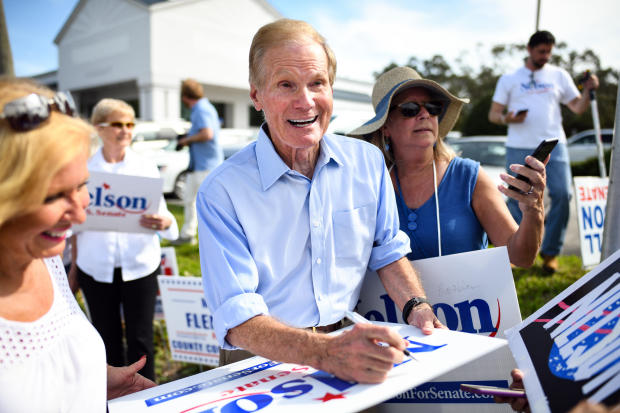

Biden to nominate Bill Nelson, former senator and shuttle veteran, as NASA administrator

Former Democratic Senator Bill Nelson, a longtime space advocate whose district included the Kennedy Space Center and who flew aboard the shuttle Columbia in 1986 as a congressional observer, is President Biden's choice to serve as NASA's next administrator, the White House announced Friday.

If confirmed, he will succeed Jim Bridenstine, who served under the Trump administration and won widespread praise for his tireless efforts to promote the agency's Artemis moon program, aiming to return astronauts to the lunar surface later this decade, and commercial initiatives intended to encourage private-sector space development.

"I am honored to be nominated by Joe Biden and, if confirmed, to help lead NASA into an exciting future of possibilities," Nelson said in a statement. "Its workforce radiates optimism, ingenuity and a can-do spirit. The NASA team continues to achieve the seemingly impossible as we venture into the cosmos."

Nelson would appear to enjoy bipartisan support.

"There has been no greater champion, not just for Florida's space industry, but for the space program as a whole than Bill," Senator Marco Rubio, a Republican from Florida, said in a statement. "His nomination gives me confidence that the Biden administration finally understands the importance of the Artemis program, and the necessity of winning the 21st century space race."

Bridenstine also offered strong support, even though Nelson initially opposed his nomination.

"Bill Nelson is an excellent pick for NASA administrator," Bridenstine said. "He has the political clout to work with President Biden's Office of Management and Budget, National Security Council, Office of Science and Technology Policy and bipartisan Members of the House and Senate.

"He has the diplomatic skills to lead an international coalition sustainably to the Moon and on to Mars. Bill Nelson will have the influence to deliver strong budgets for NASA and, when necessary, he will be able to enlist the help of his friend, President Joe Biden. The Senate should confirm Bill Nelson without delay."

Nelson, 78, served in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1979 to 1991, mounted an unsuccessful run for governor of Florida and then won three terms in the Senate, from 2000 to 2018.

He chaired the Space Subcommittee in the House and served as chairman of the Senate Space and Science Subcommittee, playing major roles in multiple pieces of space-related legislation.

Especially notable to space enthusiasts, on January 12, 1986, Nelson blasted off aboard the shuttle Columbia, becoming the second sitting member of Congress to fly in space after Senator Jake Garn, a Utah Republican.

The pilot of that mission was Charlie Bolden, who would go on to serve as NASA administrator, with Nelson's strong support, under the Obama administration.

While Nelson trained at the Johnson Space Center for his shuttle flight, he was added to the crew as a "payload specialist," a non-professional added to a shuttle crew to operate a specific experiment or to carry out some other role.

In this case, Nelson, like Garn before him, was considered a "congressional observer" thanks to his role on committees that controlled NASA's funding. But he also aided in several medical experiments to learn more about the effects of weightlessness.

Columbia landed in California on January 18, 1986, just 10 days before the Challenger took off on its final mission, which ended in disaster. He later wrote a book about his spaceflight experience titled "Mission: An American Congressman's Voyage to Space."

In 2010, Nelson opposed President Obama's decision to cancel the Bush administration's post-shuttle Constellation moon program and development of heavy lift Ares rockets in favor of a more nebulous asteroid retrieval mission and eventual flights to orbit Mars in the mid 2030s.

The Obama administration did not initially approve development of a new rocket, but Nelson and former Texas Republican Sen. Kay Bailey Hutchinson joined forces to spearhead a successful effort to win White House approval.

"Most every piece of space and science law has had his imprint," the White House said in a statement announcing Nelson's nomination, "including passing the landmark NASA bill of 2010 along with Senator Kay Bailey Hutchinson. That law set NASA on its present dual course of both government and commercial missions."

The heavy-lift rocket Nelson championed evolved into the Space Launch System booster being built today to carry astronauts back to the moon in the Artemis program. Critics dubbed the rocket the "Senate Launch System" because of its political roots.

Nelson's support of the new rocket prompted concern in some quarters that he favored government development at the expense of commercial initiatives.

But the agency encouraged development of private sector rockets and spacecraft to deliver supplies to the International Space Station and awarded contracts worth billions to SpaceX and Boeing to develop and launch capsules to ferry astronauts to and from the lab complex.

Tension between advocates of commercial space enterprise and those supporting more government oversight and control continues with critics of the more traditional Artemis program arguing the private sector could do the job just as safely for less money.

But SLS supporters argue the huge rocket, the most powerful ever built, can launch Orion deep space crew capsules and heavy lunar modules and components in fewer launches using shuttle-heritage propulsion systems with proven reliability.

Now billions over budget and years behind schedule, the SLS rocket is scheduled for its maiden launch on an unpiloted test flight around the moon late this year or early next.

NASA plans to launch a four-member crew in an Orion capsule atop the second SLS rocket in 2023 before an eventual landing near the moon's south pole with the next man and first woman to walk on the surface.

As for the price tag, NASA's inspector general reported last March that total SLS program costs were expected to climb above $18 billion by the time the Artemis 1 rocket finally takes off. Individual, post-development rockets are expected to run between $1 billion and $2 billion each depending on how one does the accounting.

Whether those costs might eventually erode Nelson's support for the huge rocket is not yet known.

In any case, the first stage of the SLS rocket scheduled to fly late this year was successfully test fired Thursday. If no major problems develop, NASA should be ready to launch the SLS on its maiden flight before the end of the year, followed by a piloted test flight in 2023.

While the rocket's first two flights seem assured, Congress has not yet provided the full funding needed for a new moon lander and the Trump administration's 2024 target date for the first astronaut landing is no longer feasible.

The Biden administration has expressed support for the Artemis program in general terms, but it's not yet known what sort of schedule, or how much funding, the administration will support.