How much have taxpayers spent to keep Charles Manson in prison?

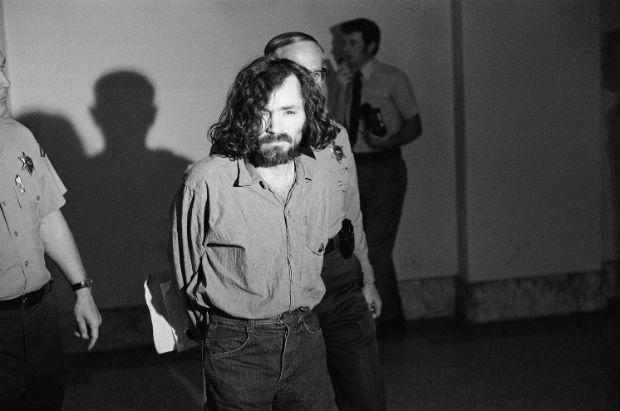

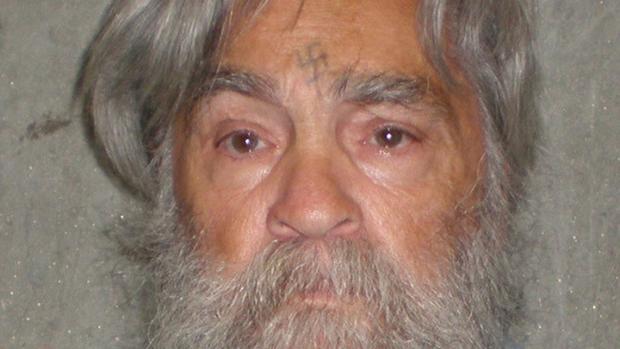

Charles Manson is sick and may be dying. After a trip to the hospital and back to prison, one of America’s most famous murderers may finally be arriving at his end -- nearly 46 years after California had sentenced him to death. Apparently, Manson is too old and sick for any lifesaving surgery.

That means the state’s taxpayers may soon finally stop paying to keep him alive -- a tab that has easily already exceeded $2 million. Of course, owing to the amorphous nature of the actual costs of incarcerating a single prisoner, the total expense California has incurred for Manson may never be accurately tallied.

But the mass murderer, with at least seven killings to his credit, is likely pleased with himself for the ride he has taken the state on by living to the ripe age of 82. To cover his extended stay in prison, California has paid double the amount that it would have cost to execute Manson after his conviction. And his memory will always be with us: His picture -- often smiling if not glaring -- still stalks us from crime magazines on the supermarket shelf.

Manson is one of the most infamous murderers in history because of his role in the Tate-LaBianca slayings on two hot nights in Los Angeles in August 1969. Members of the so-called Manson “family” carried out the rampage Manson planned that took the lives of five people, including pregnant actress Sharon Tate on the first night. Then they bludgeoned and stabbed the LaBianca couple in their home the next night.

Caught, tried and convicted for these murders, Manson was sentenced to death by a California judge and jury in 1971.

But luck was on his side. In 1972 the California Supreme Court outlawed the death penalty. Instead, Manson received seven concurrent life sentences, making him eligible for parole every seven years.

Over the course of time, Manson has had 12 parole hearings, been denied his freedom all 12 times and remains in California state prison. That makes him a prime example of what happens when a murderer -- an obviously guilty one -- is not executed.

Putting aside the morality of capital punishment, there has always been an economic argument against inflicting the death penalty on someone like Manson. Opponents argue that it costs more to kill a criminal than to keep him incarcerated.

While it’s true that the initial costs of a death penalty case are higher, the exact amounts differ from study to study and state to state. An analysis by a bar association in Washington state indicated that the legal and courts costs, including providing at least two attorneys for the defendant and lengthy appeals that could go all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, run to a little more than $1 million. The cost of an execution itself, based on a 2010 case, it adds another $100,000.

But having to keep Manson alive all these years has cost the state of California a good deal more. The annual cost of maintaining a prisoner was an average $39,000 in 2010, according to a Vera Institute of Justice study, when items such as correction officers’ pensions were included. Adding inflation from then to now brings it close to $42,000. And in some states like Illinois and Connecticut, costs run more than 30 percent higher.

So even if Manson had been a routine prisoner, he would have cost California taxpayers nearly $2 million. But during his life in jail, he has been far from a model inmate. Manson has committed more than 100 offenses, including assault, possession of a deadly weapon, trying to intimidate staff and having an illegal cellphone.

Even behind bars he has been described as “the most dangerous man in America,” in one story, “unshackled, unapologetic and unruly” in another. So he required constant watching. In that respect, Manson is similar to other lifers without the prospect of ever being paroled. They have nothing to lose.

How much more does this add to the cost of keeping someone like Manson alive? No one really knows, but convicts on death row, who also have nothing to lose by committing further crimes while incarcerated, cost an average of $90,000 more a year than the average inmate, according to one study.

Manson has lived a long, if not fruitful, life given the average life expectancy for a U.S. male is only 76 years. And in that respect, he’s not a lot different than many death row inmates. In one Florida case that went to the U.S. Supreme Court, an inmate was still waiting for execution after 40 years. The court found that the average time on death row is 13 years, and even then about two-thirds of the capital punishment decisions are reversed.

Manson is fairly typical in that the U.S. prison population is aging, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics. The number of prisoners age 55 or older sentenced to state prison increased four times between 1993 and 2013 and is now 10 percent of the total population.

Aging in prison could prove a lot healthier than being on the street for people like Manson. A John Jay School of Criminal Justice study, which focused only on African Americans, showed that they were likely to live longer in jail than on the outside. And older criminals, like older people, generally cost more in medical treatment.

In addition, here are some other costs to consider:

Recidivism: Will a convicted murderer, either in prison or on parole, continue to commit crimes? Obviously guards and other inmates weren’t safe from Manson even in jail, and Manson himself was assaulted and burned by an inmate who threw paint thinner on him.

And if Manson had been paroled, would people be safe from him? A National Institute of Justice study showed that within five years, about seven in 10 violent offenders were rearrested for a new crime.

Celebrity: Murderers like Manson are able to inspire -- if not directly conspire in -- future crimes. A young Manson himself may have been motivated toward a future life of crime when he took guitar lessons from fellow inmate Alvin “Creepy” Karpis, a member of the Ma Barker gang of the 1930s.

If so, he learned his lessons well, because even while in jail, Manson was able to inspire members of his so-called “family” to make two assassination attempts on then President Gerald Ford.

Manson continues to have a cult following, and his life has led to an opera and a musical called “Assassins” by Academy Award-winning composer Stephen Sondheim. An underground newspaper extolled him as “Man of the Year,” and rock group Marilyn Manson was partially named after him. His fame has spread internationally, and current CBS morning anchor Charlie Rose once won an Emmy for an interview with him.

The courts: Would executing Manson and criminals like him make the courts more efficient? Up to 95 percent of all cases that come before the criminal justice system are plea-bargained down.

But in order to plea bargain, a district attorney or federal prosecutor must have the threat of more severe penalties to get a defendant to plead guilty to murder. The death penalty is the ultimate weapon. While most federal and state officials won’t actually say a trade-off is involved in murder cases, many would rather not have to settle for manslaughter in cases where a 25-year-to-life sentence would be more appropriate.

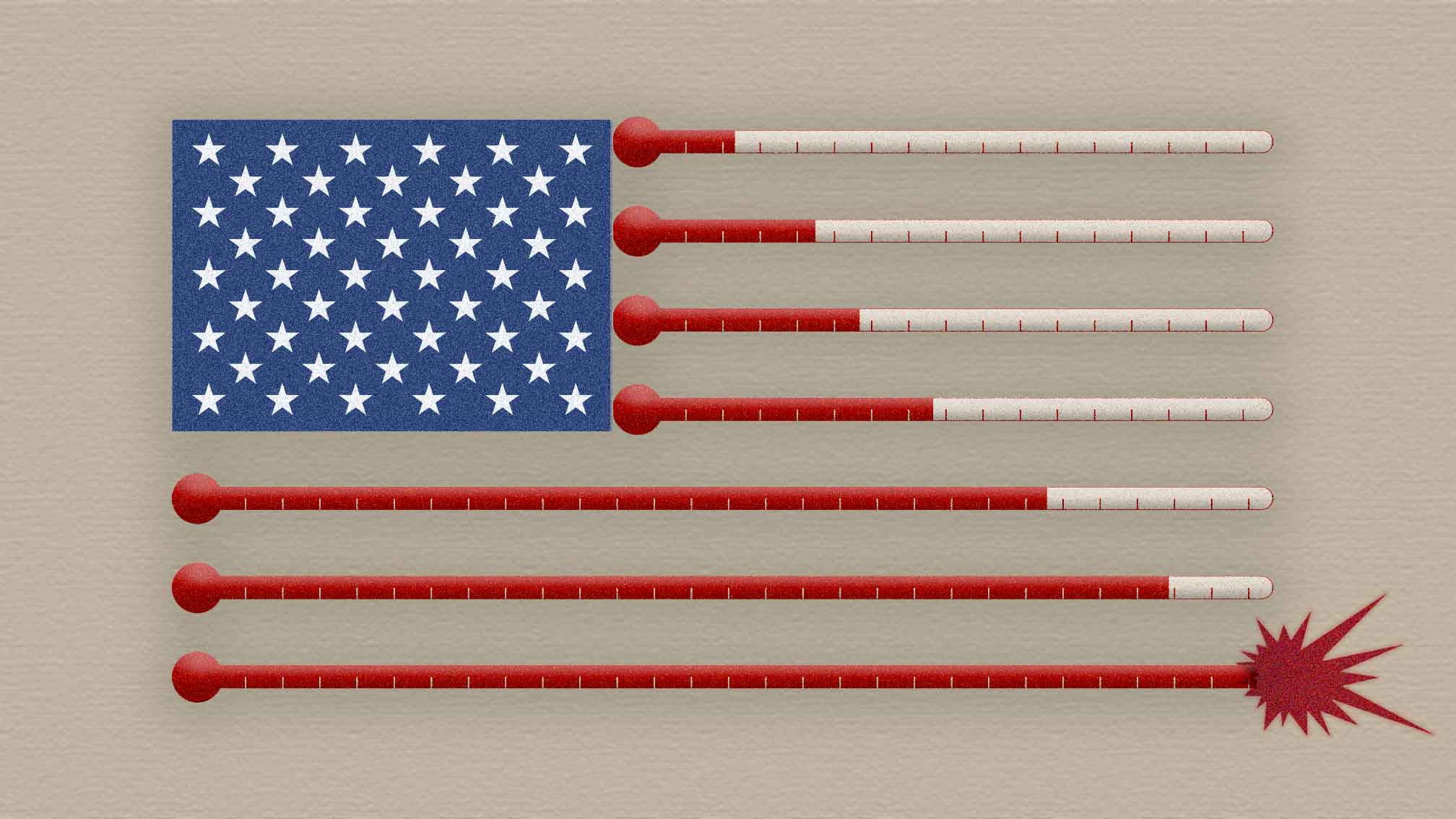

Experienced prosecutors often say the death penalty is no deterrent unless it’s enforced, and in most states, it isn’t. About 2,900 people are currently on death row in 35 states and two federal jurisdictions, but only 20 were executed in 2016 in just five states, with Georgia and Texas having nine and seven, respectively .

This may change. Despite the ongoing moral outcry against the death penalty, liberal California, which leads the nation with 741 inmates on death row, has now reversed direction and approved a referendum to speed executions. Nebraska and Oklahoma voted to retain capital punishment. In South Carolina it’s likely that a jury will impose the death penalty on Dylann Roof for killing nine church members, who died praying for him.

But none of this will affect on Manson. Sooner or later, he’ll peacefully go to his eternal reward, having already had a rich one from taxpayers.