The Cleveland Division

The following is a script from "The Cleveland Division" which originally aired on Jan. 25, 2015, and was rebroadcast on May, 31, 2015. Bill Whitaker is the correspondent.

On Tuesday, the Department of Justice and the Cleveland Division of Police agreed on a plan to reform the city's police force. It's an effort to rein in excessive use of force and repair the damaged relationship between the department and the community it serves. The news comes after a year of crisis for law enforcement in America. The fragile trust between cops and many inner city residents has been broken by the deaths of unarmed black men in encounters with police in Ferguson, New York City, North Charleston, and most recently, Baltimore.

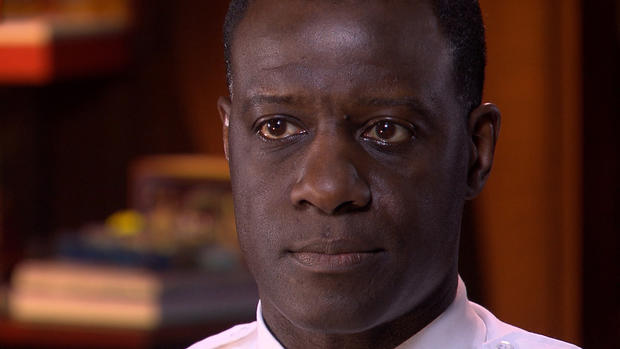

As we first reported in January, tensions reached a critical stage in Cleveland when a city cop killed 12-year-old Tamir Rice as he played in a park with a toy gun. Now it's up to the city's chief of police, Calvin Williams, to calm the outrage and reform a department in one of the most violent cities in America.

Bill Whitaker: Are there bad guys within the police department?

Calvin Williams: Of course there are. And it's my job to make sure we weed out the bad people from this division, and that we nurture and grow and support the good officers that are out there.

Chief Calvin Williams has been a cop in Cleveland for 29 years. He's faced one crisis after another since assuming command last year. No incident in Cleveland has been more horrifying than the killing of Tamir Rice. Security camera video captured Rice playing with a pellet gun. The police pulled up, and within two seconds an officer shot the boy. On the left you see Tamir's 14-year-old sister being tackled by police as she rushed to her dying brother.

"...it's my job to make sure we weed out the bad people from this division, and that we nurture and grow and support the good officers that are out there."

Bill Whitaker: The police ride up. And almost even before the door is open, the 12-year-old boy is shot.

Calvin Williams: A 12-year-old boy lost his life. Period. And what makes it even more difficult for me not just as a person that lives in the city but as a chief is that that happened at the hands of a police officer.

The rookie officer who killed Rice was hired by the Cleveland PD even though another police department had found him emotionally unfit and forced him to resign.

Bill Whitaker: How did he get hired by the Cleveland Police Department?

Calvin Williams: Those are things that are under investigation, that we're definitely taking a second, a third, and a fourth look at.

Bill Whitaker: How did he slip through?

Calvin Williams: We know some of the things that happened in that process and we're-- even at this moment-- changing the way some of that is done.

Prosecutors are investigating the Rice case. Protests against --- and in support of police have continued in Cleveland ever since the shooting.

Bill Whitaker: You've got a predominantly black city, and a majority white police force. Does that need to change?

Calvin Williams: Diversity is always at the forefront of what I'm trying to do in this city. But if you come from the premise that only an African American can police other African Americans, then we're all doomed to failure.

Bill Whitaker: You've heard about, the talk that many African American families have with their young sons to watch out when they have an encounter with the police. Is that unnecessary?

Calvin Williams: Well, Bill, I don't want to minimize that because I know that happens a lot in minority communities. I can say from a personal standpoint, you know, I have a 24-year-old son and I've never had that talk with him. You know, I expect him to be respectful and to act properly no matter who he's encountering, whether it's a police officer or a news anchor person. Is there something that happens in this country between African Americans or minorities and law enforcement? Yes, it does happen.

The city asked the U.S. Justice Department in 2013 to investigate the Cleveland PD after more than 100 police officers joined a high speed chase and fired 137 times at this car, killing two unarmed people inside. Police mistook their car backfire for gun shots.

The Justice Department report found a pattern of "unnecessary and excessive use of deadly force" and it described an "us-against them" mentality between the police and the community. What's more, some suspects were beaten, pepper sprayed, and Tasered even after they were already in custody.

Bill Whitaker: The report found a pattern of excessive use of force. You disagree with that?

Calvin Williams: Yes, I do.

Bill Whitaker: The report found that it was systemic within the division. You disagree with that?

Calvin Williams: Yes, I do.

Bill Whitaker: What do you agree with?

Calvin Williams: I agree that there are some issues within the Cleveland Division of Police as they pertain to use of force, as they pertain to reporting, and community issues. And we are working diligently both with the Department of Justice and with the community to make sure that we correct those things.

There's a memorial here at the spot where 12-year-old Tamir Rice was shot. But this park is hallowed ground for cops too. Less than 100 yards away are memorials to two officers killed on duty. One was murdered by a drug dealer. Another by a rape suspect. When it comes to pain in Cleveland, there isn't much distance between the people and the police.

Six Cleveland cops have been killed in the last 20 years. Danger and stress take their toll --- a police officer's life expectancy here and around the country is 10 years shorter than the average American.

Officers Shane Bauhof and Eric Newton patrol Cleveland's 4th district, the most dangerous beat in the city. They told us about a struggle with a drunk suspect who tried to grab Newton's gun.

Eric Newton: There's safeguards to keep it from just coming out--coming straight out. But, I mean, you can hear that. And I can feel it tugging on my hip.

Bill Whitaker: He's trying to pull it out.

Eric Newton: With both hands.

Bill Whitaker: Were you scared? That had to be frightening.

Eric Newton: It's terrifying. You're keenly aware of what the consequences are if he's successful in doing that.

Bill Whitaker: Does it still haunt you?

Eric Newton: I don't think I'd use the word haunt...I find myself thinking about it now every time I talk to somebody.

They have been partners for six years, and have never wanted to work in any other neighborhood.

Shane Bauhof: I don't live here, but this is my community. A lotta times in a busy week, I spend more time here than with my own family at home. It's not me against them. I'm out here protecting.

The murder rate in Cleveland last year was higher than in Chicago, New York, or Los Angeles. 103 people were killed in Cleveland, 42 in this neighborhood. This day, the wind chill was 20 below zero.

But Newton and Bauhof kept the car window open so they can hear gunfire.

Bill Whitaker: This is the most dangerous area?

Shane Bauhof and Eric Newton: One of...

Shane Bauhof: I can tell you there are some individuals in the community who do scare me a great deal, given the types of things they've done in the past and the arrests we've made involving them. Yeah, they scare me.

Shane Bauhof: If an officer comes out here and says he's not scared of anything, he's a liar.

Bill Whitaker: How do you protect and serve people you're afraid of?

Calvin Williams: You know if you look at things that have happened around the country, both to other people and the police officers, some of that fear is warranted. Because there are people out there that mean harm to police officers.

One of the problems exposed in the Justice Department report was how the Cleveland police improperly deal with the mentally ill. Tanisha Anderson had a history of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Last November, she was disoriented and outside in the cold wearing a nightgown. Her brother, Joell, and her mother, Cassandra, called for an ambulance. Two police officers responded instead.

Joell Anderson: She was treated like a criminal instead of a human being that had a right, you know, to get some help.

The family and the cops agreed that Tanisha needed to go to the hospital. But when police moved to put her in the squad car, her brother saw her panic.

Bill Whitaker: How was she behaving?

Joell Anderson: She was just holding onto the car doors.

Bill Whitaker: Not allowing them to push her in.

Joell Anderson: Right, that's all she was doing, just holding onto the car doors.

Cassandra Johnson: I've never seen so much force from a big hand crunched down on somebody's head like that, just constantly, constantly trying to get her in the car. And I'm like what is going on, is she a criminal or what?

Joell Anderson: The big cop, he slammed my sister.

Bill Whitaker: He slammed her?

Joell Anderson: He slammed her. He snatched her off the car, the inside of the police car--and he slammed her.

Bill Whitaker: And he slammed her to the ground?

Joell Anderson: To the ground. I never will forget that.

Bill Whitaker: The officers say that Tanisha was kicking at them and resisting them.

Joell Anderson: That's absolutely untrue. I was there. I know.

The family says one officer put his knee in her back as he cuffed her face down on the sidewalk. She stopped moving. They waited 20 minutes for an ambulance. She was pronounced dead at the hospital. Tanisha Anderson was 37. The medical examiner ruled her death a homicide. The Anderson family is suing Cleveland and has demanded all officers be trained to deal with the mentally ill.

Calvin Williams: It's another incident that we definitely feel sorry that it happened, period.

Bill Whitaker: Do your officers have training in how to deal with the mentally ill?

Calvin Williams: Yes some of our officers do. We have approximately close to 450 officers that are trained in crisis intervention.

Bill Whitaker: 450 out of how many?

Calvin Williams: Out of approximately 900 that are in patrol. The agencies that were in place, I'd say 10 years ago, to handle things with the families, to handle things with mental illness, to handle things with addiction aren't there anymore. People call 911, we have to respond.

The department received a staggering 400,000 calls for assistance last year --- more than one call per resident. Chief Williams says he wants his officers to stop responding to so many non-emergency calls and instead get out of their squad cars and get to know the community.

But it can be uncomfortable for police, which is exactly what we saw when we asked officers Newton and Bauhof to meet with some of the people they serve at this community center.

Bill Whitaker: What is the perception of the police?

John Eberhart Jr.: In this neighborhood, it's not that good.

Brandon McCruel: Some people get that badge on they chest. And they think they become Superman. They got a right to take on the world.

Bill Whitaker: How do you differentiate these kids from the ones you call the bad guys?

Shane Bauhof: One of the things is probably a smile and a wave and, "How you doin', officer," instead of spittin'.

Bill Whitaker: Why do you think they would spit at you?

Shane Bauhof: Not everyone likes the police.

John Eberhart Jr.: It seems like every time a young, black man is involved, they shoot first, ask questions later.

Shane Bauhof: Me and my partner arrested hundreds of gun arrests. Neither one of us have ever fired our gun at anybody.

Bill Whitaker: Eric, you been kinda quiet here.

Eric Newton: Well, I'm listening.

Bill Whitaker: What are you hearing?

Eric Newton: More communication. I've never encountered a situation that couldn't benefit from more communication.

"It seems like every time a young, black man is involved, they shoot first, ask questions later."

The Justice Department is insisting on reforms including new rules on the use of deadly force and faster ways to discipline bad cops.

Calvin Williams: Unfortunately, it takes time. You know, I for one would love to be able to wave my magic wand and have this change tonight.

After spending four days with Chief Williams, you get the sense that he's disgusted, even furious that the actions of some of his officers have so badly damaged the reputation of the department he's risked his own life for.

Calvin Williams: I had people actually trying to take my life on four separate occasions. And I survived that. I could give you a whole list of officers attacked with deadly weapons that survive and don't end up using deadly force against that person.

Bill Whitaker: What's at stake here for Cleveland?

Calvin Williams: Everything. Everything's at stake. I mean, I talk to people every day that say, "We support you and we know you have a difficult job to do with the division of police. But we know in the end this police department will be better." And if that's not the case at the end of this, then I failed at my job. And I hate to fail.

The investigation into the shooting of 12-year-old Tamir Rice is still not complete -- more than six months after he was killed by a Cleveland cop. The Rice family says the boy's remains still have not been buried because another forensic examination could be necessary.