Are anti-bullying efforts making it worse?

The month dedicated to the fight against bullying continues, as does the debate over what exactly is the best way to address the issue.

In recent years, parents, educators, researchers and politicians have stepped up the battle against a problem the National Education Association says has reached "epidemic levels."

- Are Anti-Bullying Programs Having An Opposite Effect?

- Stop Your School Bully

- Reevaluating School Bullying

There have been numerous conferences on the issue, including a "Bully Free" summit the NEA hosted Wednesday in Washington.

The growing awareness has been coupled with a growing list of prevention programs at schools across the country, and a growing scrutiny of those programs' effectiveness.

A study published last month in the Journal of Criminology suggested that anti-bullying programs could be having the opposite than intended effects. In an analysis of 7,000 students from 50 states, researchers from the University of Texas at Arlington found that students at schools with anti-bullying initiatives may be more likely to become a victim of bullying.

"This study raises an alarm," the project's lead researcher Seokjin Jeong told CBS Dallas in an interview published Tuesday.

"Usually people expect an anti-bullying program to have some impact -- some positive impact."

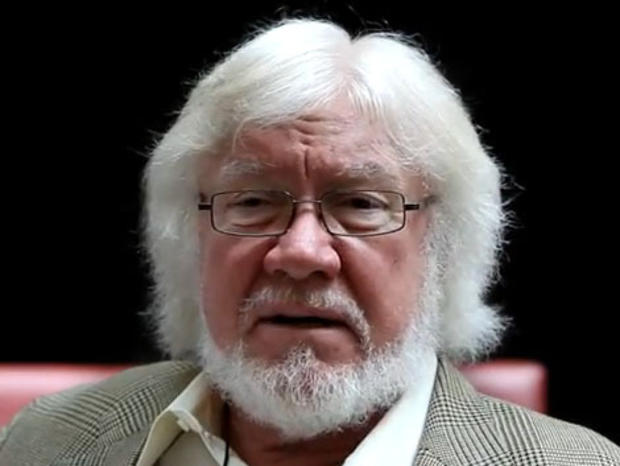

Those findings didn't come as a surprise to Stuart Twemlow, an established voice in the field and co-author of Preventing Bullying and School Violence.

"The doctor's research is completely supported by my experience," said Twemlow, a visiting professor of health sciences at University College, London. "The exact way to make sure that your program is a failure is to target a specific group."

Targeting bullies, is thus, according to Twemlow, a great way to fail at stopping bullying.

In a soon-to-be-published report titled "Rethinking effective bully and violence prevention efforts," Twemlow and his co-authors argue that such targeted bully prevention programs "are, at best, marginally helpful."

These programs fail, the paper argues, for several reasons, including the fact that many programs require resources schools can't afford, that they don't recognize the role of adults in bullying, and that they don't address the school's overall climate.

And, Twemlow and Jeong agree, they may actually give bullies ideas for how to bully more effectively.

"If you have a list that says do this, this and this in case of a bully, the thing you've got to remember is that bullies read them too," Twemlow said.

"Bullies are just as intelligent as other people."

The focus, Twemlow argues, should instead be on comprehensively reforming the school's overall culture.

"Bullies are not the cause of the problem. They're the result of the problem. The problem is in the climate of the school," Twemlow said.

"And when you have a lot of bullies at a school, you have a problem with the leadership of the school. And that's complicated."

The larger bullying prevention field has appeared to shift away from targeting bullies, and bullying behavior, toward improving the overall school climate of the school, as Twemlow advocates.

The NEA condemns zero tolerance policies that target and punish select forms of misbehavior, like bullying. A recent post on the education group's site is titled "Zero tolerance policies earn a big fat 'F.'"

At the same time, the group embraces the concept of improving the quality of character of a school's culture as a tool for preventing bullying.

"A school must do a lot more than put an anti-bullying poster on the front door in order to be bully-free," Joann Sebastian Morris, an NEA senior policy analyst said in a statement.

"Research shows that an entire school's climate must change -- which means changing the norms, values and expectations in a school so that students and staff feel socially, emotionally, and physically safe."

Experts, including Twemlow, warn that increased levels of awareness lead to increased reports of bullying, which can make it seem like the problem is on the rise, or that certain bullying prevention programs aren't working, and that this should be taken into account when assessing studies like Jeong's.

And what about anti-bullying month (or its longer title, Bullying Prevention Awareness Month)?

Twemlow suggests a name change.

"Pro-kindness month. But that would have as much sex-appeal as a dry bone."