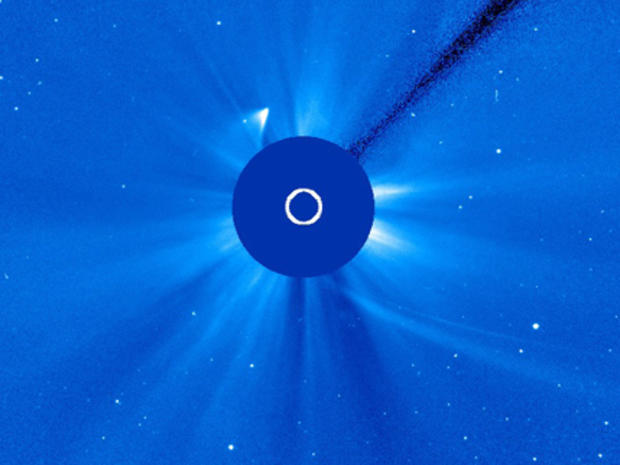

Well after many casual observers had given up on the comet's survival, updated pictures from the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory spacecraft -- SOHO -- showed what appeared to be a long trail of dust extending away from the sun along ISON's trajectory, brightening sharply toward its tip.

Whether it was just a dust trail, or perhaps dust and larger fragments of ISON -- or both -- was not immediately clear. As several observers tweeted and re-tweeted: "It is now clear that Comet #ISON either survived or did not survive, or... maybe both. Hope that clarifies things."

Matthew Knight, an astronomer at the Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Ariz., said in a telephone interview that it wasn't clear exactly what SOHO was observing.

"Initially when something came out (after close approach), we thought this is just the dust trail and there's not much left, it's just going to fade away," he said. "And then images keep coming in and ... the last few, it seems pretty definitely like it's getting brighter. So we do not have a good answer as to what's going on.

"My best guess right now, and it's really only an educated guess, is that there is something left, probably smaller fragments, because it still doesn't look like there's a nuclear condensation. Inbound, the leading edge was brighter. It doesn't look like that. It just looks to me like there are some smaller fragments that may just actually be disintegrating. They just took longer to do it."

But it's also possible, he said, there could be "still a substantial nucleus

there and it's actually outgassing. ... But I don't have any explanation for it

if there's just nothing left."

Monitored by a fleet of space telescopes, ISON, an ancient

remnant of the solar system's birth, made its close approach to the sun just

after 1:25 p.m. EST,

streaking by at more than 200 miles per second at an altitude of less than a

million miles -- an exceedingly close shave by astronomical standards.

Astronomers around the world were on the edges of their seats as the comet approached the sun, many of them convinced the three-quarter-mile-wide snowball would break up due to the blistering heat of the encounter and the tidal stresses imposed by the sun's gravitational grip.

The comet appeared to fade and smear out as it closed in on the sun and

astronomers monitoring instruments aboard two sun-watching spacecraft reported

they were unable to immediately spot any traces of ISON after perihelion, its

point of closest approach.

"In the case of Comet ISON, it appears to have disappeared and broken up into small enough chunks that over the course of hours, or a day or so, that those chunks have all evaporated," said Dean Pesnell, project scientist with NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory spacecraft.

"And once it gets small enough and sees the sun's magnetic field ... (the

fragments) don't stay together and we don't get to see them."

Karl Battams, a comet scientist with the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory,

agreed, saying ISON "probably hasn't survived this journey."

Studying an image from a coronagraph aboard the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory spacecraft, Battams said he saw no sign of ISON emerging from behind the instrument's occulting disk, used to block out the glare of the sun, "and that, I think, could be the nail in the coffin."

Asked whether the comet might still make an appearance in Earth's sky as the presumed remnants move back out into deep space over the next few weeks, Pesnell said "probably not," adding that "if we don't see it coming out from behind ... the chances of it being bright enough as it moves away from the sun are fairly small."

Later in the day, spacecraft images showed what appeared to be a trail of dusty

debris along the comet's path, but there was no sign of a nucleus or any large

fragments.

"It looks like it disappeared completely," Pesnell said in a telephone interview. "You see some dust continuing around the orbit, but that could just be large dust particles that haven't yet evaporated. But there appears to be no source of dust."

Based on initial observations with the SDO spacecraft, Pesnell believes ISON must have broken up and evaporated before it reach the sun.

"If it had done that near the sun, we would have seen it," he said. "We see oxygen and pretty much every molecule has some oxygen in it. We should have seen oxygen. The fact that we didn't see it means that it must have evaporated before it got to where we could see it."

In the meantime, he added, "We do now have a conundrum -- how do we take a half-mile wide comet and turn it into nothing? Where did that go? And I think over the next couple of months we'll figure that out."

But later in the evening, updated pictures from SOHO led many to wonder if a

large fragment of ISON had managed to survive its brush with the sun. The

pictures clearly showed the dust left in the wake of the comet as it approached

the sun, and extending on beyond it to a brighter point.

Whether that was a remnant of the comet, or just a cloud of dusty debris left

in ISON's wake, was not immediately clear.

"It's been an emotional roller coaster," Knight said.

Going into the encounter, astronomers said there were three possibilities. The

most favorable, if least likely: the comet could survive the encounter in one

piece and perhaps live up to its billing as "comet of the century," developing

a long tail that would grace northern hemisphere skies over the next few weeks.

More likely, they said, the comet would fracture and break apart. In that case, there were two scenarios. In one, the fragments would remain "active" as the sun's heat boiled away ice and dusty debris, still producing a visible tail visible on Earth. Comet Lovejoy suffered a similar fate last year and still put on a dramatic show for viewers in the Southern Hemisphere.

But given how close ISON came to the sun, they said there was a good chance the

comet would break up and be completely consumed in the glare of the star,

leaving burned-out cinders -- or nothing at all -- in its wake to disappoint

comet enthusiasts around the world.

And that may be what happened Thursday

"Breaking up is hard to do. Like Icarus, #comet #ISON may have flown too

close to the sun," NASA tweeted. "We will continue to learn."

Comets are believed to be frozen relics left over from the solar system's

birth, made up of materials in the original cloud of dusty debris that came

together 4.5 billion years ago to form the sun, its retinue of planets and the

asteroids now orbiting between Mars and Jupiter.

A sphere of icy debris known as the Oort Cloud extends from the outermost

planets halfway to the nearest star. The most distant objects are barely held

by the sun's gravity and an occasional disturbance -- a passing star, for

example, or perhaps an unusual planetary alignment -- can alter orbits and

cause an object to fall into the inner solar system.

Several million years ago, long before humans ever looked up at the night sky in wonder, Comet ISON was nudged onto a different trajectory, beginning the long fall toward the sun.

Unlike some comets, which make repeated trips around the sun in long, elliptical orbits, ISON was making its first visit and thus represented a pristine sample of the original solar nebula that coalesced to form the solar system.

ISON was discovered by two Russian astronomers in September 2012, early enough to give astronomers time to plan a coordinated global observing campaign using a battery of ground- and space-based telescopes, including the Hubble Space Telescope, the Chandra X-ray Observatory, a Mars orbiter and even the MESSENGER spacecraft orbiting Mercury.

Close in to the sun, a fleet of solar observatories focused on ISON, including

the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory, or SOHO, NASA's Solar Dynamics

Observatory, and the twin STEREO spacecraft.

In a SOHO coronagraph view, the comet could be seen on final approach, racing toward perihelion but appearing to fade somewhat in the final stages. Astronomers said comets in such images typically show up as bright pinpoints at the head of the tail, but no such pinpoints were visible in the imagery.

The SDO spacecraft was re-aimed to target the limb of the sun where ISON was expected to pass. But no signs of the comet were immediately seen.